What happens when the ordinary rhythms of suburban life are disrupted not by a bang, but by a whisper – a rumor wrapped in silence? Hal Hartley's 1989 debut, The Unbelievable Truth, doesn't announce itself with fanfare. Instead, it drifts into view with a peculiar, deadpan grace, immediately setting a tone that feels both familiar in its late-80s Long Island setting and utterly distinct in its cinematic language. It forces us to lean in, to listen closely to the pregnant pauses and carefully constructed sentences, wondering what seismic truths might lie beneath the placid surface.

Suburban Stillness, Unspoken Secrets

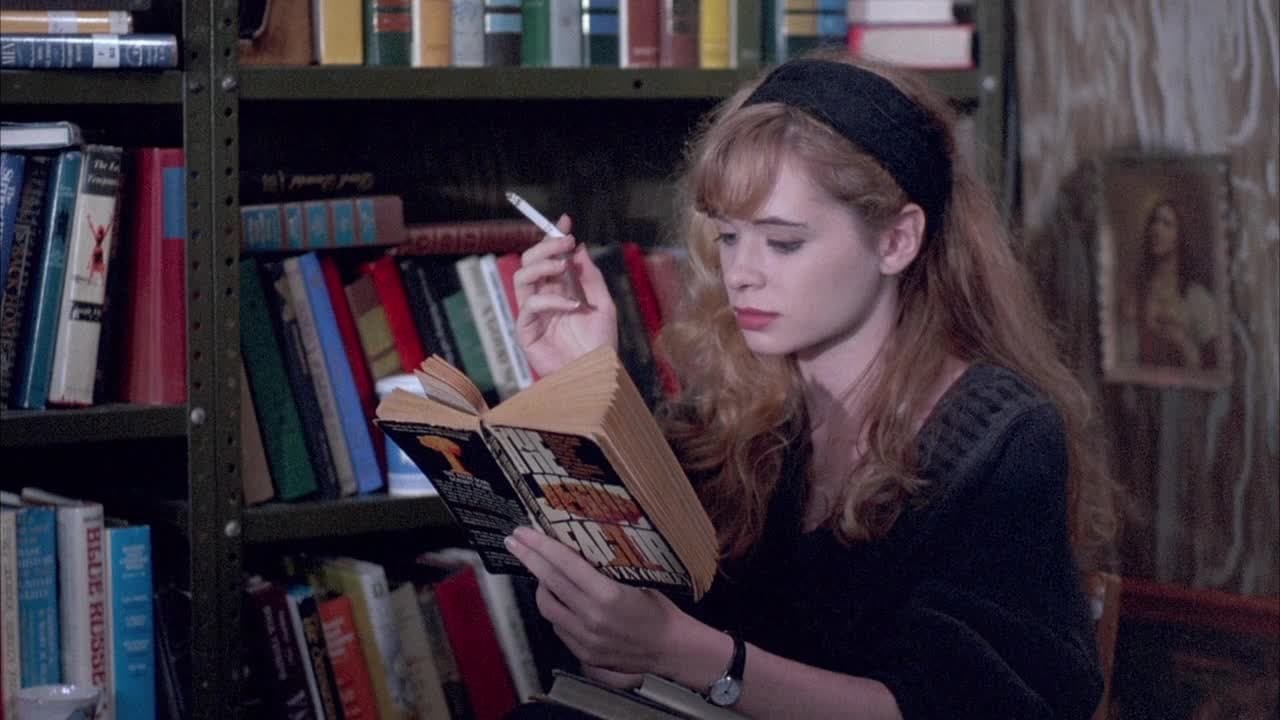

The film centers on Audry Hugo (Adrienne Shelly), a high school senior preoccupied with the threat of nuclear annihilation and disillusioned with the path laid out for her – college, conformity. She defers her Harvard acceptance, deciding instead to become a model, much to the pragmatic chagrin of her father, Vic (Christopher Cooke), a perpetually stressed auto mechanic. Into this precisely drawn world walks Josh Hutton (Robert John Burke), fresh from a prison sentence for a vaguely alluded-to manslaughter (or was it murder?). He's quiet, polite, mechanically gifted, and carries the weight of his past like an invisible shroud. Naturally, he gets a job working for Vic, and just as naturally, Audry finds herself inexplicably drawn to him.

Hartley establishes his signature style immediately. The compositions are often formal, almost painterly, trapping characters within the frame of suburban architecture. Dialogue isn't just spoken; it's delivered with a rhythmic precision, often feeling less like natural conversation and more like philosophical pronouncements filtered through everyday anxieties. It’s a style that could easily feel alienating, yet here, it works beautifully to underscore the characters' own sense of detachment and the underlying absurdity of their situations. How else to react to Audry’s earnest, slightly awkward modeling poses, or the way characters discuss profound life choices with the same flat affect they use to order coffee?

Truth in Performance

The casting feels like lightning in a bottle. This was Adrienne Shelly's breakout role, and it’s impossible to imagine anyone else embodying Audry’s unique blend of intellectual curiosity, youthful idealism, and world-weary cynicism. She possesses a captivating presence, conveying deep thought and vulnerability even through Hartley's stylized constraints. Her performance feels incredibly authentic, capturing that specific feeling of being young, smart, and utterly adrift in a world that doesn’t seem to make sense. Discovering later that Shelly was working as a waitress when Hartley cast her only adds to the magic – a star waiting for the right, slightly off-kilter spotlight.

Robert John Burke, too, is perfect as Josh. His stoicism isn't emptiness; it's a carefully constructed defense mechanism. There's a constant flicker of turmoil beneath the surface, the quiet burden of a past that defines him in the eyes of the town, regardless of the actual "unbelievable truth." Burke handles the ambiguity masterfully, making Josh both enigmatic and deeply sympathetic. And Christopher Cooke as Vic provides a crucial anchor, his gruff pragmatism and simmering frustration offering both comic relief and a relatable portrait of blue-collar worry. His interactions with Josh, particularly their shared language of engines and repairs, form some of the film’s most quietly resonant moments.

Behind the Indie Curtain

Knowing The Unbelievable Truth was Hal Hartley's feature debut, shot for a reported shoestring budget (figures range from $75,000 to $200,000, peanuts even then!) over a mere 11 days in his hometown of Lindenhurst, Long Island, adds another layer of appreciation. This wasn't just a movie; it was a declaration of artistic intent. You can feel the resourcefulness, the commitment to a singular vision that would define Hartley's subsequent work like Trust (1990) and Simple Men (1992). The film’s title itself, evoking the sensationalism of tabloid headlines, perfectly mirrors the central theme: how easily perception hardens into accepted fact, especially in the echo chamber of a small town. It’s a testament to the script and performances that such complex ideas land with precision within this minimalist framework. The positive reception at festivals like Sundance wasn't just luck; it was recognition of a fresh, intelligent voice emerging in American independent film.

Lingering Questions Under a Muted Sky

What does The Unbelievable Truth leave us with? It’s not a film offering easy answers or neat resolutions. Instead, it lingers like a half-remembered conversation, prompting reflection on the nature of truth itself. Is truth objective, or is it shaped by gossip, fear, and the stories we tell ourselves? How do past actions ripple outwards, defining futures in ways we can't always control? The film explores these weighty themes with a surprisingly light touch, finding dark humor and profound humanity in the mundane struggles of its characters. Its deliberate pacing and stylized dialogue might be an acquired taste for some, demanding patience, but the reward is a uniquely atmospheric and thought-provoking piece of late 80s indie filmmaking. Doesn't Audry's quiet rebellion against expectation still resonate today?

Rating Justification: 8/10

The Unbelievable Truth earns a strong 8 out of 10. Its score reflects its significance as a highly influential debut that established Hal Hartley's unique voice and launched the career of the luminous Adrienne Shelly. The film's strength lies in its distinctive deadpan style, intelligent script exploring complex themes with subtlety, and perfectly pitched performances that find emotional depth within stylized constraints. The low-budget ingenuity and palpable sense of place further enhance its charm. While its deliberate pacing and anti-naturalistic dialogue might not appeal to all tastes, preventing a higher score, its artistic confidence and lasting resonance as a key work of American independent cinema make it a must-see for enthusiasts of the era.

This isn't just a film; it's a mood piece, a philosophical inquiry disguised as a suburban dramedy. It captures that specific late-80s indie spirit – smart, slightly melancholy, and utterly original. It’s a quiet film that speaks volumes, leaving you pondering the elusive nature of truth long after the credits, and maybe the VCR, have stopped rolling.