The greasepaint grin stretches impossibly wide in the flickering porch light. It’s not funny. It’s never been funny. Clownhouse understands this deep down in its low-budget bones, tapping into that primal, childhood unease many of us buried – the suspicion that beneath the colourful costume and painted smile lurks something hollow, something predatory. Released in 1990, this film arrived just as the 80s slasher boom was winding down, offering a more stripped-back, almost intimate kind of terror. It’s a film that, even before you know anything else about it, feels… wrong.

### Home Alone, But Not For Laughs

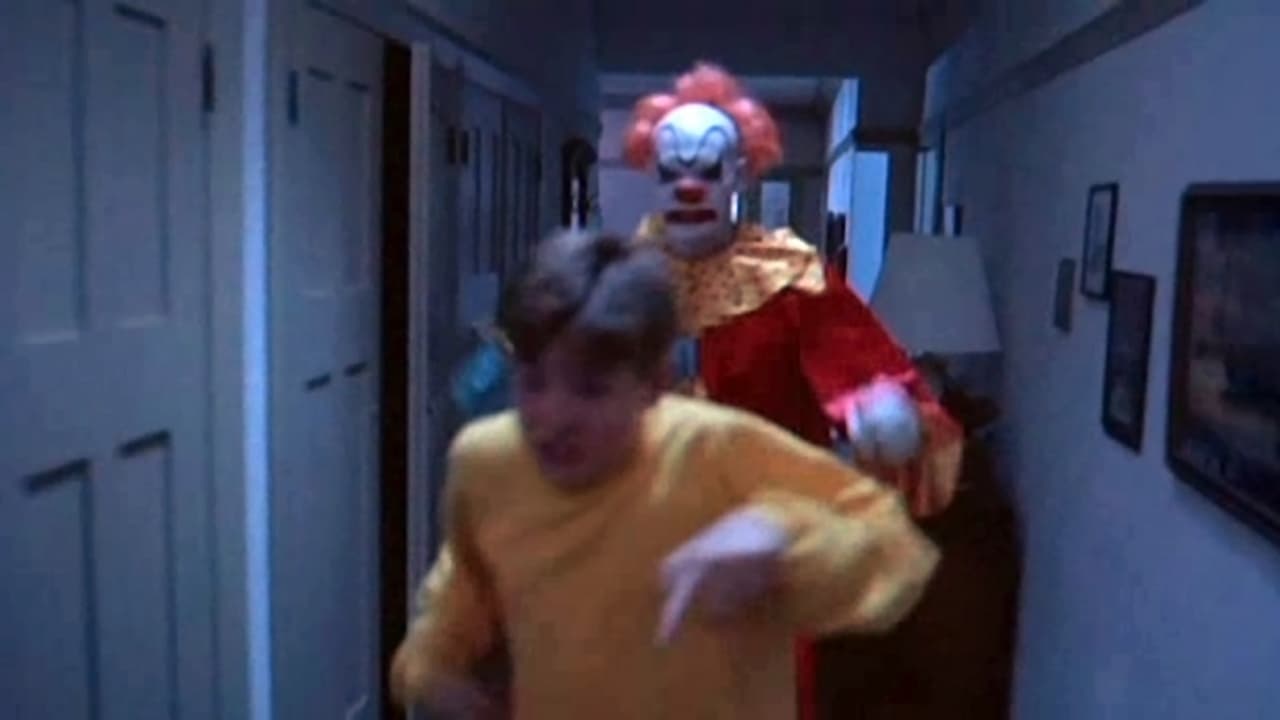

The premise is brutally simple, recalling countless campfire tales and urban legends whispered after dark. Three brothers – Casey (Nathan Forrest Winters), Geoffrey (Brian McHugh), and the eldest, Randy (a pre-stardom Sam Rockwell) – are left home alone one stormy night. Casey, the youngest, already suffers from intense coulrophobia (fear of clowns), a vulnerability the film exploits relentlessly. Meanwhile, miles away, three inmates escape from the local psychiatric hospital, murder a trio of circus clowns, and steal their identities. Their destination? You guessed it. There’s an unnerving directness to the setup, a feeling of inevitable collision that director Victor Salva (Jeepers Creepers) uses to build a surprisingly effective sense of dread, especially in the first half. Shot on a shoestring budget (reportedly around $225,000), the film leans heavily on atmosphere over elaborate gore, turning the familiar childhood sanctuary of home into a shadowy playground for monsters.

### The Unsmiling Faces

What makes Clownhouse work, particularly in its initial stretches, is its understanding of suggestion. The clowns themselves aren't supernatural demons or wise-cracking killers like Pennywise or Freddy. They are silent, almost blank figures defined only by their stolen costumes and murderous intent. Their threat feels chillingly grounded, amplified by the brothers' isolation. The film plays effectively with point-of-view, often aligning us with young Casey, making his fear palpable. Nathan Forrest Winters carries much of the film's emotional weight, portraying Casey's terror with a raw conviction that feels genuine. Seeing a young Sam Rockwell, even in this early role, brings a jolt of recognition; he already possesses that slightly edgy, unpredictable energy that would define his later career, playing the skeptical older brother who initially dismisses Casey's fears. The constraints of the budget are evident – the action is largely confined to the house, the effects are minimal – but Salva uses these limitations to foster a claustrophobic tension. The dimly lit rooms, the rattling windows, the shadows that seem just a bit too deep... it all contributes to a feeling of being trapped alongside the boys. Remember how effective simple, well-timed jump scares felt back then, especially watched late at night on a fuzzy CRT? Clownhouse has a few moments that nail that feeling.

### The Unspeakable Shadow

It is impossible, however, to discuss Clownhouse without confronting the horrific reality that occurred off-screen. Director Victor Salva was convicted of sexually abusing the film's young star, Nathan Forrest Winters, during production. This appalling crime casts an inescapable, deeply disturbing pall over the entire film. Knowing this context transforms the viewing experience from unsettling horror into something profoundly uncomfortable and morally compromised. Scenes depicting Casey's vulnerability, his fear, his pursuit by adult figures disguised in costumes meant to entertain children – they all take on a sickening resonance. The film's themes of hidden danger and predatory threats lurking beneath benign facades become hideously mirrored by the real-life actions of its creator.

This isn't just a "dark legend" or behind-the-scenes trivia; it's a monstrous truth that fundamentally taints the work. It’s a fact that led distributor Francis Ford Coppola (who had initially championed Salva) to publicly distance himself and urge people not to see Salva's later films. The film even received a Grand Jury Prize nomination at the Sundance Film Festival before Salva's crimes came fully to light, a detail that now feels incredibly grim. Does this knowledge completely negate any merit the film might have possessed on its own terms? For many viewers, myself included, the answer is likely yes. The unease the film generates feels irrevocably tied to real-world exploitation, making it incredibly difficult to engage with purely as a piece of genre filmmaking.

### Legacy in Darkness

Stripped of its horrifying context (an impossible task, really), Clownhouse could be remembered as a minor but effective late-era stalk-and-slash entry, notable for its atmospheric tension, reliance on primal fear, and an early Sam Rockwell performance. It successfully weaponizes coulrophobia long before it became a more common trope. But the shadow of its director's crimes is too vast, too dark. It turns the film into a grim artifact, a chilling example of how real-life horror can eclipse manufactured scares. Watching it today doesn't feel like indulging in retro horror fun; it feels queasy, burdened by a weight that no amount of nostalgic fondness for the VHS era can lift. It's a tape that sits heavy on the shelf, a reminder that sometimes the monsters aren't just on the screen.

Rating: 3/10

The rating reflects the film's technical competence in generating suspense and atmosphere, particularly given its budget, and the effectiveness of its core concept. However, the unavoidable and sickening real-life context surrounding its creation drastically undermines any potential enjoyment or recommendation, making it a deeply problematic piece that many will understandably choose to avoid entirely.

Final Thought: Some VHS tapes hold cherished memories; Clownhouse carries a chilling burden, a stark reminder of the darkness that can hide behind even the brightest greasepaint smile.