The air hangs thick and humid, shimmering like the iridescent scales of the creatures at its heart. Forget jump scares; Tsui Hark’s Green Snake (1993) coils around you with a different kind of unease – a heady mix of sensual awakening, ancient magic, and the tragic weight of impossible desires. Watching it back then, perhaps on a slightly fuzzy VHS rented from a store shelf crowded with more conventional fantasies, felt like stumbling upon a forbidden text, vibrant and intoxicating, its colours bleeding through the screen in a way few Western films dared. It wasn't just fantasy; it felt like a fever dream painted onto celluloid.

A World Awash in Color and Desire

From its opening moments, Green Snake plunges the viewer into a world saturated with impossible hues. Tsui Hark, already a master craftsman known for visually dynamic films like Zu Warriors from the Magic Mountain (1983) and the Once Upon a Time in China series, pushes his aesthetic to its absolute limit here. Based on the novel by Lilian Lee (who also co-wrote the screenplay), which itself reinterprets the classic Chinese Legend of the White Snake, the film is a visual feast. The sets are fantastical, often deliberately theatrical, draped in flowing silks that ripple like water or flame. Cinematographer Ko Chiu-Lam fills the frame with deep blues, venomous greens, passionate reds, and ethereal whites, creating a heightened reality where mortal and supernatural realms bleed into one another. The score, a haunting blend of traditional instrumentation and synth undertones by James Wong and Mark Lui, perfectly complements this intoxicating atmosphere, underscoring both the seductive allure and the looming tragedy.

Sister Serpents

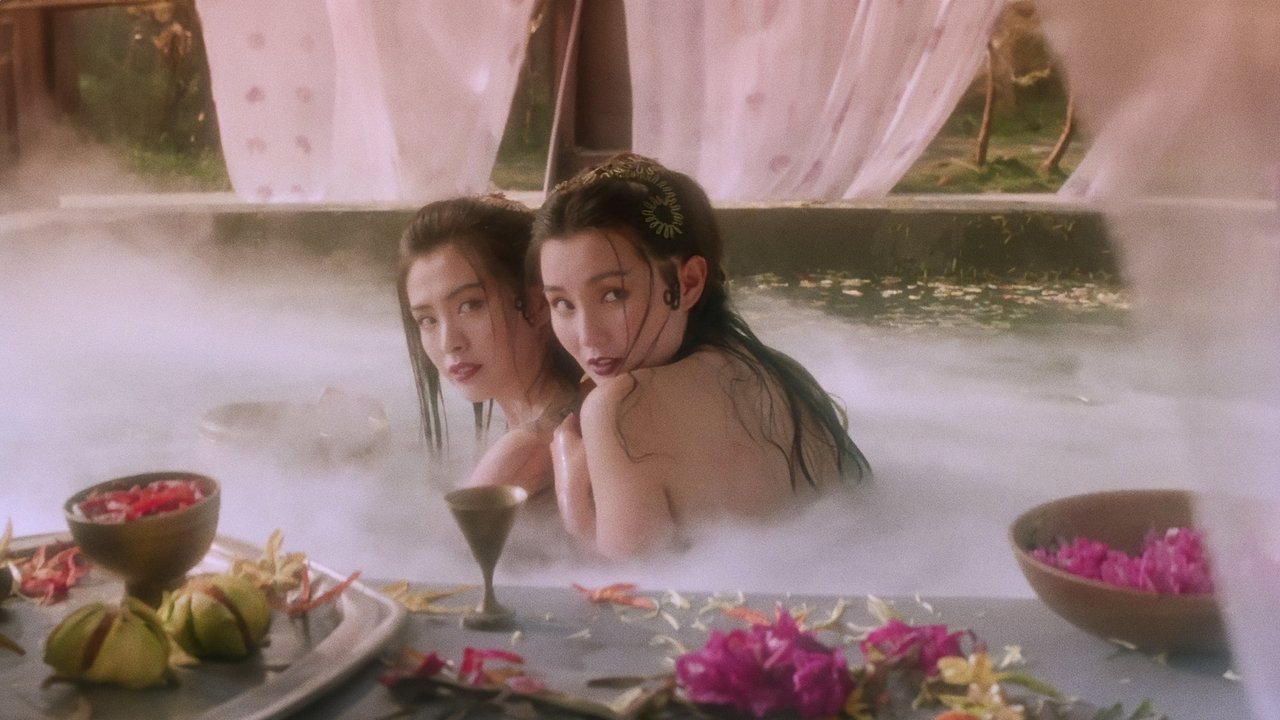

At the core of this visual splendor are the titular Green Snake, Siu Ching, played with mischievous, captivating energy by Maggie Cheung, and her elder sister, the White Snake, Bak Seiuzhen, embodied with grace and yearning by Joey Wong (forever iconic from A Chinese Ghost Story (1987)). They are ancient snake spirits who, after centuries of cultivation, gain the ability to take human form. While White Snake seeks true love and the full experience of humanity with the naive scholar Hsui Xien (Wu Hsing-kuo), Green Snake is more impulsive, driven by curiosity, jealousy, and a raw, untamed sensuality. Their bond is the film's emotional anchor – a complex tapestry of loyalty, rivalry, and shared otherness. Cheung, in particular, is mesmerizing, conveying Siu Ching’s serpentine nature through fluid movements and expressive eyes that flicker between innocence and ancient cunning. It's a performance that required immense physical control, blending dance-like choreography with demanding wirework, a hallmark of Hong Kong action cinema pushed into the realm of sensual fantasy.

Retro Fun Facts: Conjuring the Myth

Adapting Lilian Lee's revisionist take on the legend wasn't straightforward. Tsui Hark consciously chose to shift the focus from the traditional heroine, White Snake, to the more ambiguous and volatile Green Snake, exploring themes of envy and the confusing, often painful, nature of human emotions from an outsider's perspective. This shift gives the film its unique edge. The visual effects, a blend of practical techniques, intricate wire-fu, and early digital flourishes, might seem somewhat dated now, especially the CGI snake tails, but in 1993, they contributed to the film's otherworldly, dreamlike quality. There’s a palpable physicality to the way the sisters move, a slithering grace that wirework enhances rather than hides. Rumour has it that the intense water sequences, particularly the climactic flood, were incredibly challenging to film, pushing the boundaries of practical effects capabilities at the Golden Harvest studios before the digital age truly took over Hong Kong filmmaking. Despite its visual ambition and star power, Green Snake wasn't a massive box office hit in Hong Kong upon release (earning around HK$9.5 million), but its reputation has only grown, cementing its status as a cult classic adored for its unique artistry.

The Monk and the Moral Maze

Opposing the snakes' desires is the rigidly devout Buddhist monk Fahai, played with imposing stoicism by Vincent Zhao (who also starred in Tsui Hark's Once Upon a Time in China IV). He represents unwavering spiritual law, viewing the snakes' love and aspirations as unnatural transgressions. Yet, even Fahai is not immune to temptation, leading to fascinating confrontations charged with repressed desire and philosophical conflict. Is emotion inherently corrupting? Can love exist outside prescribed boundaries? The film doesn't offer easy answers, painting Fahai not as a simple villain, but as a man wrestling with his own dogma in the face of forces he cannot fully comprehend. Doesn't his internal conflict make the snakes' plight even more poignant?

Legacy of a Lush Phantasm

Green Snake remains a singular achievement in Tsui Hark's filmography and a standout gem of 90s Hong Kong cinema. It's a film that dares to be excessive, blending high art visuals with folk legend, melodrama, and moments of startling beauty and tragedy. Its influence can be seen in later fantasy films that embraced more vibrant, stylized aesthetics. It’s a film that rewards rewatching, revealing new layers in its dense visuals and complex emotional currents each time. The feeling it leaves isn't one of fright, but of a profound, melancholic beauty – the ache of wanting something just beyond your grasp.

---

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's stunning visual artistry, its bold thematic exploration, the captivating central performances by Maggie Cheung and Joey Wong, and its enduring power as a unique piece of fantasy cinema. While some effects show their age, they rarely detract from Tsui Hark's overwhelming and cohesive artistic vision. The sheer ambition and emotional resonance earn it a high mark.

Green Snake is more than just a fantasy film; it's an opulent, sensual poem on screen, a reminder of a time when Hong Kong cinema was bursting with untamed creativity and wasn't afraid to be utterly, breathtakingly strange. It remains a vibrant, intoxicating experience, a tape you'd rewind not just for the spectacle, but for the haunting feeling it left behind.