There’s a profound quietness that settles over Keith Gordon’s A Midnight Clear (1992), a stillness that feels almost alien amidst the usual cacophony of World War II cinema. Forget the bombastic heroism or the relentless grit often depicted; this film, adapted from William Wharton's semi-autobiographical novel, invites us into a snow-laden pocket of the Ardennes forest during Christmas 1944, where the loudest sounds are often the crunch of boots on snow or the strained whispers between young men trying desperately to understand a war that makes no sense. It wasn't the tape I reached for seeking adrenaline back in the day, but the one that lingered, posing questions that echoed long after the VCR clicked off.

An Uneasy Truce in Winter's Grip

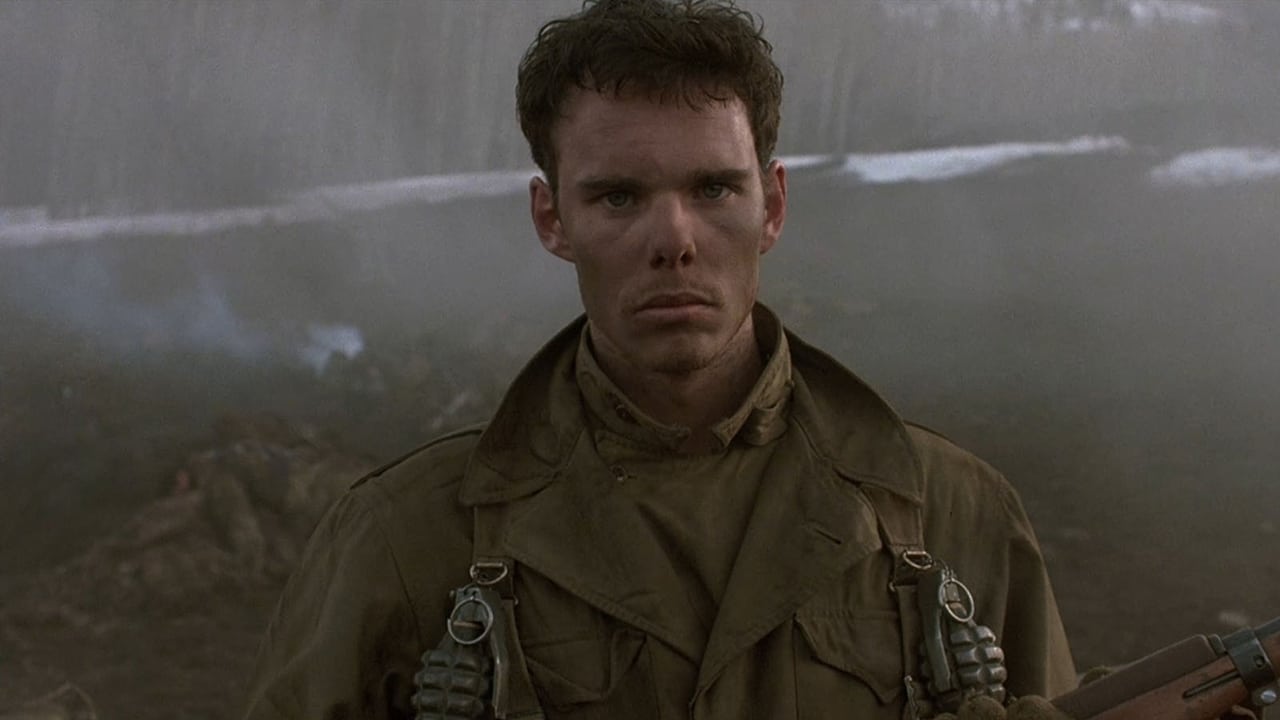

The setup is deceptively simple: a small American Intelligence and Reconnaissance platoon, comprised of soldiers chosen for their high IQs but weary beyond their years, holes up in an abandoned château. Led nominally by the pragmatic Sergeant Wilkins (Peter Berg) but spiritually guided by the sensitive Private Will Knott, nicknamed "Won't" (Ethan Hawke, in a performance hinting at the thoughtful intensity he'd later master), they soon discover they're not alone. A group of German soldiers occupies the woods nearby, but their behavior is… strange. They seem less interested in fighting than in making contact, leaving behind unnerving signs like a snowman dressed in a German uniform or engaging in eerie, echoing calls across the frozen landscape. What unfolds is less a battle and more a fragile, almost surreal negotiation between enemies who find themselves sharing a common exhaustion and a desperate desire just to survive the winter.

Gordon's Quiet Command

As a director, Keith Gordon, whom many of us first knew from his acting roles in films like John Carpenter's Christine (1983) or the comedy Back to School (1986), brings a remarkable sensitivity to the material. This was only his second feature, following the intense The Chocolate War (1988), and his focus is squarely on the psychological toll of conflict, the absurdity of lines drawn on a map forcing young men to kill each other. He deliberately sidesteps conventional action sequences, instead building tension through atmosphere, whispered conversations, and the palpable fear and confusion etched on the actors' faces. The cinematography captures the stark beauty and isolating nature of the snowbound forest, creating a visual poetry that contrasts sharply with the underlying menace. It’s a landscape both fairytale-like and deeply threatening. Doesn't that chilling beauty somehow amplify the tragedy waiting in the wings?

A Brotherhood on the Brink

The film is anchored by its exceptional ensemble cast, a roster of young actors many of whom were just finding their footing but would soon become very familiar faces. Alongside Hawke and Berg, we have Kevin Dillon as the volatile Mel Avakian, Arye Gross as the scholarly Stan Shutzer, a very grounded Gary Sinise (years before his iconic Lt. Dan in Forrest Gump) as Vance "Mother" Wilkins, and Frank Whaley as the deeply troubled Paul "Father" Mundy. Their interactions feel utterly authentic; the banter, the shared anxieties, the flashes of youthful hope breaking through the weariness. They genuinely seem like boys thrust into men's roles, their intelligence offering little shield against the war's inherent madness. Gordon made a point of casting actors close to the actual ages of the characters in Wharton’s book, a decision that pays dividends in the film's raw vulnerability. You feel their shared history, their dependence on one another in this isolated pocket of hell.

Echoes from the Ardennes: Behind the Scenes

Finding A Midnight Clear on the video store shelf often felt like discovering a hidden gem. Its initial theatrical run was muted – despite critical acclaim, it grossed only about $1.5 million against its modest $5 million budget. Its true audience found it later, through VHS rentals and cable screenings, drawn perhaps to its thoughtful difference. Filmed primarily in the snowy landscapes around Park City, Utah, the production itself mirrored the isolation depicted on screen. The relatively low budget likely contributed to the film’s intimate feel, forcing a focus on character and atmosphere over grand-scale spectacle. Wharton's novel itself drew heavily on his own WWII experiences, lending the story a haunting layer of truth. Gordon fought hard to preserve the novel’s somber tone and anti-war message, resisting studio pressure for a more conventional or uplifting ending. It's a testament to his conviction that the film remains as quietly devastating as it does.

The Fragility of Peace

At its heart, A Midnight Clear explores the painful absurdity of war and the flickering possibility of shared humanity even across enemy lines. The tentative moments of connection – a shared snowball fight, the haunting exchange of Christmas carols across the snowy expanse – are imbued with a fragile hope that makes the inevitable descent back into conflict all the more heartbreaking. It asks us to consider what happens when the rules of engagement break down, replaced by something far more complicated and human. What does it mean when soldiers on opposing sides recognize their shared desire simply to live? The film offers no easy answers, leaving the viewer to grapple with the senselessness of it all.

***

Rating: 9/10

A Midnight Clear earns this high score for its masterful direction, exceptional ensemble cast delivering deeply authentic performances, haunting atmosphere, and its courage to be a quiet, contemplative anti-war film that prioritizes psychological depth over spectacle. It’s a film that doesn't shout its message but whispers it, leaving a lasting impression of profound sadness and humanity.

It remains a standout from the early 90s indie scene, a film that perhaps felt slightly out of time upon release but whose themes of miscommunication and the human cost of conflict feel startlingly relevant today. It’s one of those VHS discoveries that truly stays with you, a reminder that sometimes the most powerful stories are found not in the heat of battle, but in the deafening silence that follows.