The neon glow reflecting off rain-slicked streets, the quiet desperation in a man's eyes – some cinematic atmospheres wrap around you like a shroud. Gary Fleder's 1995 neo-noir thriller, Things to Do in Denver When You're Dead, is precisely that kind of film. It arrived in the wake of Pulp Fiction's seismic impact, inevitably drawing comparisons, yet carved out its own distinct, melancholic groove. This wasn't a movie you stumbled upon easily in the multiplex; this felt like a discovery, a tape passed between friends, whispered about in hushed tones after a late-night viewing that left you feeling decidedly uneasy.

### Giving It a Name

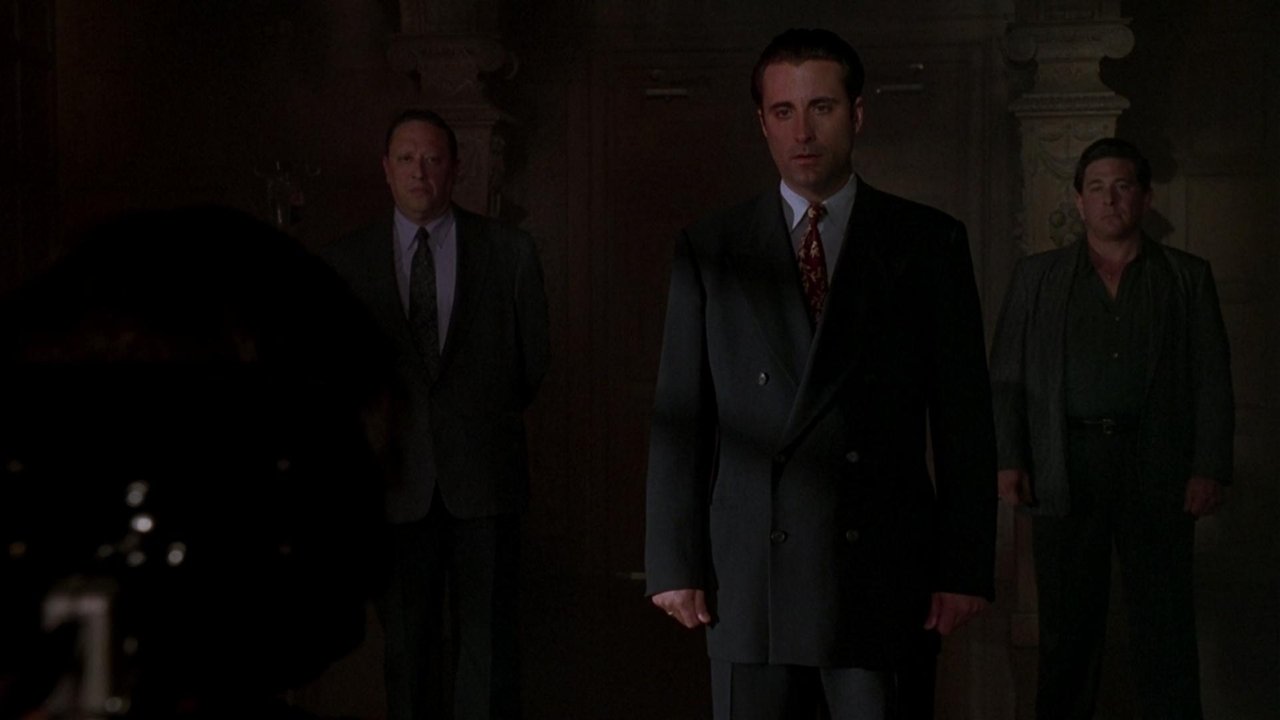

At its core, the film follows Jimmy "The Saint" Tosnia (Andy Garcia, radiating cool desperation), an ex-gangster trying to go straight with his "Afterlife Advice" business – recording final messages for the terminally ill. It's a gig as grimly ironic as Jimmy's eventual fate. Pulled back into the life he tried to leave by his former boss, the chillingly powerful quadriplegic known only as "The Man With The Plan" (Christopher Walken in one of his most unnervingly still performances), Jimmy is tasked with a seemingly simple job: scaring the ex-boyfriend of The Man's disappointing son. Of course, nothing goes according to plan. Jimmy assembles his old crew – Pieces (Christopher Lloyd, wonderfully cast against type), Critical Bill (Treat Williams, simmering with barely contained psychopathy), Franchise (William Forsythe), and Easy Wind (Bill Nunn) – and the job goes spectacularly, tragically wrong. "Buckwheats," as the film's unique, almost poetic slang terms it. Total disaster.

The fallout is swift and merciless. The Man With The Plan gives Jimmy 48 hours to get out of Denver before unleashing the angel of death himself: Mr. Shhh (Steve Buscemi, lean and lethal), a hitman who communicates primarily through the thwip of his silenced pistol. What follows isn't just a standard thriller plot; it's an elegy for lost chances, a meditation on loyalty and the inescapable pull of past mistakes, all wrapped in sharp suits and sharper dialogue penned by Scott Rosenberg. Fun fact: Rosenberg, who would later pen Con Air and Beautiful Girls, reportedly wrote this script while working late nights and sold it relatively cheaply before it gained traction, a testament to the unpredictable journey of cult classics.

### Style Over Slam Dunks

Fleder, making his feature debut, crafts a world drenched in blues and shadows, perfectly capturing the lonely nighttime vibe of a city holding its breath. The score by Michael Convertino underscores the melancholy, a mournful jazz trumpet often punctuating Jimmy's quiet despair. Denver itself becomes a character – not the sunny ski-resort image, but a network of dimly lit bars, pool halls, and anonymous streets where bad things happen under the cover of darkness. It’s a tangible sense of place that grounds the sometimes-stylized violence and dialogue. Remember how certain films just felt like the 90s? This one bottled that specific brand of cool, dark, and slightly dangerous energy perfectly.

The performances are uniformly excellent. Garcia carries the film with understated charisma, his Jimmy a man grappling with the consequences of his choices, trying to salvage something decent – namely, his burgeoning relationship with Dagney (Gabrielle Anwar) – before his time runs out. But it's the supporting cast, particularly the villains, who truly elevate the proceedings. Christopher Walken is mesmerizing. Confined to a wheelchair, his power comes not from physicality but from absolute stillness and measured, terrifying pronouncements delivered in that iconic cadence. His scenes are masterclasses in quiet menace. And then there’s Christopher Lloyd as Pieces, a former mob enforcer ravaged by leprosy, adding a layer of grotesque tragedy that’s hard to shake. It's a far cry from Doc Brown, showcasing Lloyd's incredible range.

### Those Denver Details

The film's unique lexicon ("boat drinks," "buckwheats," giving it "a name") lends it a distinct flavor, feeling less like a Tarantino rip-off and more like its own self-contained universe. This slang wasn't just window dressing; it painted a picture of a coded underworld where euphemisms softened harsh realities, at least until Mr. Shhh showed up. Interestingly, the film's title itself comes from a Warren Zevon song, a connection that perfectly mirrors the movie's blend of gallows humor and existential dread.

Despite its style and stellar cast, Things to Do in Denver When You're Dead famously underperformed at the box office upon release, pulling in just over $500,000 domestically against an estimated $8 million budget. It seemed destined to be forgotten. But then came video. My own well-worn VHS copy, rented countless times from the local store, attests to its second life. This was prime "discover it on the shelf" material. Its blend of dark humor, sudden violence, existential angst, and quotable lines found its audience in the flickering glow of CRT screens, building the cult following it rightly deserved. Doesn't that almost nihilistic ending still pack a punch, even today?

### Final Verdict

Things to Do in Denver When You're Dead isn't a perfect film. The pacing occasionally meanders, and some plot elements feel a touch convenient. However, its strengths – the palpable atmosphere, the razor-sharp dialogue, the unforgettable performances (especially Walken's), and its pervasive sense of stylish melancholy – far outweigh its flaws. It’s a film that captures a specific mid-90s mood, a kind of post-modern noir that feels both dated and timeless. It broods, it charms, and it chills, often in the same scene.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's undeniable cult classic status, exceptional performances, unique atmosphere, and killer dialogue, acknowledging minor pacing issues but celebrating its enduring cool. For fans of 90s crime thrillers with a dark, existential edge, this remains essential viewing – a reminder that sometimes the most memorable journeys end not with a bang, but with the quiet finality of giving it a name. It’s a quintessential piece of VHS Heaven history.