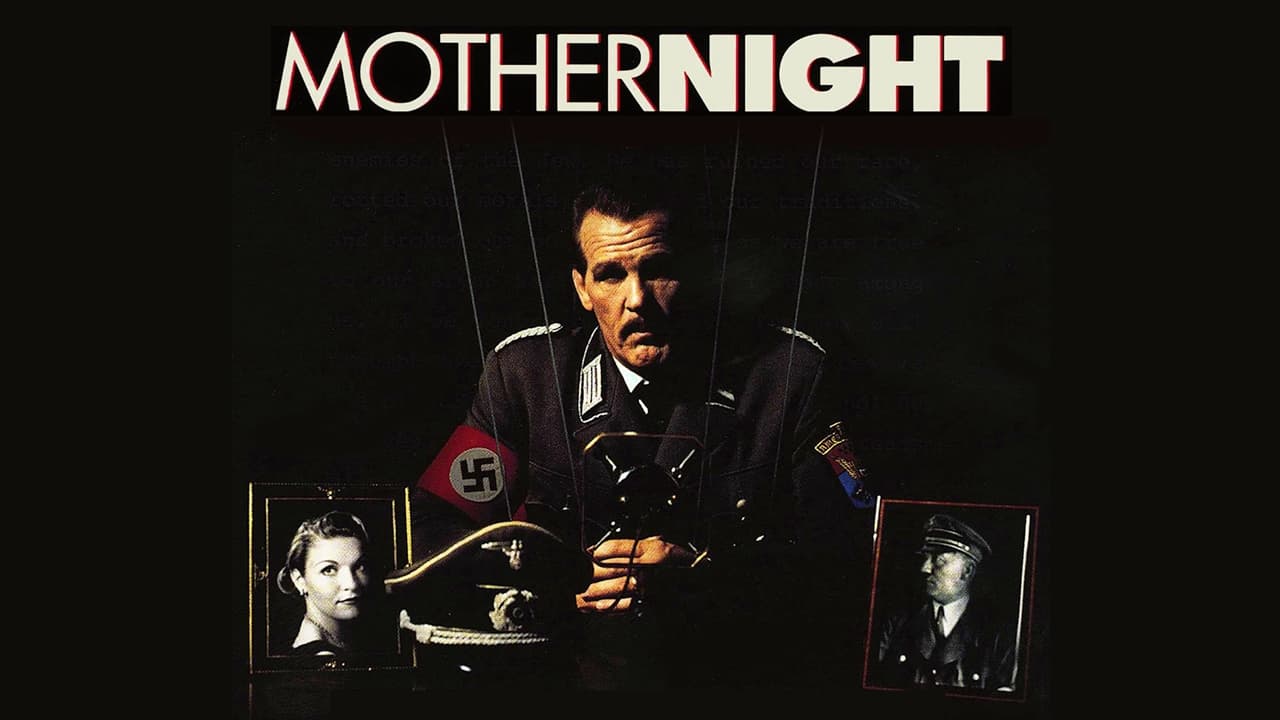

"My name is Howard W. Campbell, Junior. I am an American by birth, a Nazi by reputation, and a nationless man by inclination." It’s with these chillingly direct words, delivered from the confines of an Israeli prison cell awaiting trial for war crimes, that Mother Night (1996) immediately plunges us into a moral labyrinth. There are films that entertain, films that thrill, and then there are films like this – ones that quietly burrow under your skin and force a reckoning with uncomfortable truths about identity, complicity, and the stories we tell ourselves. Finding this on a dusty video store shelf back in the day felt like unearthing something significant, something demanding more than just a casual watch.

### The Playwright Who Played the Spy

Based on the darkly satirical 1961 novel by the inimitable Kurt Vonnegut, Mother Night presents the complex life of Howard W. Campbell Jr. A moderately successful American playwright living in Germany before World War II, he finds himself recruited by U.S. intelligence. His mission: rise through the ranks of the Nazi propaganda machine, becoming a virulent voice on the radio waves, all while secretly transmitting coded messages back to the Allies through his coughs, pauses, and inflections. He plays his part too well, becoming a celebrated figure in the Reich and a reviled traitor in the eyes of the world. After the war, he lives in anonymous obscurity in New York, haunted by his past and the ghosts of his actions, until his identity is inevitably exposed, forcing him to confront the impossible question: Was he a hero or a monster? Or, perhaps more disturbingly, was he simply what he pretended to be?

### Nolte's Towering, Troubled Soul

At the heart of the film's power is a truly remarkable performance by Nick Nolte. Forget the grizzled action roles or the later eccentricities; here, Nolte embodies Campbell with a profound weariness, a palpable sense of a soul fractured by its own necessary deceptions. His Campbell isn't a caricature of evil or a clear-cut hero. He's a man adrift, intelligent yet passive, swept along by historical tides and his own ambiguous choices. Nolte conveys the intellectual vanity that allowed Campbell to believe he could play such a dangerous game unscathed, alongside the crushing weight of the consequences. There's a vulnerability beneath the carefully constructed facade, a quiet desperation that makes his predicament so compelling and tragic. It’s a performance less about overt emoting and more about inhabiting a space of deep moral exhaustion, and it ranks among Nolte's finest work.

### Echoes in the Ensemble

Surrounding Nolte is a superb supporting cast who amplify the film's themes. Sheryl Lee (forever etched in our minds as Laura Palmer from Twin Peaks) is heartbreakingly effective as Helga Noth, Campbell's beloved wife, presumed dead but perhaps returned – or is it her younger sister Resi, a dangerous zealot? Lee navigates this dual role with ethereal grace and unsettling intensity, embodying the elusive nature of truth and love in Campbell's shattered world. Alan Arkin, effortlessly watchable as always, plays George Kraft, Campbell's seemingly benign neighbour and chess partner, who may harbour secrets of his own. And look out for John Goodman in a small but memorable role as a boisterous, misguided American spy handler, adding a layer of bureaucratic absurdity that feels distinctly Vonnegutian. Director Keith Gordon (A Midnight Clear (1992), The Chocolate War (1988)), himself an actor turned thoughtful filmmaker, orchestrates these elements with sensitivity. He doesn't rush the narrative, allowing the atmosphere of paranoia and introspection to build, focusing on character and the claustrophobia of Campbell’s internal prison long before he reaches the physical one.

### Adapting Vonnegut and Finding the Film

Bringing Vonnegut's blend of satire, tragedy, and humanism to the screen is notoriously tricky. Screenwriter Robert B. Weide (who would later direct the excellent documentary Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time) spent years championing this project, and his passion shows. The script wisely retains Vonnegut's framing device and much of his bleak wit, translating the novel's core message with fidelity and intelligence. It's a testament to Weide's dedication that the film got made at all. Even Vonnegut himself seems to have approved, making a brief, amusing cameo early in the film – a knowing wink to the audience. Released amidst the slicker fare of the mid-90s, Mother Night was perhaps too thoughtful, too challenging for mainstream success. It reportedly cost around $5.5 million but barely made a dent at the box office, grossing under $1 million. It became, like so many unique films of the era, a discovery – something you’d recommend in hushed tones to a fellow cinephile after finding the tape tucked away in the drama section.

### The Weight of Pretence

"We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be." This line, central to both the novel and the film, resonates long after the credits roll. Mother Night doesn't offer easy answers about Campbell's guilt or innocence. It suggests that intentions, however noble, might be irrelevant when the performance of evil contributes to actual evil. Can you truly separate the actor from the role when the stage is the world and the consequences are measured in lives? The film forces us to consider the slippery slope of compromise, the seductive nature of belonging (even to a monstrous cause), and the enduring question of how history ultimately judges our actions, regardless of the secrets we keep. It’s a profoundly unsettling thought, handled here with gravity and nuance.

Rating: 8.5/10

Justification: Mother Night earns this high rating for its courageous exploration of complex moral themes, anchored by an exceptional lead performance from Nick Nolte. Keith Gordon's direction is assured and sensitive, the adaptation is remarkably faithful to Vonnegut's spirit, and the supporting cast is uniformly strong. While its deliberate pacing and somber tone might not appeal to everyone, its intellectual depth and emotional resonance make it a standout drama from the 90s. The slight deduction reflects that its very thoughtfulness perhaps limited its reach, making it more of a cherished cult item than a widely embraced classic.

It’s a film that doesn’t fade easily, leaving you turning over Campbell’s predicament in your mind. What defines us more: our secret intentions or our public actions? Mother Night offers no simple verdict, only the haunting echo of a life lived in the devastating ambiguity between the two.