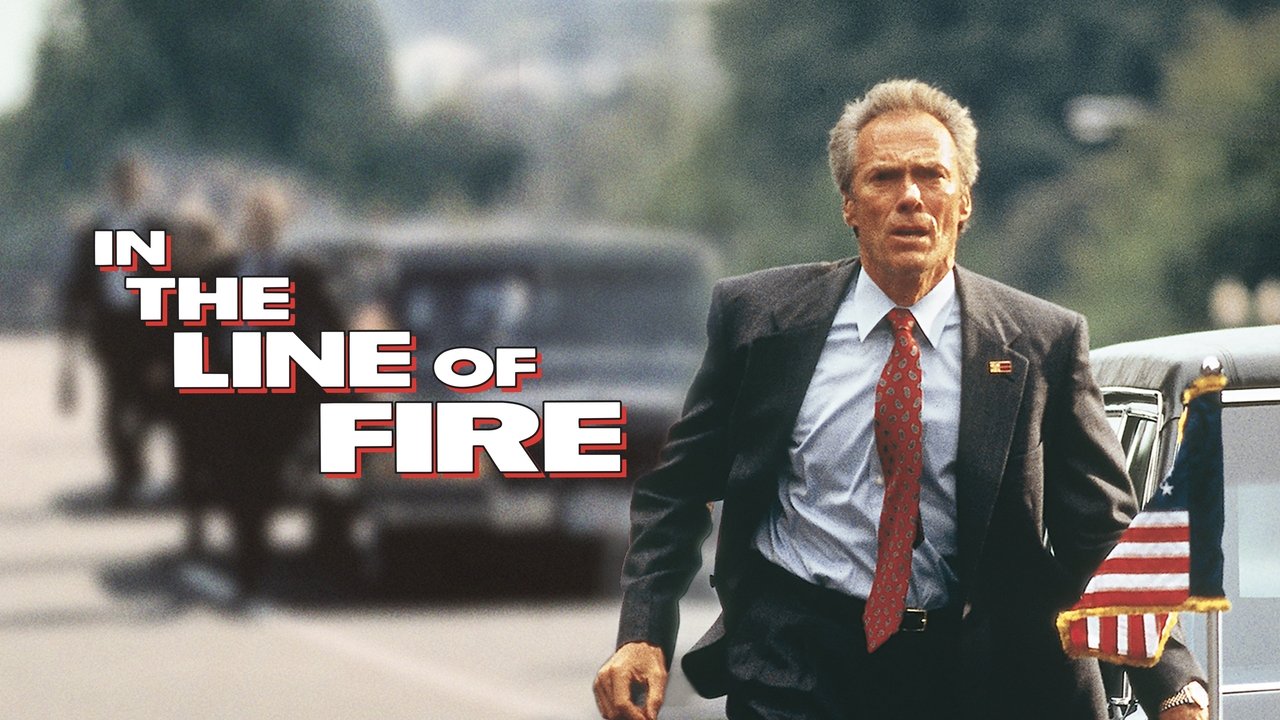

Some ghosts refuse to stay buried, especially when they whisper threats down a crackling phone line, echoing failures decades old. That's the chilling frequency Wolfgang Petersen tuned into with In the Line of Fire (1993), a thriller that felt less like an action romp and more like a slow-burn fuse inching towards an inevitable explosion, right there on your grainy CRT screen. It wasn't just about saving the President; it was about confronting a past that haunted Secret Service Agent Frank Horrigan, played with weary gravitas by Clint Eastwood, like a phantom limb aching from that fateful day in Dallas.

Echoes in the Static

The genius of Jeff Maguire’s script – a screenplay that reportedly languished for over a decade before finding a home at Castle Rock Entertainment – lies in its psychological depth. This isn't just a procedural. It's a character study wrapped in a high-stakes game of cat and mouse. Horrigan is the last active agent who was on JFK's detail in 1963, and that failure permeates every aspect of his existence. He’s haunted, running on cynical fumes and cheap whiskey, a relic in an agency moving towards younger, fitter agents like Lilly Raines (Rene Russo, bringing sharp intelligence and believable chemistry). When a meticulously clever assassin calling himself "Booth" (later identified as Mitch Leary) contacts Horrigan, boasting of his plan to kill the current President, it becomes intensely personal. It's Frank's one shot at redemption, a chance to finally exorcise the ghosts of Dealey Plaza.

The Master of Manipulation

And what a ghost Leary is. John Malkovich, in an Oscar-nominated performance that still sends shivers down the spine, crafts one of the truly unforgettable screen villains of the 90s. Leary isn't a cackling madman; he's terrifyingly intelligent, calculating, and possessed of a chillingly calm demeanor that masks a profound sense of betrayal and rage. His phone calls with Horrigan are masterpieces of psychological warfare. It’s a known piece of film lore that Malkovich heavily improvised many of these taunting exchanges, injecting a volatile unpredictability that feels disturbingly real. He dissects Frank’s failures, probes his weaknesses, and seems almost disappointed when Frank doesn’t quite live up to his twisted expectations of a worthy adversary. Remember the quiet menace in his voice, the way he could turn a simple phrase into a veiled threat? Doesn't that performance still feel unnervingly potent?

Crafting Tension, Frame by Frame

Wolfgang Petersen, already known for tense masterpieces like Das Boot (1981), masterfully builds suspense. He uses the procedural elements – the painstaking investigation, the stakeouts, the bureaucratic hurdles – not as filler, but as layers contributing to the pressure cooker atmosphere. The pacing is deliberate, allowing the dread to seep in. Think about those sequences tracking Leary as he meticulously prepares his untraceable composite pistol – a plot point tapping into very real anxieties about undetectable firearms surfacing in the early 90s. The film benefits immensely from its authenticity, utilizing real Secret Service consultants and filming extensively on location in Washington D.C., grounding the extraordinary threat in a believable reality. Seeing agents actually jogging alongside the presidential limo lent a weight that CGI-heavy sequences often lack.

Retro Fun Facts: The Road to the Screen

Getting In the Line of Fire made was its own kind of long game. Maguire’s script, originally titled "Someone Else's Secret," bounced around Hollywood for years. When Castle Rock finally greenlit it, Clint Eastwood was initially hesitant, feeling perhaps too old for the part. It took Petersen's persuasion to bring him aboard. The film's technical wizardry was also notable for its time; seamlessly inserting a younger Eastwood into archival footage of JFK's 1960s campaign rallies was a groundbreaking digital effect in 1993, blurring the lines between history and fiction in a way that felt both innovative and slightly eerie. Against a budget of around $40 million, the film became a critical and commercial smash, pulling in over $187 million worldwide and securing three Academy Award nominations (Malkovich for Supporting Actor, Maguire for Original Screenplay, and Anne V. Coates for Film Editing).

A Legacy Forged in Suspense

Beyond the stellar performances and taut direction, the film’s atmosphere is cemented by Ennio Morricone’s haunting score. It's a melancholy, suspenseful soundscape that perfectly complements Horrigan’s inner turmoil and the ever-present threat. In the Line of Fire stands as more than just a top-tier 90s thriller; it’s a poignant exploration of aging, regret, and the relentless burden of duty. It showed Eastwood could bring vulnerability to his tough-guy persona, gave Malkovich an iconic role, and delivered a brand of intelligent, character-driven suspense that feels increasingly rare. I distinctly remember renting this one, the sturdy clamshell case promising a serious, adult thriller, and it delivered precisely that – a gripping experience that stayed with you long after the tape clicked off.

---

Rating: 9/10

In the Line of Fire earns its high marks through sheer craftsmanship. The razor-sharp script, Petersen's masterful control of tension, Morricone's evocative score, and the unforgettable performances from Eastwood and especially Malkovich create a near-perfect psychological thriller. It felt mature and gripping back on VHS, blending real-world anxieties with deeply personal stakes, and it holds up remarkably well today, a testament to its intelligent construction and timeless themes.

Final Thought: It’s a film that reminds you how terrifying the most dangerous threats can be when they aren’t just monsters or explosions, but chillingly human voices whispering threats of history repeating itself down a lonely phone line.