It begins with a feeling, doesn't it? That low hum of anxiety beneath the surface of a city that never truly sleeps. For John LeTour, the protagonist of Paul Schrader's haunting 1992 film Light Sleeper, that hum is the soundtrack to a life lived in the twilight hours, delivering high-end narcotics to Manhattan's affluent clientele. Watching it again recently, perhaps late at night as it demands, I was struck by how acutely the film captures a specific kind of urban loneliness, a feeling that feels both intensely of its early 90s moment and somehow timeless.

Midnight Confessions in a Restless City

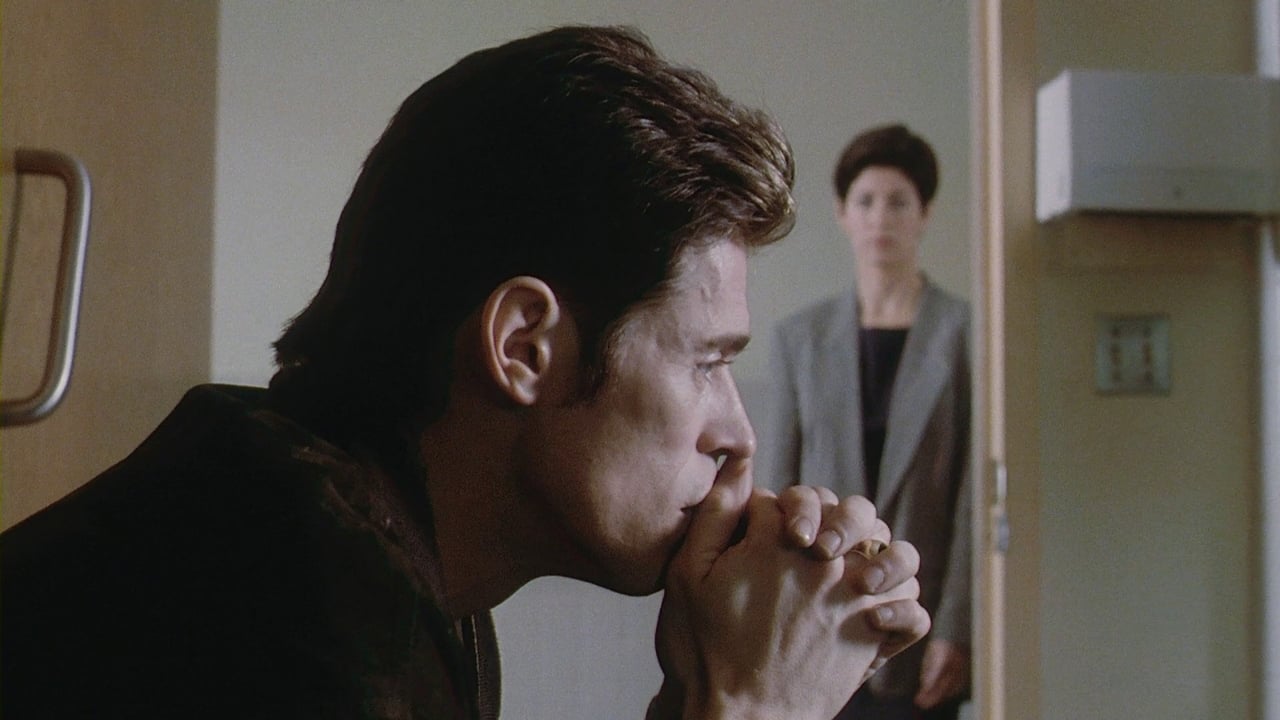

This isn't the explosive, stylized crime narrative some might expect from the writer of Taxi Driver and director of American Gigolo. Instead, Light Sleeper offers something more introspective, almost meditative. It completes what Schrader himself called his "man in a room" trilogy – portraits of isolated men navigating moral gray areas. Here, the man is John LeTour, played with mesmerizing vulnerability by Willem Dafoe. Dafoe embodies LeTour not as a hardened criminal, but as a man adrift, a former user now sober but still tethered to the life, yearning for legitimacy as his elegant boss, Ann (Susan Sarandon), contemplates getting out of the business altogether. His face, often shot in close-up, becomes a canvas reflecting the city's weary soul and his own internal conflict. He writes his anxieties down in a diary, his voiceover guiding us through sleepless nights and uncertain days.

The setting is crucial. Schrader filmed during an actual New York City garbage strike, and the piled-up refuse lining the streets isn't just background dressing; it’s a potent visual metaphor for the moral decay and stagnation LeTour feels trapped within. The city itself feels restless, caught between eras, much like our protagonist. It’s a pre-Giuliani, pre-internet Manhattan, captured with a specific, almost grimy texture that feels incredibly authentic to anyone who remembers that time. This wasn't a multi-million dollar blockbuster; reportedly made for around $5 million, its atmosphere feels earned, observed rather than manufactured.

Faces in the Night

The performances are uniformly excellent, grounded in a compelling realism. Willem Dafoe is simply magnetic. He conveys LeTour’s decency, his quiet desperation, and the flicker of hope that refuses to be extinguished, often with just a glance or a hesitant gesture. It’s a performance of subtle shifts and profound weariness. You believe him when he says he’s looking for a way out, even as circumstances conspire to pull him deeper in.

Susan Sarandon brings a cool, maternal authority to Ann. She’s pragmatic, stylish, and clearly cares for John, but there’s an underlying steeliness required by her profession. Their relationship is complex – employer/employee, surrogate mother/son, fellow travelers in a morally compromised world. Sarandon, ever the pro, navigates these nuances beautifully. Then there's Dana Delany as Marianne, LeTour’s former flame, now clean and living a conventional life. Her reappearance forces John to confront the wreckage of his past and the future he desperately craves but feels unworthy of. Delany imbues Marianne with a fragility and a simmering resentment that makes their encounters charged with unspoken history. Their scenes together are heartbreaking, illustrating the chasm between the life John leads and the one he lost.

Echoes and Choices

Schrader is fascinated by characters hovering on the edge, seeking grace or redemption in unlikely places. LeTour isn't Travis Bickle, consumed by rage, nor Julian Kaye, defined by surfaces. He's quieter, more existentially lost. He consults a psychic, writes in his journal, drifts through the nocturnal city – all attempts to find meaning or direction. The film deliberately avoids easy answers. Is genuine change possible for someone like John? Can you truly escape your past, or are you destined to repeat its patterns?

One fascinating tidbit is the score by Michael Been, lead singer of the rock band The Call. His atmospheric, synth-inflected music perfectly complements the film’s mood – melancholic, searching, and occasionally punctuated by bursts of tension. It avoids typical thriller cues, opting instead for something more ambient and character-driven, much like the film itself.

Schrader has spoken about drawing on his own periods of introspection and uncertainty when writing the film, and that personal resonance bleeds through. It's a film less concerned with plot mechanics (though the narrative does build to a tense climax) than with capturing a state of being. What does it feel like to be forty, working a job with no future, haunted by past mistakes, and sensing that time is running out?

Final Thoughts: A Sleeper Worth Seeking Out

Light Sleeper wasn't a box office sensation upon release, earning perhaps a modest $1 million or so back domestically, but its reputation has deservedly grown over the years, culminating in recognitions like a Criterion Collection release. It's a mature, thoughtful character study masquerading as a crime drama. The deliberate pacing and introspective nature might not be for everyone, especially those seeking high-octane thrills. But for viewers who appreciate nuanced performances, atmospheric filmmaking, and grappling with difficult questions about fate and redemption, it’s a deeply rewarding experience. Watching it on VHS back in the day, probably rented from some corner store shelf long since vanished, felt like uncovering a hidden gem – something quieter and more profound than the usual fare.

Rating: 8/10 - This score reflects the film's powerful atmosphere, Willem Dafoe's exceptional central performance, and Paul Schrader's uncompromising vision. While its deliberate pace might test some viewers, its thematic depth and haunting portrayal of urban alienation make it a standout piece of early 90s independent cinema, fully justifying its place as a cult classic worth rediscovering.

It leaves you contemplating the quiet desperation that can simmer beneath even the most composed surfaces, and the unpredictable ways grace, or perhaps just consequence, can arrive in the dead of night.