The ticking clock is a familiar cinematic device, especially on death row. But in The Chamber, directed by James Foley (Glengarry Glen Ross, At Close Range), that countdown feels less like a race against time and more like a slow, agonizing descent into the dark heart of a family's history. Released in 1996, this adaptation of John Grisham's novel arrived during the peak of his cinematic reign, yet it stands apart – heavier, bleaker, and perhaps more interested in the suffocating weight of the past than the intricacies of legal maneuvering.

Facing the Ghosts of Mississippi

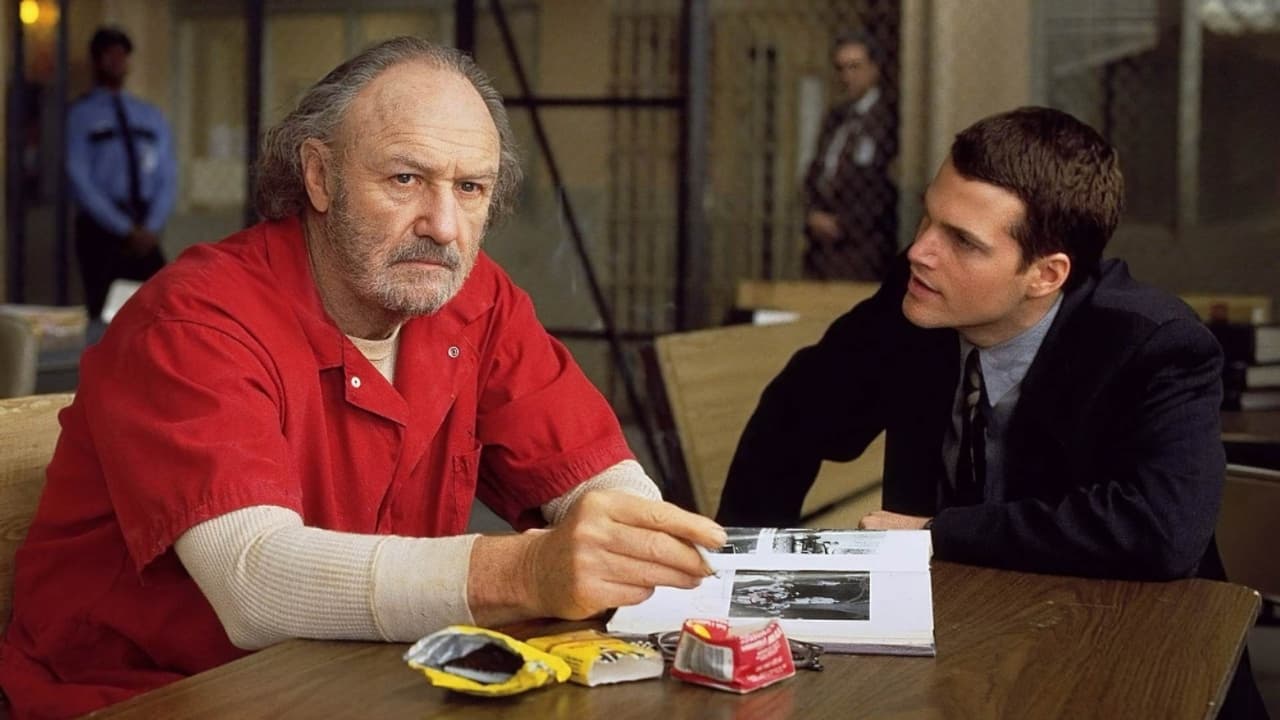

The premise itself is loaded: idealistic young lawyer Adam Hall (Chris O'Donnell) takes on the seemingly impossible task of saving his estranged grandfather, Sam Cayhall (Gene Hackman), from execution. Sam, a notorious Ku Klux Klansman, is just weeks away from paying the ultimate price for a deadly bombing committed decades earlier. Adam isn't just fighting the legal system; he's confronting the poisoned roots of his own family tree, navigating the wary skepticism of his aunt Lee (Faye Dunaway), who carries her own scars from Sam's legacy.

What unfolds isn't a typical courtroom thriller packed with shocking reveals and last-minute evidence. Instead, The Chamber is primarily a character study, using the sterile confines of the Mississippi State Penitentiary (the infamous Parchman Farm, where parts of the film were actually shot) as a crucible. The real drama plays out in the tense, uncomfortable meetings between grandson and grandfather, separated by thick glass but bound by blood and buried secrets. It asks profound questions: Can someone truly change? Does proximity to evil inevitably taint? What responsibility do we bear for the sins of our forefathers?

A Towering, Unflinching Performance

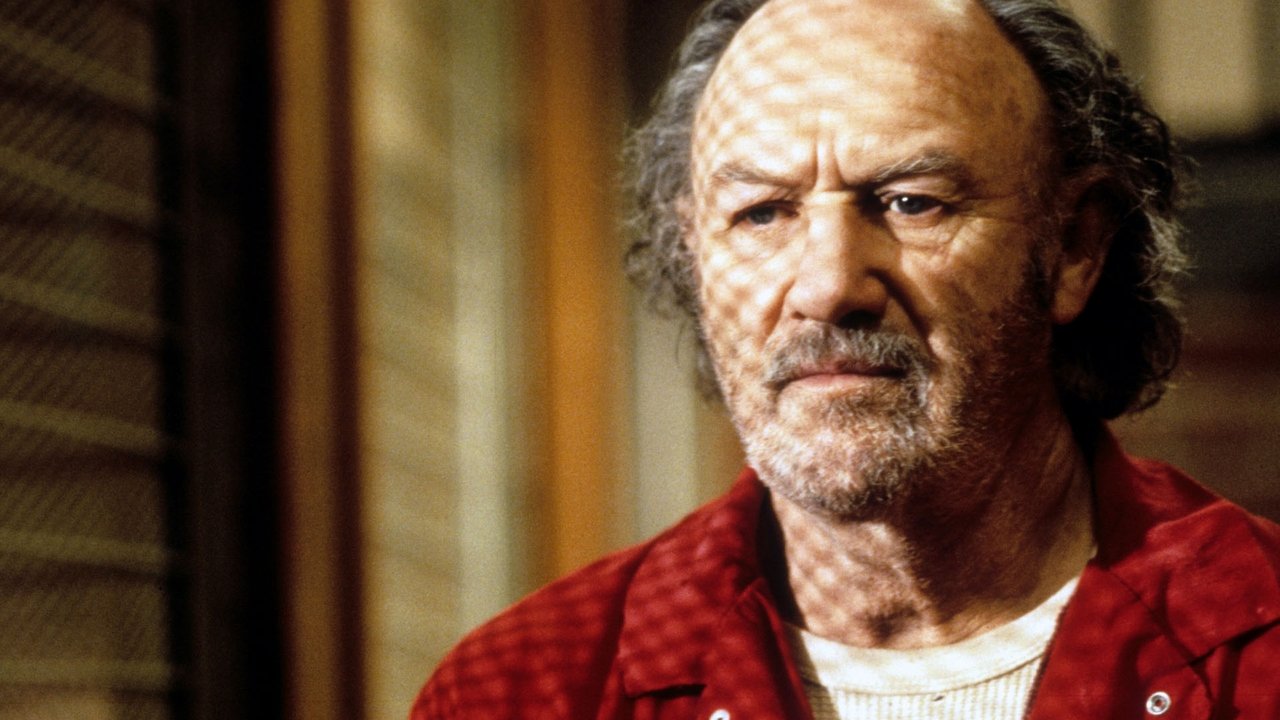

While Chris O'Donnell, then riding high on his Robin fame from Batman Forever (1995), brings a necessary earnestness and youthful drive to Adam, the film belongs unequivocally to Gene Hackman. His portrayal of Sam Cayhall is a masterclass in controlled intensity. Hackman refuses to soften Sam's monstrous bigotry or offer easy redemption. He embodies the character's ingrained hatred with chilling conviction, yet allows fleeting glimpses of vulnerability, regret, or perhaps just weary resignation to flicker beneath the surface as the end draws near. It's a performance that doesn't ask for sympathy but demands attention, forcing us to grapple with the uncomfortable humanity within the monster. It’s the raw power of Hackman’s work here that lingers long after the tape ejects. Faye Dunaway, too, adds a layer of weary grace and deep-seated pain as Lee, a woman caught between familial loyalty and moral revulsion.

Grisham on Screen, But Darker

Adapting Grisham's dense 1994 novel was a formidable task, even with screenwriting royalty William Goldman (All the President's Men, The Princess Bride) credited alongside Chris Reese. Grisham himself reportedly expressed dissatisfaction with the final film, feeling it perhaps strayed too far or simplified the complexities of his narrative. It's fascinating to consider what might have been, as Ron Howard was initially attached to direct, potentially bringing a different sensibility. The film we got, under Foley's direction, leans into the oppressive atmosphere. The Mississippi heat feels almost palpable, the air thick with unspoken history and impending doom. This deliberate pacing and somber tone might be why The Chamber didn't achieve the blockbuster status of The Firm (1993) or The Pelican Brief (1993), grossing a relatively modest $22.5 million against its estimated $50 million budget. It was a tougher, less crowd-pleasing story.

I remember renting this one from Blockbuster, probably nestled right between those other Grisham hits on the shelf. But The Chamber felt different even then. It lacked the propulsive thrills, opting instead for a slow burn that burrowed under your skin. Watching it now, that deliberate pacing feels less like a flaw and more like a conscious choice, mirroring the slow crawl towards Sam's execution date and Adam's painful excavation of the past.

The Weight of Legacy

The Chamber isn't a perfect film. Its focus on character sometimes comes at the expense of narrative momentum, and some of the legal aspects feel underdeveloped compared to its Grisham brethren. Yet, its unflinching look at the corrosive nature of hate, the complexities of family, and the moral quagmire of capital punishment gives it a haunting resonance. Hackman's unforgettable performance elevates the material significantly, grounding the weighty themes in a portrayal that is both terrifying and tragically human. It doesn’t offer easy answers, leaving the viewer in a contemplative, slightly unsettled space.

Rating: 7/10

Justification: While the pacing can be sluggish and it doesn't quite reach the narrative heights of the best Grisham adaptations, The Chamber is anchored by a phenomenal, Oscar-worthy performance from Gene Hackman. Its heavy atmosphere, thoughtful exploration of difficult themes, and refusal to offer easy resolutions make it a memorable, if somber, piece of 90s cinema. It’s a film that sits with you, prompting reflection rather than simple entertainment.

It remains a potent reminder that some chambers – whether cells on death row or the hidden recesses of family history – hold secrets far darker than we might care to admit.