Sometimes, amidst the explosion-heavy blockbusters and neon-drenched thrillers that defined so many trips to the video store, you’d stumble upon something quieter. Something unexpected. Tucked away perhaps in the 'World Cinema' section, if your local shop was adventurous enough to have one, was a film like Jafar Panahi's The White Balloon (1995). It didn't shout for attention with its cover art, yet pulling that tape off the shelf felt like uncovering a small, perfectly formed jewel. Its power doesn't lie in spectacle, but in the profound truth found within the simplest of childhood quests.

The premise feels almost impossibly slight: It’s Norouz, the Iranian New Year, and little Razieh (Aida Mohammadkhani) has her heart set on one specific, chubby goldfish to celebrate the occasion. Her mother (Fereshteh Sadre Orafaiy) eventually relents, giving her the family's last 500-toman note. What follows is Razieh's determined, often frustrating journey through the bustling streets of Tehran to buy her fish, a journey where the precious banknote repeatedly slips, quite literally, through her fingers. It sounds mundane, perhaps, but under Panahi's sensitive direction, it becomes a microcosm of life itself – full of fleeting hopes, sudden obstacles, and the kindness (or indifference) of strangers.

A Child's World, Universally Felt

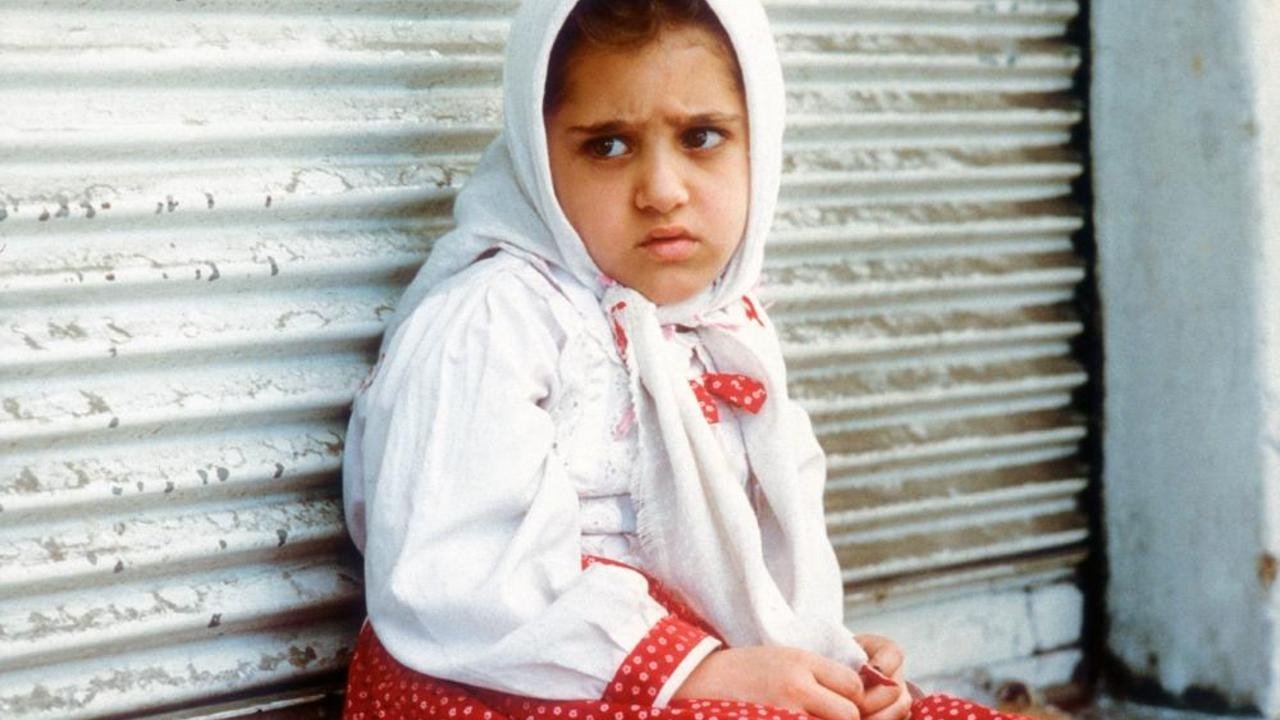

What elevates The White Balloon beyond a mere slice-of-life story is the absolutely captivating performance from young Aida Mohammadkhani. This wasn't a seasoned child actor; Panahi, following in the footsteps of his mentor Abbas Kiarostami (who also penned the screenplay based on a story Panahi recounted from his own youth), cast non-professionals, seeking authenticity above all else. And he found it in spades with Mohammadkhani. Her portrayal of Razieh is utterly devoid of artificiality. We see her stubborn determination, her moments of heartbreaking panic when the money is lost, her flashes of manipulative charm trying to enlist help – it all feels breathtakingly real. You're not just watching a character; you feel you know this little girl, her anxieties becoming your own. Remember that feeling as a kid, when losing a small amount of money felt like the end of the world? This film taps directly into that primal childhood dread and perseverance.

The film unfolds in what feels like real-time, mirroring the urgency Razieh feels as the New Year celebrations approach. Panahi, who previously worked as an assistant director for Kiarostami on films like Through the Olive Trees (1994), demonstrates a remarkable restraint and focus in this, his debut feature. The camera often stays at Razieh's eye level, immersing us completely in her perspective. Tehran isn't just a backdrop; it's a living, breathing entity she must navigate – crowded streets, distracting snake charmers, busy shoppers, and soldiers who barely notice her plight. Each encounter, whether helpful or dismissive, adds another layer to this deceptively simple narrative tapestry.

More Than Just a Fish Story

It’s fascinating how Panahi and Kiarostami generate suspense from such minimal ingredients. There are no villains in the conventional sense, only the everyday hurdles of urban life and the ticking clock. The tension comes from our empathy for Razieh. Will she get the fish? Will someone help her retrieve the money from the sewer grate? These small stakes feel monumental because we are so invested in her small world. It’s a different kind of cinematic thrill than the car chases or shootouts common in other mid-90s VHS staples, but no less gripping in its own quiet way.

Reportedly, filming with a young, non-professional lead navigating chaotic real locations presented its own set of challenges, but the result is a testament to Panahi's patient direction. The film's success wasn't just critical; it won the prestigious Caméra d'Or for best first feature at the 1995 Cannes Film Festival, instantly putting Panahi on the map as a major voice in international cinema. It was a significant moment, signaling the strength and unique perspective of the Iranian New Wave to a wider audience.

The film’s title, The White Balloon, is somewhat symbolic, perhaps representing fleeting desires or innocence (a balloon seller features significantly in the final moments), though the narrative focuses squarely on the coveted goldfish. It’s that tangible goal, the fish swimming in its little bowl, that drives Razieh forward with such single-mindedness.

Lasting Impressions

The White Balloon doesn't offer easy resolutions or grand pronouncements. Its beauty lies in its observation, its gentle portrayal of human interaction, and its profound understanding of childhood emotion. The final shot, lingering on a character often overlooked, is quietly devastating and leaves you pondering themes of community, isolation, and the small acts of kindness that shape our days. What does it say about the world that this child's desperate mission is met with such varied reactions? Doesn't her resilience mirror something fundamental about the human spirit?

Finding this film back then, perhaps nestled between Hollywood fare, felt like a discovery. It reminded us that powerful stories don't always need big budgets or complex plots. Sometimes, all you need is a little girl, a lost banknote, and a deep well of empathy.

Rating: 9/10

Justification: This near-perfect gem earns its high score through its masterful direction, the unforgettable and authentic central performance, its profound simplicity, and its ability to create palpable tension and emotional resonance from the most basic of scenarios. It’s a masterclass in neorealist filmmaking that feels both specific to its time and place, and universally human.

VHS Heaven Final Thought: A quiet masterpiece that reminds you of the weight of small things in a child's world, and the enduring power of simple, honest storytelling – a truly special find on any rental shelf.