Okay, settle in. Let's talk about a tape that likely sat ominously on the rental shelf, its stark helmet cover hinting at something far more unsettling than your typical 80s war flick. Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987) wasn’t just another Vietnam movie; it was, and remains, a chilling dissection of the machinery that turns boys into killers, presented with Kubrick's signature clinical precision. Pulling this one from its cardboard sleeve always felt significant, like you were committing to something intense.

A Tale of Two Wars

What immediately strikes you, even decades later, is the film's jarring, almost binary structure. Based on the novel The Short-Timers by Gustav Hasford (who co-wrote the screenplay with Kubrick and journalist Michael Herr, author of the seminal Vietnam account Dispatches), the film cleaves itself neatly in two. First, the infamous Parris Island boot camp sequence, a masterclass in psychological degradation. Then, the shift to the shattered urban landscapes of Hue City during the Tet Offensive. Some viewers back in the day found this abrupt shift disorienting, almost like two separate films stitched together. But isn't that the point? The film argues, through its very form, that the psychological warfare waged in basic training is inextricably linked to the physical warfare that follows. One creates the necessary conditions for the other.

The Furnace of Parris Island

The first half is dominated by the unforgettable Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, played with terrifying authenticity by R. Lee Ermey. Here’s a piece of trivia that feels almost preordained: Ermey, a real-life former Marine drill instructor, wasn't originally cast in the role. He was initially hired as a technical advisor, but his relentless, profane, and highly creative improvisational insults, captured on an audition tape he made himself, convinced Kubrick he was Hartman. Apparently, Kubrick estimated that 50% of Ermey's dialogue was improvised. The result is magnetic and horrifying. Hartman isn't just shouting; he's systematically dismantling identities, rebuilding recruits in the Corps' image. We see this primarily through the eyes of Private Joker (Matthew Modine, providing a crucial, observant anchor) and the tragic Private Pyle (Vincent D'Onofrio).

D'Onofrio's transformation is staggering. Gaining a reported 70 pounds for the role (breaking Robert De Niro's record from Raging Bull at the time), he embodies the slow, agonizing breakdown of Leonard Lawrence into the vacant-eyed Pyle. His journey from inept recruit to dissociated killer is one of the most harrowing character arcs committed to film. The infamous latrine scene (Spoiler Alert! if you somehow haven't seen it) remains profoundly disturbing, the culmination of relentless dehumanization. Watching it unfold, you feel complicit, trapped within the suffocating confines of the barracks. Kubrick uses sterile compositions and symmetrical framing to emphasize the rigid, unforgiving nature of this environment. It feels less like training, more like psychological torture under fluorescent lights.

Welcome to The Suck

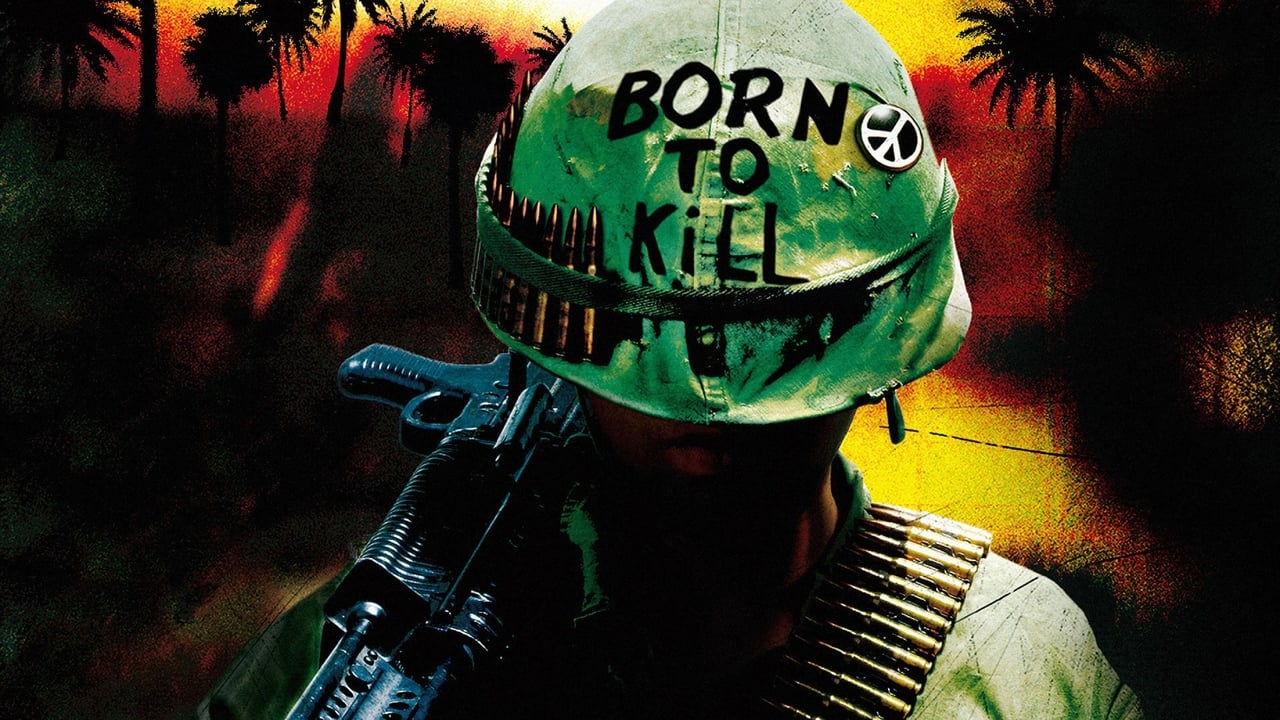

Then, abruptly, we're in Vietnam. The pristine hell of Parris Island gives way to the chaotic, rubble-strewn hell of war. Joker, now a combat correspondent for Stars and Stripes, navigates this new landscape, his helmet ironically adorned with both a peace symbol and the words "Born to Kill." This duality – the coexistence of conflicting ideals within a single soldier – is central to the film's exploration of war's inherent contradictions. Matthew Modine carries this section well, his character acting as our somewhat detached guide through the insanity. He retains a core of his former self, but the experiences are undeniably reshaping him.

Kubrick, ever the meticulous craftsman, famously recreated the ruins of Hue City not in Southeast Asia, but at the abandoned Beckton Gas Works in East London. This required importing Spanish trees and 200 palm trees from Hong Kong, along with strategically demolishing parts of the defunct industrial site under the guidance of production designer Anton Furst (who would later win an Oscar for his work on Tim Burton's Batman (1989)). The effect is surreal – a meticulously constructed apocalypse that feels both artificial and terrifyingly real. The combat sequences, particularly the climactic sniper hunt, are tense and brutal, devoid of heroic fanfare. Kubrick focuses on the confusion, the fear, and the sudden, arbitrary nature of death. The soldiers, including the imposing Animal Mother (Adam Baldwin), feel less like action heroes and more like pawns navigating a landscape of sheer survival.

Kubrick's Cold Eye

Unlike Oliver Stone's contemporaneous Platoon (1986), which wore its heart and its anti-war message more overtly on its sleeve, Full Metal Jacket maintains a colder, more observational distance. Kubrick isn't interested in easy sentiment or moralizing. He presents the dehumanizing process and its consequences with chilling clarity, leaving the viewer to grapple with the implications. The film’s use of jaunty pop songs like "Surfin' Bird" or Nancy Sinatra's "These Boots Are Made for Walkin'" against scenes of military precision or impending dread creates a profound sense of unease, highlighting the dissonance between the sanitized image of war and its grim reality.

Does this detachment make the film less emotionally impactful? For some, perhaps. But for me, the power lies precisely in this clinical observation. It forces a confrontation with uncomfortable truths about training, conformity, and the psychological toll of conflict. What does it truly mean to be "born to kill"? Can humanity endure within a system designed to extinguish it? The film doesn't offer easy answers, which is part of why it continues to resonate.

The Verdict on the VHS

Full Metal Jacket was a challenging watch back on a fuzzy CRT, the grain somehow adding to the grime and grit. It wasn't the gung-ho action promised by some box art, but something far more complex and disturbing. It provoked discussion, maybe even arguments, after the credits rolled and the VCR whirred to a stop. It stands as a testament to Kubrick's singular vision – a film that dissects the culture of war as much as war itself. The performances, particularly Ermey's force-of-nature turn and D'Onofrio's devastating portrayal, are burned into cinematic memory. The Parris Island sequence alone solidifies its place as essential viewing.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score reflects the film's undeniable power, masterful direction, iconic performances, and unflinching gaze into the abyss of military conditioning and combat. Its bifurcated structure, while potentially jarring, serves a crucial thematic purpose, making it a unique and intellectually stimulating entry in the war film canon. It might lose a single point for the slightly less focused feel of the second half compared to the laser precision of the first, but its overall impact is immense.

Full Metal Jacket isn't just a war movie; it's a Kubrickian puzzle box about identity, violence, and the dark paradoxes of human nature, leaving you with the haunting refrain of the Mickey Mouse March sung by soldiers marching into the smoke. What lingers most is the chilling efficiency of the machine.