Okay, settle in, maybe pour yourself something comforting – because the film we're revisiting today offers anything but. Venice, in Paul Schrader's suffocatingly beautiful The Comfort of Strangers (1990), isn't just a city of canals and fading grandeur; it's a shimmering, humid labyrinth where desire curdles into something deeply unsettling, a gilded cage slowly closing around unsuspecting prey. Watching it again now, years after first encountering its unsettling power on a worn VHS tape rented perhaps on a whim, that sense of quiet dread feels just as potent, maybe even more so.

A Holiday Adrift

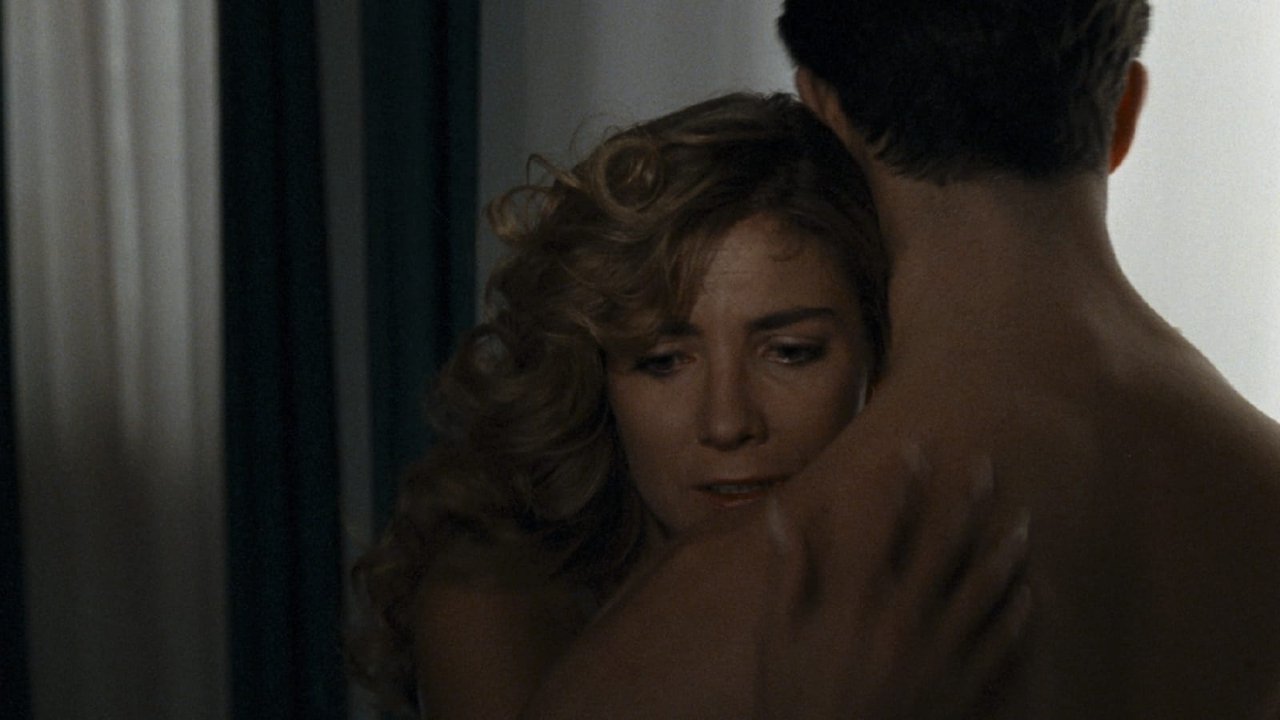

We meet Colin (Rupert Everett) and Mary (Natasha Richardson) as they navigate the city, ostensibly on holiday to rekindle a flame that seems to have dwindled to embers. They wander, beautifully framed by Dante Spinotti’s gorgeous, almost painterly cinematography (which deservedly won him accolades), yet they seem disconnected – from Venice, from each other. Their conversations drift, intimacy feels strained. Richardson, always an actress of remarkable transparency, perfectly captures Mary’s underlying unease and longing, while Everett embodies Colin's slightly passive, perhaps self-absorbed nature. They are adrift, making them vulnerable targets for the strange currents swirling around them. I remember seeing Natasha Richardson here, so full of life and subtle emotional shading, and it adds another layer of poignancy watching it now.

The Seductive Serpent

And then, he appears. Robert, played by Christopher Walken in a performance that weaponizes his unique brand of hypnotic charm and off-kilter menace. He finds them lost, offers help, wine, stories. Walken is magnetic, his tailored white suit gleaming against the Venetian decay, his monologues rambling yet strangely compelling. He speaks of his powerful father, his peculiar upbringing, his relationship with his wife, Caroline. There's an immediate sense that something is off, but his sheer presence, his confidence, is disarming. He’s the spider inviting the flies into his parlour, and Walken makes you understand, chillingly, why they might just accept. It's a performance built on subtle shifts, where politeness feels like a veiled threat, and warmth carries an icy undercurrent.

An Invitation to the Palazzo

The invitation to Robert and Caroline’s opulent, almost museum-like apartment deepens the spell. Here we meet Caroline, portrayed with unnerving stillness and calculating vulnerability by Helen Mirren. The dynamic between Robert and Caroline is the dark heart of the film. She seems subservient, almost broken, yet possesses a quiet strength and complicity that is deeply disturbing. Mirren delivers her lines with a precision that hints at buried trauma and carefully constructed facades. The couple’s stories about their past, their desires, their strange games become increasingly personal and invasive, yet Colin and Mary remain, trapped by a combination of politeness, fascination, and perhaps a subconscious attraction to the danger they sense. This wasn't the kind of film you just stumbled upon easily at Blockbuster; finding it felt like unearthing something potent, maybe even a little forbidden, tucked away in the drama section.

Schrader, Pinter, and the Art of Unease

Paul Schrader, a director never shy about exploring the darker corridors of the human psyche (think his script for Taxi Driver (1976) or his direction on American Gigolo (1980)), works wonders here with the screenplay adapted by the legendary playwright Harold Pinter from Ian McEwan's sharp, unsettling novella. Pinter's famous pauses, the silences laden with unspoken meaning, are perfectly suited to the material. The dialogue often feels like a carefully choreographed dance around uncomfortable truths. Schrader masterfully uses the claustrophobic beauty of Venice, turning picturesque canals and shadowy alleyways into disorienting traps. The elegance is suffocating. Adding immeasurably to this atmosphere is the score by Angelo Badalamenti, fresh off his iconic work on Twin Peaks. His music here is less overtly dramatic, more of a pervasive, dreamlike hum that underscores the mounting dread. Schrader and Badalamenti had previously collaborated on Patty Hearst (1988), and their synergy here creates a truly immersive, if deeply uncomfortable, experience. The film itself wasn't a commercial success – made for around $5 million, it barely scraped back $3 million at the box office – perhaps its challenging, arthouse nature and deliberate pacing kept mainstream audiences away, cementing its status as more of a cult discovery.

Performances That Linger

While Walken’s Robert is perhaps the most overtly striking character, the entire quartet delivers exceptional work. Everett and Richardson capture the subtle erosion of their characters’ connection, their passivity making the eventual horror all the more chilling. And Mirren... her performance is a masterclass in controlled intensity. A scene where she reveals a deeply personal, disturbing memory is simply unforgettable, delivered with a quiet devastation that stays with you long after the credits roll. The collaboration between these four actors, under Schrader’s controlled direction and speaking Pinter’s precise words, creates a potent cocktail of psychological tension. Apparently, Pinter’s uniquely rhythmic dialogue and signature pauses proved a challenge even for seasoned actors like Walken, demanding absolute precision – a precision that translates into palpable on-screen tension. Both Pinter (for his screenplay) and Spinotti (for cinematography) picked up Evening Standard British Film Awards for their outstanding work here, a testament to the film's artistic calibre.

Reflections in a Murky Canal

The Comfort of Strangers isn't an easy watch. It’s slow, deliberate, and ultimately quite shocking. It explores uncomfortable themes about power dynamics in relationships, the allure of the forbidden, the darkness that can hide beneath beautiful surfaces, and the horrifying consequences of emotional passivity. What does it say about Colin and Mary that they allow themselves to be drawn so deeply into this strange couple's orbit? Is there a part of them, however small, that desires this transgression? The film doesn't offer easy answers, leaving the viewer to grapple with the unsettling ambiguity. It forces us to confront the 'comfort' we sometimes seek in the unfamiliar, and the potential dangers lurking within that embrace.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional craft, haunting atmosphere, and powerhouse performances, particularly from Walken and Mirren. The direction, writing, cinematography, and score work in perfect, unsettling harmony. It loses a couple of points simply because its deliberate pacing and disturbing subject matter won't resonate with everyone; it demands patience and a willingness to be made uncomfortable. However, for those seeking a mature, psychologically complex thriller that prioritizes mood and character over cheap thrills, it’s a standout from the era.

It’s a film that burrows under your skin, less interested in jump scares and more focused on a creeping, existential dread. The Comfort of Strangers remains a chilling reminder that sometimes the most dangerous threats are the ones we willingly invite into our lives, seduced by a veneer of sophistication and charm. What truly lingers is the echo of Pinter's silences, filled with unspoken horrors.