It doesn't begin with a bang, but with a slow, creeping realization – the sheer, sprawling scale of it all. Watching Steven Soderbergh's Traffic (2000) again, nearly a quarter-century later, feels less like revisiting a movie and more like plunging back into a meticulously documented, deeply unsettling ecosystem. It arrived at the cusp of a new millennium, feeling urgent and vital, a film that wasn't just telling stories, but mapping the insidious connective tissue of the international drug trade. Even now, its power lies not in easy answers, but in the uncomfortable questions it forces us to confront.

A Tangled Web, Visually Defined

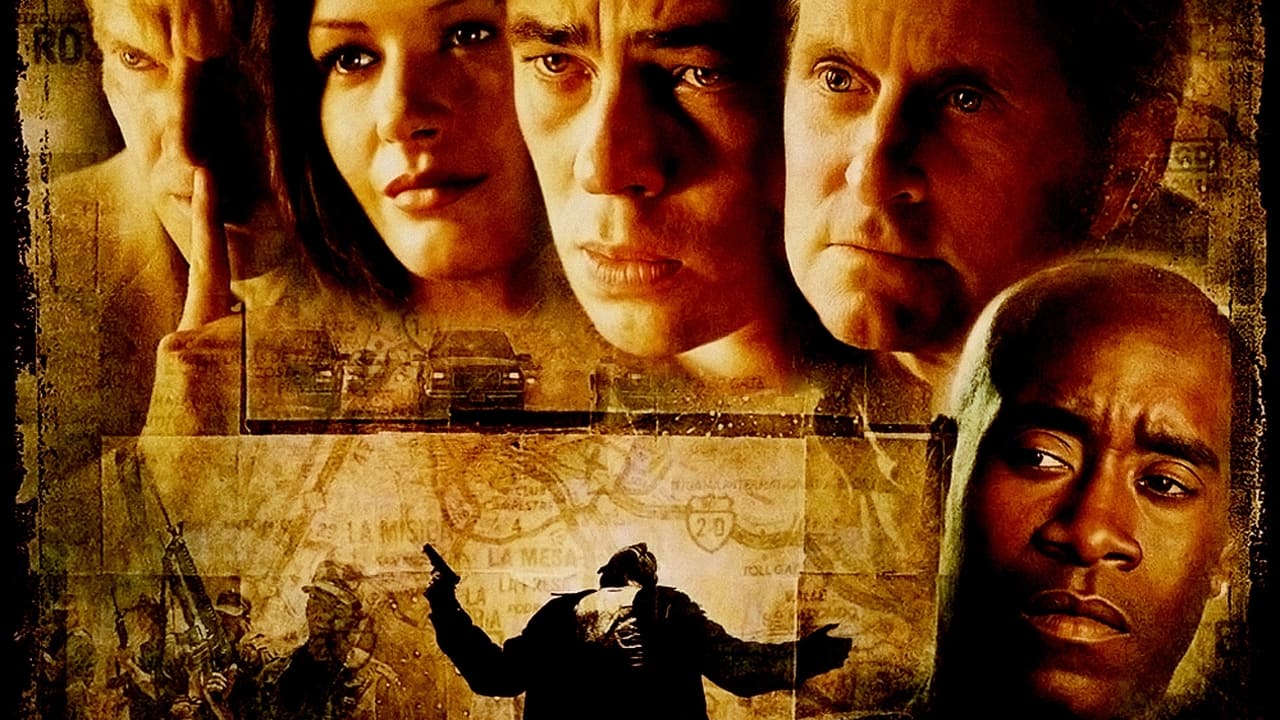

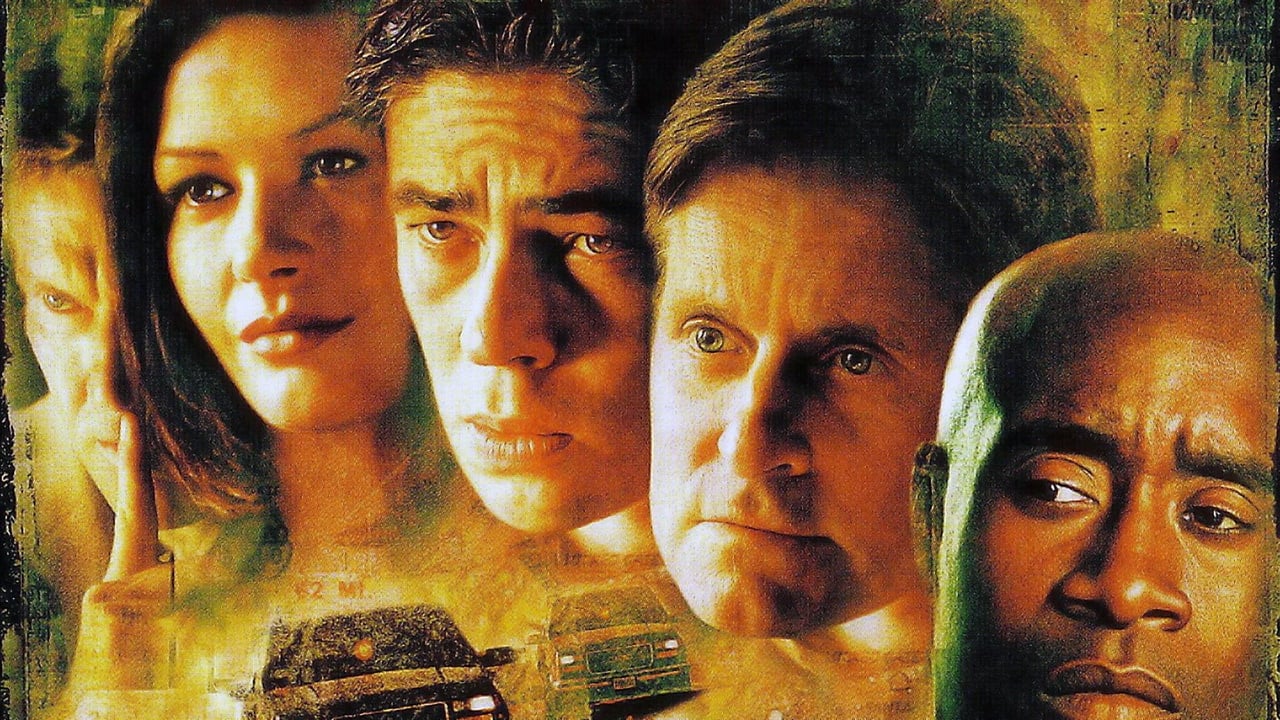

Forget neat, linear narratives. Traffic throws you headfirst into a multi-pronged assault on the senses and the conscience. We follow Robert Wakefield (Michael Douglas), the newly appointed US drug czar discovering the intractable nature of the beast, even as his own daughter spirals into addiction. We're embedded with Mexican state policeman Javier Rodriguez (Benicio del Toro) navigating a treacherous landscape of corruption where loyalty is a currency constantly being devalued. And we witness the chilling transformation of Helena Ayala (Catherine Zeta-Jones), a wealthy San Diego housewife forced to confront the brutal realities of her husband's cartel connections. Woven through these are the tense undercover operations led by DEA agents like Montel Gordon (Don Cheadle).

What binds these disparate threads isn't just the thematic core, but Soderbergh's audacious directorial choices. Famously, he acted as his own cinematographer (under the pseudonym Peter Andrews), employing distinct color palettes for each storyline. The Washington D.C. scenes surrounding Wakefield are bathed in a cold, institutional blue, reflecting the detached bureaucracy grappling with an unwieldy problem. Across the border, Javier's world burns with a gritty, sun-bleached yellow, emphasizing the heat, dust, and moral decay. The Ayala storyline unfolds in sharp, almost hyper-real natural light, stripping away artifice as Helena descends into her husband's dark world. It's not just a gimmick; it’s visual storytelling at its most effective, instantly orienting the viewer within this complex tapestry and subtly coloring our emotional response to each environment.

Performances Forged in Realism

The film hinges on the authenticity of its performances, and the ensemble cast delivers with remarkable nuance. Benicio del Toro, in a largely Spanish-speaking role that rightly earned him an Academy Award, is captivating as Javier. He conveys worlds of weary understanding and simmering conflict with subtle shifts in his eyes and posture. You feel the weight of impossible choices pressing down on him. Michael Douglas portrays Wakefield's journey from confident authority figure to a man hollowed out by helplessness with poignant vulnerability. His final, almost silent realization about the futility of his position is devastating.

Catherine Zeta-Jones, meanwhile, sheds her glamorous image to embody Helena's steely resolve born of desperation. Her transformation from naive socialite to a player in the game is both chilling and utterly believable. And Don Cheadle, alongside his partner Luis Guzmán, brings a grounded intensity to the street-level fight, showcasing the constant danger and moral compromises faced by those on the front lines. Soderbergh encouraged improvisation and fostered a naturalistic style, making the interactions feel less scripted and more observed.

From Miniseries to Millennium Masterpiece

It's worth remembering that Traffic wasn't born solely from Hollywood. Stephen Gaghan's Oscar-winning screenplay was a masterful adaptation of the acclaimed 1989 British Channel 4 miniseries Traffik. Gaghan condensed and recontextualized the sprawling narrative for an American audience, sharpening its focus while retaining its moral complexity. Getting the film made wasn't straightforward; its challenging subject matter and multi-lingual, multi-narrative structure weren't typical blockbuster fare. Harrison Ford reportedly passed on the Wakefield role before Michael Douglas signed on, lending the project significant star power.

Soderbergh, riding high on the success of Erin Brockovich released the same year (a rare double-header of critical and commercial triumph), brought a restless, experimental energy to the production. Filming took place across numerous locations, from the corridors of power in D.C. to the dusty streets of Tijuana and the affluent suburbs of San Diego, adding to the film's expansive feel. Soderbergh’s insistence on using handheld cameras and available light contributed significantly to the documentary-like immediacy. This wasn't a polished Hollywood fantasy; it felt ripped from the headlines, raw and unfiltered. The approach clearly resonated: made for around $46 million, Traffic grossed over $207 million worldwide and became a major awards contender, proving audiences were hungry for complex, adult-oriented drama.

The Unwinnable War?

What lingers most powerfully after watching Traffic is its profound sense of ambiguity. It doesn't offer simple solutions or clear-cut heroes and villains. Instead, it presents a system – vast, interconnected, and deeply entrenched – where individuals are often swept along by forces far larger than themselves. Corruption isn't just a Mexican problem; it seeps into every level. Addiction isn't just a personal failing; it's a symptom of deeper societal issues. The film asks: Is the "war on drugs" winnable? Or is it a self-perpetuating cycle of violence, corruption, and despair? It doesn't preach, but lays bare the human cost from every conceivable angle.

Does it feel dated? Perhaps in some of the technology depicted, but the core issues feel disturbingly relevant. The questions it raised about policy, addiction, and international cooperation are ones we're still grappling with today. It avoids easy moralizing, forcing us instead to sit with the complexity, the compromises, the sheer human messiness of it all.

Rating: 9/10

Traffic earns its high score through its sheer ambition, masterful execution, and unforgettable performances. Soderbergh’s distinctive visual style perfectly serves the intricate narrative, while the cast embodies the human toll of the drug trade with raw authenticity. It avoids easy answers, instead offering a complex, multi-faceted portrait that feels both specific to its turn-of-the-millennium moment and depressingly timeless. It might have hit shelves as VHS tapes were starting to gather dust, transitioning us into the DVD era, but its challenging, intelligent filmmaking felt like a powerful evolution, demanding our attention then and now.

It leaves you not with a sense of closure, but with a heavy heart and a mind racing – the mark of a truly significant film that dared to map the unwinnable war.