It begins almost like a dark fairytale, doesn't it? A woman sits patiently by a tin bath in a field, waiting for her drunken husband to finish his lament before calmly drowning him. This stark, strangely matter-of-fact opening sets the stage for Drowning by Numbers (1988), a film that arrived on VHS shelves like a cryptic puzzle box amidst the usual action heroes and romantic comedies. Finding this one in the 'Art House' section of the local video store felt like uncovering a secret – a film that promised something intricate, perhaps unsettling, and utterly unlike anything else playing on the neighbours' CRTs.

A Grim Game of Consequences

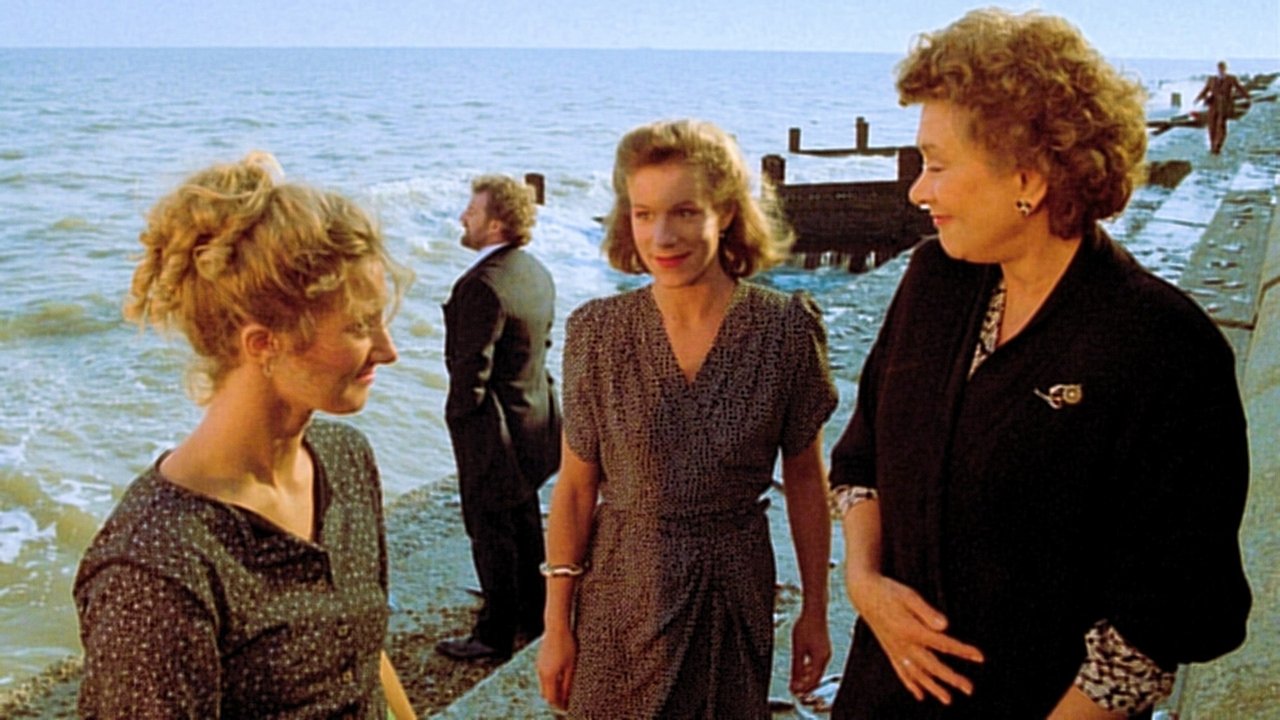

At its heart, the plot is deceptively simple, yet laced with a peculiar logic. We follow three women, all named Cissie Colpitts – grandmother (Joan Plowright), mother (Juliet Stevenson), and daughter (Joely Richardson) – each dissatisfied with their husbands for varying, sometimes mundane, reasons. The solution? Drowning. One after another, they dispatch their spouses, enlisting the local coroner, Madgett (Bernard Hill), to cover their tracks. Madgett, lonely and increasingly desperate for affection, complies in exchange for sexual favours, becoming entangled in the Cissies' morbid game, a game governed by rules as arbitrary and complex as life itself.

Greenaway's Counting Canvas

This isn't just a narrative; it's an elaborate construction by director Peter Greenaway, known then as now for his intensely visual and structurally rigorous filmmaking (think The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover the following year). Drowning by Numbers is perhaps his most famous formal experiment. The numbers 1 to 100 appear sequentially throughout the film, sometimes blatantly displayed on a jersey or signpost, other times cunningly hidden within the meticulously composed shots. Watching it back then, especially on a fuzzy VHS paused frame-by-frame on a CRT, spotting the numbers became part of the viewing experience itself – a meta-game layered onto the deadly games played by the characters. Was it essential to understanding the plot? Not really. But it underscored Greenaway's fascination with imposing order, however arbitrary, onto the messy realities of sex, death, and the English countryside.

The visual style is pure Greenaway: painterly compositions reminiscent of Dutch Masters, static shots held just long enough to feel deliberate, and a landscape (the Suffolk coast and Kentish countryside) that feels both idyllic and strangely menacing. Coupled with Michael Nyman's iconic, driving score – famously derived from a theme in Mozart's Sinfonia Concertante K.364 – the film achieves a hypnotic, almost ritualistic quality. Nyman's music, looping and building, becomes as integral to the film's structure as the counting itself, mirroring the repetitive cycles of the games and the murders. It’s a score that burrows into your memory, instantly recognisable even decades later.

The Three Cissies and Their Fool

The performances are key to making this strange brew work. Joan Plowright, the matriarch, exudes a chilling pragmatism masked by grandmotherly charm. Juliet Stevenson brings a weary sensuality and sharp intelligence to her Cissie, while Joely Richardson portrays the youngest Cissie with a more detached, almost playful curiosity about the grim proceedings. Together, they form a fascinating trio – less overtly emotional, more bound by a shared, amoral purpose and a darkly comic understanding of the men in their lives. Their chemistry feels less like familial warmth and more like conspiratorial alignment.

And then there's Bernard Hill as Madgett. Fresh off his memorable role in Boys from the Blackstuff (1982), Hill gives a wonderfully tragicomic performance. Madgett is a man utterly consumed by his obsessions – morbid pathology and a desperate need for connection – making him pitiably easy for the Cissies to manipulate. He’s the fool in their game, his increasing desperation providing much of the film’s bleak humour and pathos. Does his plight make us question the women's actions, or simply highlight the absurdity of his own choices?

More Than Just Numbers

Beyond the stylistic flourishes and dark humour, Drowning by Numbers touches on themes of control, mortality, and the bizarre rules we invent to navigate life. The games played throughout the film – Hangman, Tug of War, Deadman's Catch – aren't just quirky details; they reflect the larger game of manipulation and survival the Cissies are engaged in. Death is treated with an almost procedural detachment, stripped of sentimentality, much like the cataloguing of insects or the coroner's clinical observations. It forces you to consider: are human lives just pawns in elaborate, often pointless, games?

Rewatching it now, the film feels like a perfectly preserved artifact from a time when art-house cinema could be daringly experimental and unapologetically intellectual, yet still find a place on those video rental shelves. It wasn't aiming for mass appeal; it was aiming for a specific, challenging experience. I remember renting this tape, its distinctively designed Palace Pictures box promising something sophisticated and perhaps a little strange. It certainly delivered. It’s a film that doesn’t offer easy answers or emotional catharsis, but rather invites you into its meticulously crafted, morbidly funny, and oddly beautiful world.

Rating: 8/10

This rating reflects the film's sheer artistic audacity, its unforgettable visual and auditory style, and the compellingly detached performances. It's a challenging watch, intentionally cold and formal at times, which prevents it from reaching universal appeal (hence not a 9 or 10). However, its unique structure, dark wit, and the indelible mark of Greenaway's vision make it a standout piece of 80s British cinema. It’s a film that sticks with you, less for its plot twists and more for its strange, resonant atmosphere and the unsettling questions it leaves hanging in the air. What lingers most is that curious blend of mathematical precision and utter human chaos.