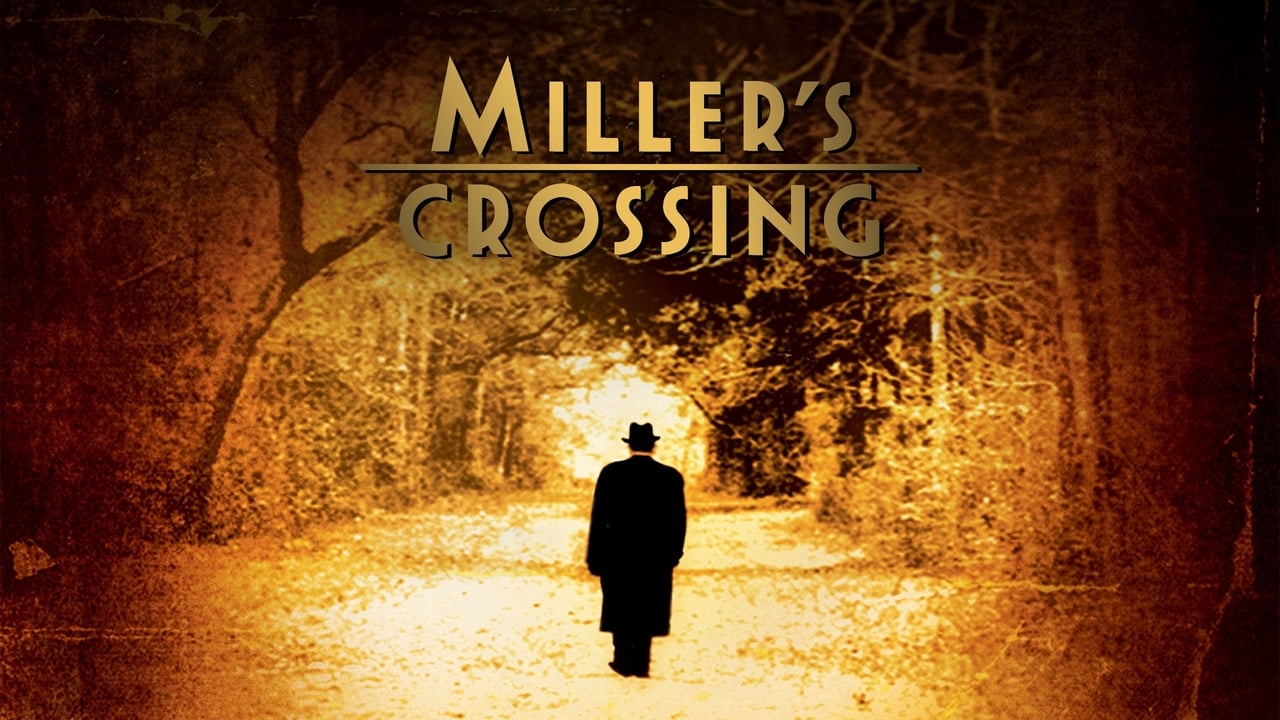

A fedora tumbles through a sun-dappled forest, caught in slow motion, an object imbued with more significance than perhaps any hat has a right to possess. This recurring image from Joel and Ethan Coen's 1990 masterpiece, Miller's Crossing, isn't just a visual motif; it feels like the key to unlocking the film's dense, morally ambiguous heart. Watching it again, decades after first sliding that chunky VHS tape into the VCR, the film feels less like a straightforward gangster narrative and more like sinking into a rich, complex novel – one penned by Dashiell Hammett, perhaps, whose spirit looms large over this Prohibition-era tale.

Into the Labyrinth

The Coens, already known for the neo-noir of Blood Simple. (1984) and the manic comedy of Raising Arizona (1987), didn't just make a gangster film here; they crafted an intricate puzzle box operating entirely by its own internal logic. Set in an unnamed Eastern city (beautifully realized using New Orleans locations), the plot revolves around Tom Reagan (Gabriel Byrne), the melancholic, razor-sharp advisor to Irish mob boss Leo O'Bannon (Albert Finney). When Leo refuses to give up the slippery bookie Bernie Bernbaum (John Turturro) to appease rival Italian boss Johnny Caspar (Jon Polito), Tom finds himself navigating a treacherous path between warring factions, shifting loyalties, and the enigmatic Verna Bernbaum (Marcia Gay Harden), sister to Bernie and lover to both Leo and, secretly, Tom himself. It’s a setup thick with potential betrayals, demanding your full attention from the opening frame. Forget passive viewing; Miller's Crossing insists you lean in, listen closely to the rapid-fire, stylized dialogue, and piece together the allegiances yourself.

A World Drenched in Whiskey and Weariness

What strikes you immediately is the film's stunning visual texture. This was cinematographer Barry Sonnenfeld's final collaboration with the Coens before launching his own directing career with hits like The Addams Family (1991) and Men in Black (1997), and he went out on a high note. The film possesses a burnished, autumnal glow – rich browns, deep greens, shadows that seem to hold secrets. Every frame feels meticulously composed, from the wood-paneled backrooms where deals are struck to the lonely woods that give the film its name. The production design and costuming aren't just period dressing; they create a tangible world, one where honor is a tailored suit and betrayal lurks beneath a perfectly tilted fedora. You can almost smell the stale cigar smoke and cheap whiskey.

The Man Under the Hat

At the center of it all is Gabriel Byrne's Tom Reagan. It's a performance of profound stillness and weary intelligence. Tom rarely raises his voice, his face often an inscrutable mask, yet Byrne conveys volumes through subtle glances and world-weary sighs. He’s the smartest guy in every room, playing angles nobody else sees, but is he principled? Loyal? Or just desperately trying to survive? The film deliberately keeps us guessing. Byrne makes Tom’s exhaustion palpable; he’s tired of the scheming, tired of the violence, perhaps even tired of himself. His constant fiddling with his hat becomes a fascinating character tic – is it a shield, a source of comfort, or just something to hold onto in a world spinning out of control?

Faces in the Shadows

The supporting cast is uniformly brilliant. Albert Finney, who stepped in after the tragic death of Trey Wilson shortly before filming, exudes paternal authority and dangerous sentimentality as Leo. His operatic defence of his home, set to the strains of the Irish folk song "Danny Boy," is an unforgettable sequence, blending brutal violence with unexpected grace. Marcia Gay Harden, in a star-making turn, gives Verna a captivating blend of vulnerability and steely resolve. Is she a femme fatale, a victim, or something far more complex? Like Tom, her motives remain tantalizingly opaque.

And then there's John Turturro as Bernie Bernbaum. Written specifically for him by the Coens (a collaboration that would continue through films like Barton Fink and The Big Lebowski), Bernie is a creature of pure, sniveling self-interest, manipulative and pathetic in equal measure. His desperate plea in the woods – "Look into your heart!" – has become iconic, a moment of excruciating tension and dark comedy that perfectly encapsulates the film's unique tone. It’s a performance that crawls under your skin and stays there.

More Than Just Tough Talk

The Coens famously drew inspiration from Hammett's novels, particularly Red Harvest and The Glass Key, evident in the labyrinthine plot and the hardboiled, almost poetic dialogue. Reportedly hitting a patch of writer's block during the script phase, they took a break to write Barton Fink (1991) before returning to finish Miller's Crossing. That density pays off; this is a film that rewards repeat viewings, revealing new layers of meaning and subtle connections each time. The slang ("What's the rumpus?", "giving someone the high hat") feels authentic yet heightened, creating a linguistic world as distinct as the visual one.

Despite its critical acclaim for style and intelligence, Miller's Crossing wasn't a box office smash initially, earning back only about $5 million of its estimated $10-14 million budget in the US. Like many classics of the VHS era, its reputation grew steadily through rentals and word-of-mouth, cementing its status as a cornerstone of the Coen Brothers' formidable filmography and a high point of 90s neo-noir. Watching it on a CRT back in the day, the slightly softer image perhaps even enhanced its dreamy, almost mythical quality.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's masterful craftsmanship, its complex narrative, unforgettable performances, and enduring atmosphere. It's a demanding film, yes – its intricacies and moral ambiguities might frustrate those seeking simple resolutions – but the intellectual and aesthetic rewards are immense. It doesn’t just depict a gangster world; it creates a complete, self-contained universe governed by its own codes and consequences.

Miller's Crossing lingers long after the credits roll, leaving you pondering the nature of loyalty, the price of survival, and just what exactly Tom Reagan keeps under that ever-present hat. It’s a film that gets better with age, a true gem from the golden age of video stores.