The ghost of Seth Brundle looms large, doesn't it? Not just over his ill-fated son, Martin, but over this entire film. Following up David Cronenberg's 1986 body-horror masterpiece, The Fly, was always going to be a Herculean, perhaps even foolhardy, task. How do you replicate that perfect storm of existential dread, tragic romance, and groundbreaking, repulsive practical effects? The Fly II, released onto unsuspecting VHS shelves in 1989, doesn't quite try to replicate it. Instead, it opts for a different, perhaps more conventional, but undeniably gooey path.

### A Different Kind of Buzz

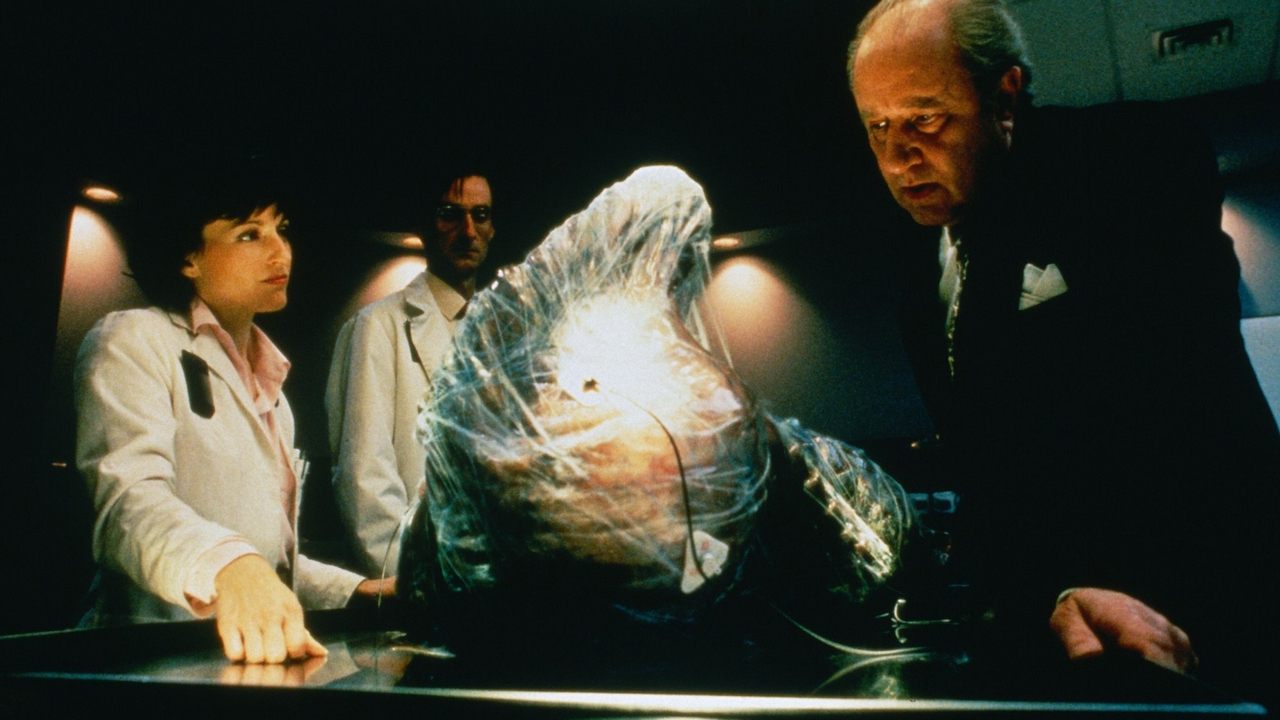

Directed by Chris Walas, the very FX maestro who brought BrundleflyPrime to such unforgettable, dripping life in the original (and netted an Oscar for it), The Fly II shifts the focus. Gone is the slow, Kafkaesque transformation fueled by hubris. Here, we have Martin Brundle (Eric Stoltz, bringing a poignant vulnerability that recalls his work in Mask), the son conceived during Seth's horrific metamorphosis. He's raised in the sterile, menacing confines of Bartok Industries, under the watchful, calculating eye of Anton Bartok (Lee Richardson), the company's ruthless CEO. Martin suffers from Brundle's accelerated growth syndrome, aging years in mere months, a ticking clock strapped to his very DNA. He's a genius, like his father, desperately trying to understand and reverse his inherited condition before his own inevitable, gruesome transformation begins. It’s less a meditation on identity loss, more a race-against-time creature feature with a corporate conspiracy B-plot.

The atmosphere shifts accordingly. While Cronenberg's film felt claustrophobic and personal, trapped in Seth's increasingly grim loft, Walas leans into the cold, blue-steel aesthetic of late-80s sci-fi thrillers. Bartok Industries, with its endless corridors, humming computers, and morally bankrupt scientists, feels like a character in itself – a heartless machine chewing up Martin's childhood and future. It lacks the profound philosophical horror of the original, but generates its own kind of dread – the helplessness of being a pawn in a powerful, uncaring system.

### Where the Slime Mold Grows

Let's be honest, though. Many of us renting this back in the day weren't primarily seeking deep philosophical insights. We came for the splatter, the creature, the effects. And in this arena, Chris Walas, now in the director's chair, delivers with unrestrained, visceral glee. Having literally written the book (or sculpted the latex) on Brundlefly, Walas clearly relished the chance to push the envelope further, unburdened by Cronenberg's more cerebral approach. The transformation sequences here are arguably even more graphic, more drawn-out, and certainly more… liquidy than the first film. Remember Martin's final, agonizing metamorphosis inside that cocoon? It’s a symphony of ripping flesh, cracking bone, and translucent slime that likely had more than a few VCRs put on pause for a collective gasp (or dry heave).

Eric Stoltz reportedly had a miserable time filming, particularly with the extensive and uncomfortable makeup required for the later stages. You can almost feel his discomfort translating into Martin's pained ordeal on screen. His performance, alongside Daphne Zuniga as Beth Logan, a sympathetic Bartok employee who becomes Martin's ally and love interest, grounds the film emotionally. Zuniga, familiar from Mel Brooks' Spaceballs (1987), provides the necessary human connection amidst the escalating body horror and corporate villainy. Their budding romance feels a touch rushed, perhaps a casualty of a script credited to four writers (Mick Garris, Frank Darabont, Jim Wheat, Ken Wheat), but their chemistry provides a necessary counterpoint to the grim proceedings. It's fascinating to see future heavyweight Frank Darabont's name attached here, years before The Shawshank Redemption (1994) would redefine his career.

### The Martinfly Legacy

While the creature design for the 'Martinfly' is impressive – a towering, insectoid monstrosity distinct from its 'father' – it lacks the tragic pathos of Brundlefly. Seth Brundle’s transformation was horrifying because we saw the man disintegrate; Martinfly is presented more as a rampaging monster seeking vengeance, closer to traditional creature features. It’s undeniably effective on that level, leading to a climax filled with satisfyingly gory comeuppance for the villains. The practical effects, while perhaps showing their latex seams a bit more obviously today than Jeff Goldblum's Oscar-winning makeup, still possess a tangible, stomach-churning quality that modern CGI often struggles to replicate. This film feels wet, sticky, and uncomfortable in a way that stays with you.

The production wasn't without its challenges. Reports suggest the film needed trims to avoid an X rating from the MPAA, a common battle for graphic horror films of the era. While its $6.5 million budget yielded a decent $38.9 million box office return (roughly $90 million today), it paled in comparison to the original's impact and profitability. It didn't redefine the genre or spawn legions of imitators like its predecessor.

Yet, The Fly II holds a special place for many VHS hunters. It represents a specific brand of late-80s studio horror sequel: bigger, louder, gorier, but perhaps less thoughtful. It delivered exactly what the lurid poster art and buzzing tagline ("Like father, like son.") promised: a creature feature drenched in slime and spectacle. It’s a film less concerned with asking "What does it mean to be human?" and more focused on showing, in graphic detail, what happens when humanity is violently stripped away.

***

VHS Heaven Rating: 6/10

Justification: The Fly II inevitably suffers in comparison to Cronenberg's towering original. The script feels more conventional, the themes less profound, and the central romance less developed. However, judged on its own terms as a late-80s creature feature, it succeeds thanks to Chris Walas's go-for-broke practical effects, Eric Stoltz's sympathetic lead performance, and a satisfyingly nasty payoff. It delivers the gore and monster action that fans of the era craved, even if it lacks the original's soul.

Final Thought: While it never quite escapes its progenitor's shadow, The Fly II remains a fascinating, often repulsive, and entirely memorable slice of late-80s studio horror – a gooey testament to the era of practical effects supremacy, best appreciated late at night with the lights dimmed low.