There are some films that cling to you long after the tape ejects, leaving not a warm glow but a distinct chill, a profound unease that settles deep in your bones. Krzysztof Kieślowski's A Short Film About Killing (1988), originally titled Krótki film o zabijaniu, is undeniably one of those films. Finding this on a dusty video store shelf, perhaps nestled between more colourful action or horror offerings, might have felt like discovering a hidden, somber truth amidst the usual escapism. It doesn't entertain; it confronts. It doesn’t offer easy answers; it forces difficult questions about the very nature of taking a life.

An Unflinching Gaze

Born from the monumental Dekalog television series – specifically expanding on the fifth commandment, "Thou shalt not kill" – this feature-length version garnered international acclaim, including the Jury Prize at Cannes. It arrived as Polish cinema was gaining significant traction in the West, and Kieślowski, alongside his co-writer Krzysztof Piesiewicz, delivered something utterly uncompromising. The premise is stark: we witness two killings. The first is the brutal, seemingly random murder of a taxi driver, Waldemar Rekowski (Jan Tesarz), by a disaffected youth, Jacek Łazar (Mirosław Baka). The second is the calculated, state-sanctioned execution of Jacek for his crime, observed through the eyes of his idealistic young lawyer, Piotr Balicki (Krzysztof Globisz).

Kieślowski presents these acts not with sensationalism, but with a horrifying, almost unbearable realism. The violence isn't stylized or quick; it's protracted, clumsy, agonizing. Jacek’s strangling of the taxi driver is drawn out, filled with desperate struggle and pathetic indignity. Similarly, the sequence depicting Jacek’s execution is meticulously detailed, showcasing the bureaucratic coldness, the technical hitches, the sheer physicality and terror of extinguishing a human life. The film forces us to watch, denying us the comfort of looking away, ensuring the weight of both acts lands with equal, devastating force.

Warsaw Through a Sickly Lens

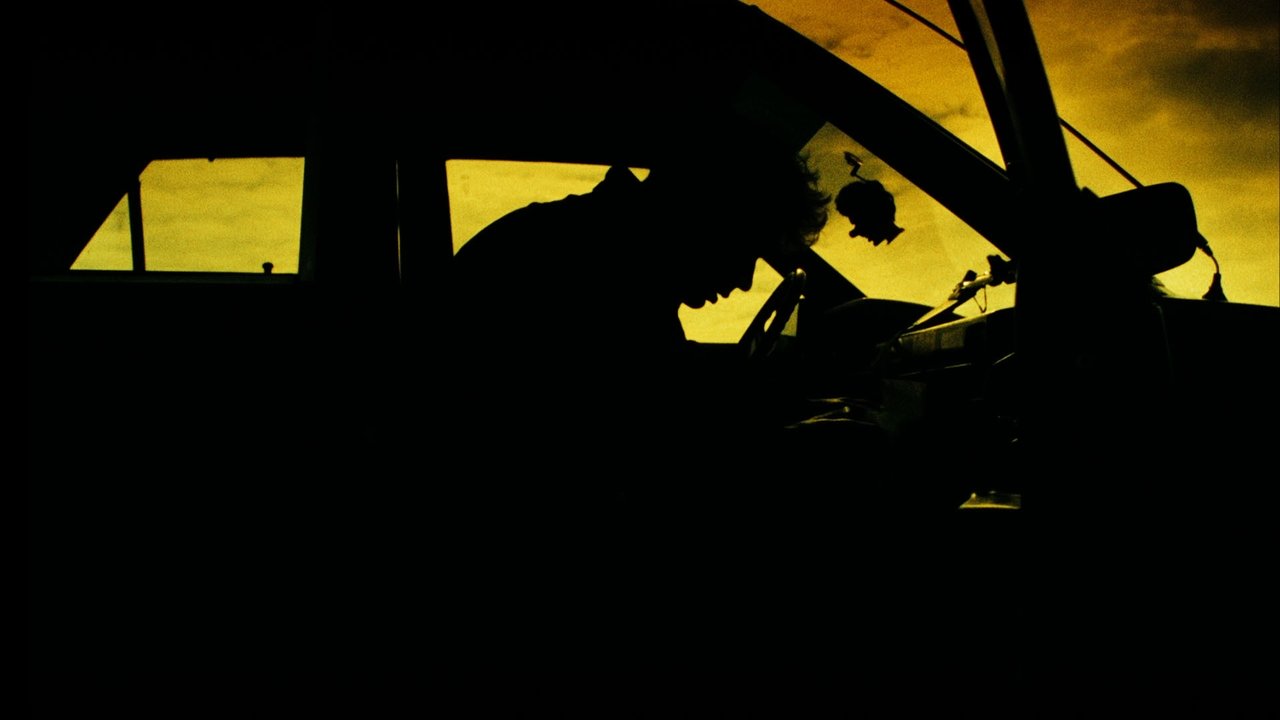

The film’s oppressive atmosphere is as crucial as its narrative. Cinematographer Sławomir Idziak bathes Warsaw in sickly greens and yellows, using heavy filters that drain the life out of the image, mirroring the moral decay and spiritual emptiness at the story's core. Reportedly, Idziak was initially reluctant to shoot such a bleak film and proposed using these experimental, 'ugly' techniques partly hoping Kieślowski might reconsider. Instead, the director embraced the approach, which perfectly captured the grim, desaturated reality he envisioned. This visual choice wasn't just aesthetic; it immerses the viewer in a world devoid of warmth, where hope seems a distant, irrelevant memory. The cityscape itself feels like a participant – indifferent, decaying, complicit in the bleakness unfolding within it.

Portraits of Desperation and Doubt

The performances are central to the film's power. Mirosław Baka is terrifyingly blank as Jacek for much of the film, his violence erupting from a place of deep-seated alienation rather than clear motive. Yet, in his final moments, facing his own death, cracks appear, revealing a pathetic, frightened young man beneath the monstrous act. It’s a chilling portrayal of how violence dehumanizes both victim and perpetrator. Krzysztof Globisz, as Piotr, serves as the audience's surrogate. He begins with a certain faith in the legal system, but witnessing the mechanics of capital punishment firsthand shatters his idealism. His journey is one of profound disillusionment, forcing him (and us) to confront the chilling parallels between Jacek’s crime and the state’s retribution. Jan Tesarz also leaves a mark as the taxi driver, his ordinary life and small cruelties making his sudden, brutal end all the more shocking.

More Than Just a Polemic

While A Short Film About Killing is often cited for its role in reigniting the debate on capital punishment in Poland – indeed, a moratorium was declared shortly after its release – Kieślowski and Piesiewicz insisted their aim was broader: an indictment of killing in all forms. The film deliberately juxtaposes the impulsive, chaotic violence of Jacek with the methodical, sanctioned violence of the state. Does one cancel out the other? Does legal justification make the act itself any less horrifying? Kieślowski offers no easy answers, leaving the viewer grappling with the profound moral weight of the question. He avoids exploring Jacek's backstory in detail, denying us the comfort of easy psychological explanations. The randomness makes the initial crime feel even more terrifying, a rupture in the fabric of everyday life.

One fascinating production tidbit: the sheer intensity of Idziak’s custom-made filters apparently rendered much of the camera equipment unusable after filming. It's a striking metaphor, perhaps, for how deeply the film's corrosive vision permeated its own creation. This wasn't just another movie; it felt like handling something dangerous, something that could stain you.

Lasting Resonance

Watching A Short Film About Killing today, possibly decades after first encountering it on VHS, its power hasn't diminished. It remains a brutal, essential piece of cinema. It doesn't flinch, it doesn't compromise, and it leaves an indelible mark. It lacks the comforting nostalgia often associated with films from this era, but its stark honesty and profound questioning of violence make it unforgettable. It’s a film that reminds us of cinema's power not just to entertain, but to deeply disturb and provoke reflection.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score reflects the film's masterful direction, unforgettable performances, and courageous, unflinching confrontation with its subject matter. The deliberate pacing and oppressive atmosphere are incredibly effective, serving the film's thematic weight. It’s a difficult watch, undeniably, but its artistry and moral seriousness are undeniable, making its bleakness feel earned rather than gratuitous.

It leaves you pondering: what truly separates the killer from the executioner when the end result is the same extinguished life? A question as relevant and troubling now as it was back in 1988.