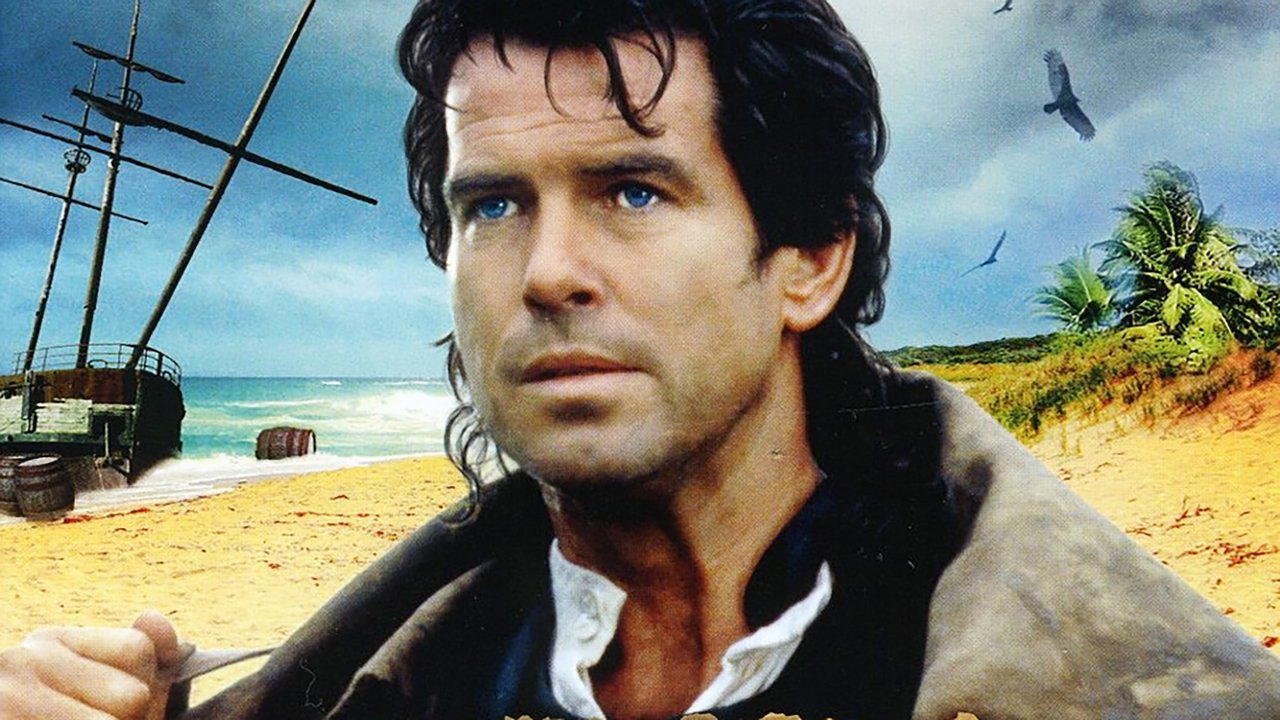

It’s 1997. You stroll down the aisles of Blockbuster, the familiar scent of plastic tape cases and slightly stale popcorn in the air. Pierce Brosnan’s face stares out from countless covers – suave, tuxedoed, unmistakably Bond in GoldenEye and the newly released Tomorrow Never Dies. Then you spot another cover, jarringly different: Brosnan, bearded, ragged, looking decidedly less shaken or stirred on a tropical shore. This was Robinson Crusoe, a film that landed with a curious thud amidst its star's global espionage superstardom, offering a starkly different kind of survival narrative. Seeing 007 himself battling the elements instead of megalomaniacs felt almost like discovering a secret, less-polished mission briefing tucked away on the rental shelf.

Beyond Bondage: A Grittier Island

Based, of course, on Daniel Defoe's seminal 1719 novel, this adaptation, credited to directors George T. Miller (of The Man from Snowy River fame, though perhaps less illustriously, The NeverEnding Story II) and Rod Hardy (a prolific TV director who also helmed the cult creature feature Thirst back in '79), attempts a more grounded, psychologically focused take than many previous versions. The story is familiar: Crusoe, a Scottish gentleman whose pride and wanderlust lead him disastrously to sea, finds himself the sole survivor of a shipwreck, washed ashore on an apparently deserted island. The film jettisons some of the novel’s earlier adventures and focuses almost entirely on the island ordeal, charting Crusoe’s descent into isolation and his eventual, complex relationship with the man he names Friday.

What immediately strikes you watching it now, especially through the lens of VHS nostalgia, is the earnest attempt at grit. The shipwreck sequence feels suitably chaotic for its time, and Crusoe’s initial struggle for survival – building shelter, finding food, battling despair – carries a tangible weight. This isn't the often-sanitized adventure yarn; there's a loneliness here, a palpable sense of Crusoe grappling with his own arrogance and his insignificance against the vast indifference of nature.

The Man Who Would Be King (of an Empty Island)

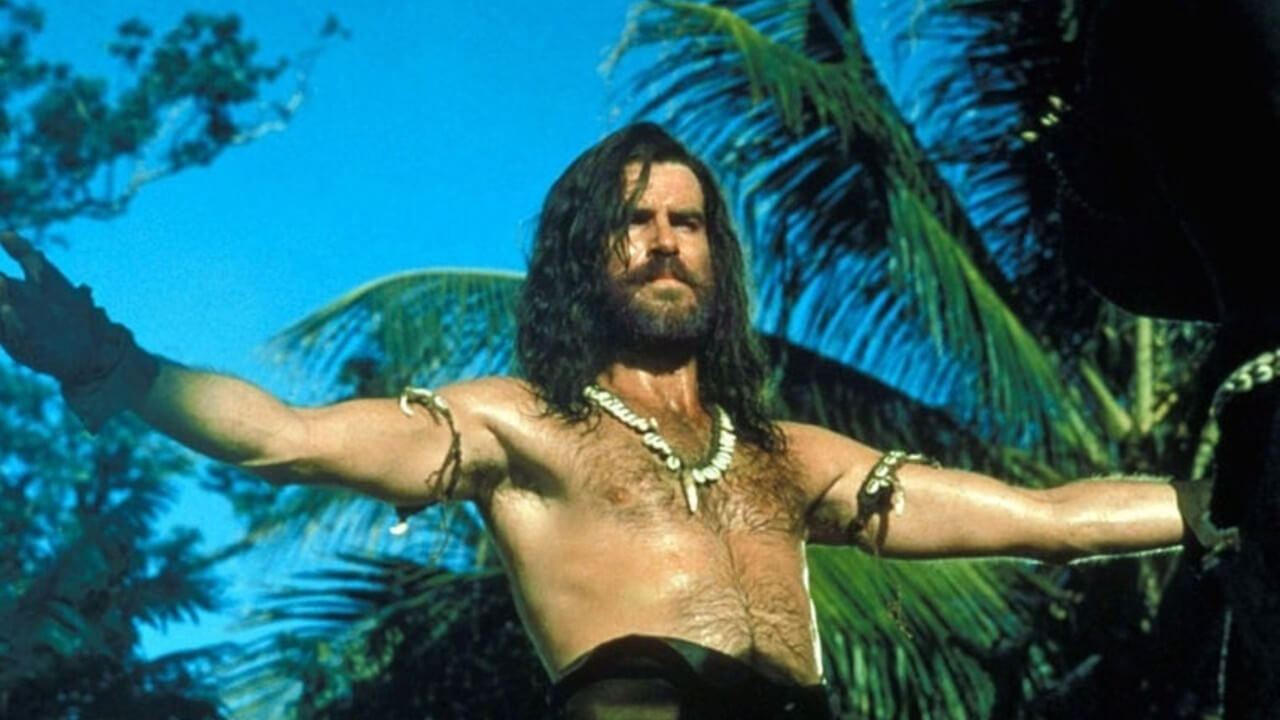

Seeing Pierce Brosnan navigate this landscape is fascinating. Fresh off redefining Bond for the 90s, he clearly throws himself into the physicality of the role. The beard grows, the clothes tatter, and he works hard to convey Crusoe's fraying sanity and eventual resourcefulness. Yet, there's an undeniable friction. Brosnan's inherent charm and almost effortless charisma, so effective as Bond, sometimes feel at odds with the character's intended raw desperation. Can James Bond truly look that convincingly broken? It’s a commendable effort, and he certainly anchors the film, but you occasionally glimpse the sophisticated spy beneath the sun-baked grime, a reminder of the star power that likely got this particular adaptation greenlit. Reportedly made for around $20 million, it didn't make major waves theatrically, becoming more of a video store staple – a curio for Brosnan fans rather than a definitive Crusoe.

Finding Friday, Finding Humanity

Where the film truly finds its footing, however, is in the relationship between Crusoe and Friday. William Takaku, a Papua New Guinean actor performing in his native land (parts of the film were shot there, lending welcome authenticity), brings a quiet dignity and intelligence to Friday that elevates the entire narrative. Their initial encounters are fraught with the expected tension and misunderstanding, reflecting the novel's colonial undertones. Crusoe assumes mastery, imposing his language and beliefs. Yet, Takaku’s performance ensures Friday is never merely a subservient figure. He possesses his own agency, skills, and perspective.

The film wisely centers on their evolving dynamic – from master and captive to tentative allies, and finally, to something resembling genuine friendship and mutual respect. It’s in their shared moments, learning from each other and facing external threats together, that the film resonates most deeply. Takaku’s understated portrayal is the perfect counterpoint to Brosnan's more externally expressed performance, creating a compelling core. Tragically, William Takaku passed away in 2011, making his significant contribution here all the more poignant to revisit.

Navigating Production Shoals

The dual director credit often hints at behind-the-scenes turbulence, and reports suggest George T. Miller departed the project, with Rod Hardy stepping in to complete it. While the final film doesn't feel glaringly disjointed, this change might contribute to a certain unevenness in tone – moments of stark survival drama interspersed with more conventional adventure beats. The production likely faced considerable challenges filming on location in Papua New Guinea, battling the elements in a way that perhaps mirrored Crusoe's own struggles. The practical effects and overall aesthetic firmly plant it in the mid-90s – competent, but lacking the visual flair that might have made it truly timeless. Still, there’s an undeniable appeal to its tangible world, a far cry from the sterile CGI landscapes that would soon dominate adventure films.

Washed Ashore in Memory

Revisiting Robinson Crusoe (1997) today feels like uncovering a slightly faded photograph. It's an earnest, often engaging attempt to wrestle with a complex classic, anchored by committed performances, particularly from the late William Takaku. Brosnan gives it his all, even if his Bond persona casts a long shadow. It doesn't entirely escape the problematic aspects of the source material, but it tries to navigate them with a 90s sensibility, focusing on the human connection that blossoms against all odds. It lacks the iconic status of other Crusoe adaptations or Brosnan's own blockbusters, but as a piece of 90s cinema – the kind of film you'd rent on a whim, intrigued by the star and the promise of adventure – it holds a certain nostalgic charm.

Rating: 6/10

Justification: The film scores points for its earnest attempt at a grittier take, the crucial and affecting performance by William Takaku, and Brosnan's dedicated (if slightly mismatched) effort. The authentic locations add value. However, it's held back by a somewhat uneven tone possibly linked to production issues, a pace that occasionally drags, and the inherent difficulty of fully escaping Brosnan's established screen persona at the time. It’s a solid, watchable adaptation, but not a definitive one.

Final Thought: More than just a footnote in Brosnan's Bond years, this Crusoe remains a thoughtful, if imperfect, exploration of isolation and connection, carried by the quiet power of the bond forged between two men adrift from their respective worlds – a theme that still resonates long after the VCR has whirred to a stop.