How does a filmmaker say goodbye? For Agnès Varda, the perpetually curious, endlessly inventive godmother of the French New Wave, the answer was to turn her camera towards the beginning. Jacquot de Nantes (1991) isn't just a biographical film; it's an act of profound love, a tender reconstruction of her husband Jacques Demy's childhood, filmed as Demy himself was fading away. It’s a film that arrived on shelves perhaps quieter than the action flicks or comedies of the era, but its resonance lingers far longer than most.

Capturing the Spark

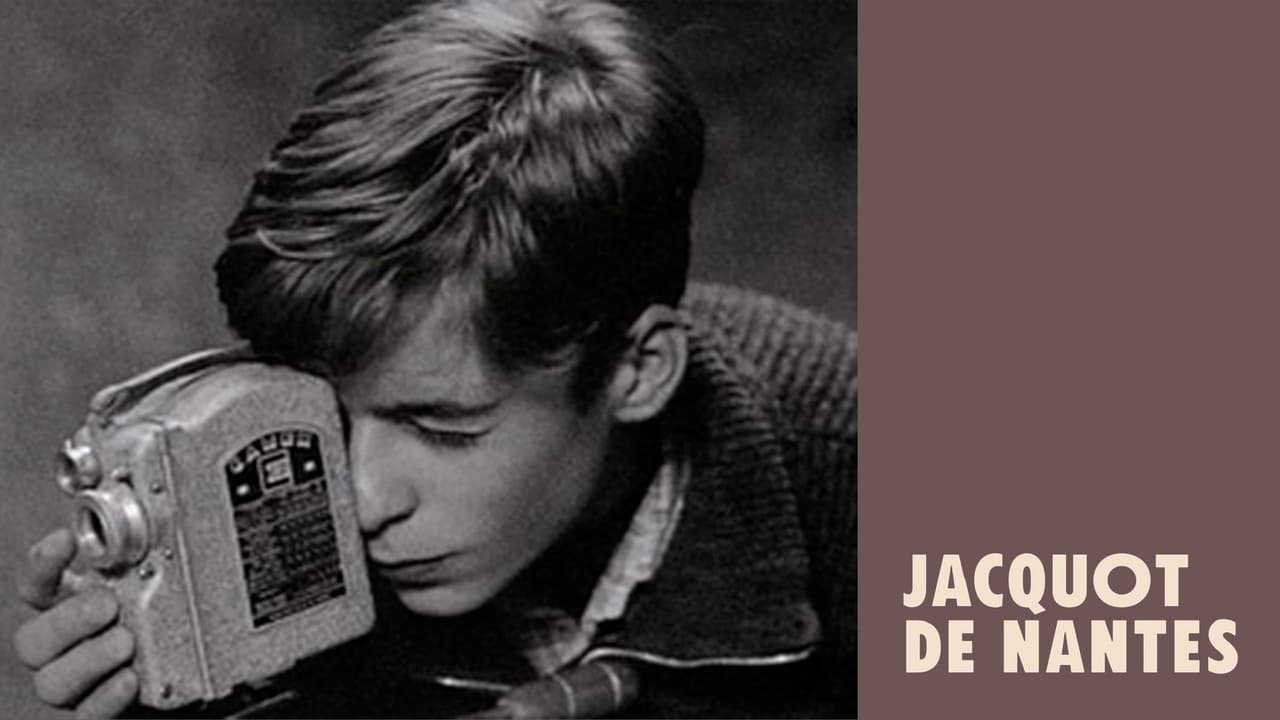

The film primarily exists in two distinct visual realms. The bulk of it consists of beautifully realized, often colour-drained recreations of Demy's formative years in Nazi-occupied and post-war Nantes. We see young Jacquot (played at different ages with remarkable sensitivity by Philippe Maron, Edouard Joubeaud, and Laurent Monnier) discovering the allure of puppet shows, the mechanics of projectors, and the sheer, transformative magic of cinema. Varda doesn't just show us what happened; she evokes the feeling of a child's burgeoning passion, the obsessive drive to create, even with the most rudimentary tools. The scenes of Jacquot painstakingly crafting his first animated films possess a purity and authenticity that feels utterly true to the spirit of anyone who’s ever fallen hopelessly in love with making things.

These recreations aren't slick Hollywood flashbacks. They have a handmade quality, a texture that feels appropriate for depicting memories of a simpler, tougher time. There's a warmth here, an understanding gaze that could only come from someone who knew the subject intimately. It’s like leafing through a cherished family album, guided by the most insightful narrator imaginable.

A Filmmaker's Loving Gaze

Interspersed with these loving recreations are two other elements that elevate Jacquot beyond simple biography. First, Varda weaves in clips from Demy's own beloved films – moments from Lola (1961), The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967). These aren't just celebratory nods; they serve as poignant counterpoints, showing the glorious, colourful fruition of the young boy's dreams we've just witnessed him nurturing. Seeing Catherine Deneuve twirl in Rochefort gains a new layer of meaning when juxtaposed with Jacquot's early, fumbling experiments.

The second, and most emotionally devastating element, is the inclusion of stark, black-and-white close-ups of the real Jacques Demy, filmed shortly before his death in 1990 from complications related to AIDS (though the specific illness is never named). Frail, his skin almost translucent, he observes his own childhood memories being reenacted. He occasionally speaks, reflecting on his life, but mostly, he just is. His presence is a quiet, heartbreaking testament to the fragility of life and the enduring power of the human spirit. Varda's camera doesn't flinch, but its gaze is infinitely compassionate. This isn't exploitation; it's witness. It’s a preservation of the man she loved, even in his final days.

More Than Just Trivia

Knowing the context of the film's creation – that Varda essentially raced against time to complete this tribute while Demy was still alive – imbues every frame with added significance. It wasn't merely a project; it was a final, shared act of creation. Demy himself reportedly consulted on the script and casting, making it a collaboration to the very end. This isn't just a "behind-the-scenes fact"; it's the heart of the film. It transforms Jacquot de Nantes from a charming look at a filmmaker's youth into a profound meditation on love, memory, and the role art plays in confronting mortality. It asks us, implicitly, what truly lasts? What moments shape us? And how can cinema hold onto something – or someone – precious?

The Echo of Childhood Dreams

While perhaps not a typical Friday night rental from Blockbuster back in the day, Jacquot de Nantes offers something uniquely rewarding for anyone who loves film. It speaks directly to the origins of creativity, that inexplicable spark that drives someone to tell stories or capture images. For those of us who grew up haunting video stores, intoxicated by the possibilities held within those plastic boxes, there's a recognizable echo in young Jacquot's wide-eyed wonder. The technology has changed, the CRTs are gone, but the passion? That remains timeless. Varda, with her characteristic wisdom and warmth, reminds us that even the grandest cinematic dreams often start small, in a dusty attic or a darkened garage, with little more than imagination and makeshift tools.

This film is a gentle, poignant exploration of where a life dedicated to cinema begins, made all the more powerful by the knowledge of where, and how, that life was ending. It's a celebration filtered through the lens of impending loss, a love letter written in light and shadow.

Rating: 9/10

Jacquot de Nantes earns this high mark for its profound emotional honesty, Varda's masterful blend of documentary and recreation, and its unique power as both a loving tribute and a meditation on life, art, and mortality. The performances of the young actors are pitch-perfect, capturing the essence of burgeoning creativity, while the presence of Demy himself provides an unforgettable, heartbreaking anchor. It’s a film that stays with you, a quiet masterpiece born from love and loss.

It leaves you contemplating not just Demy's life, but the very nature of memory itself – how we reconstruct our pasts, and how cinema can offer a form of fragile, beautiful immortality.