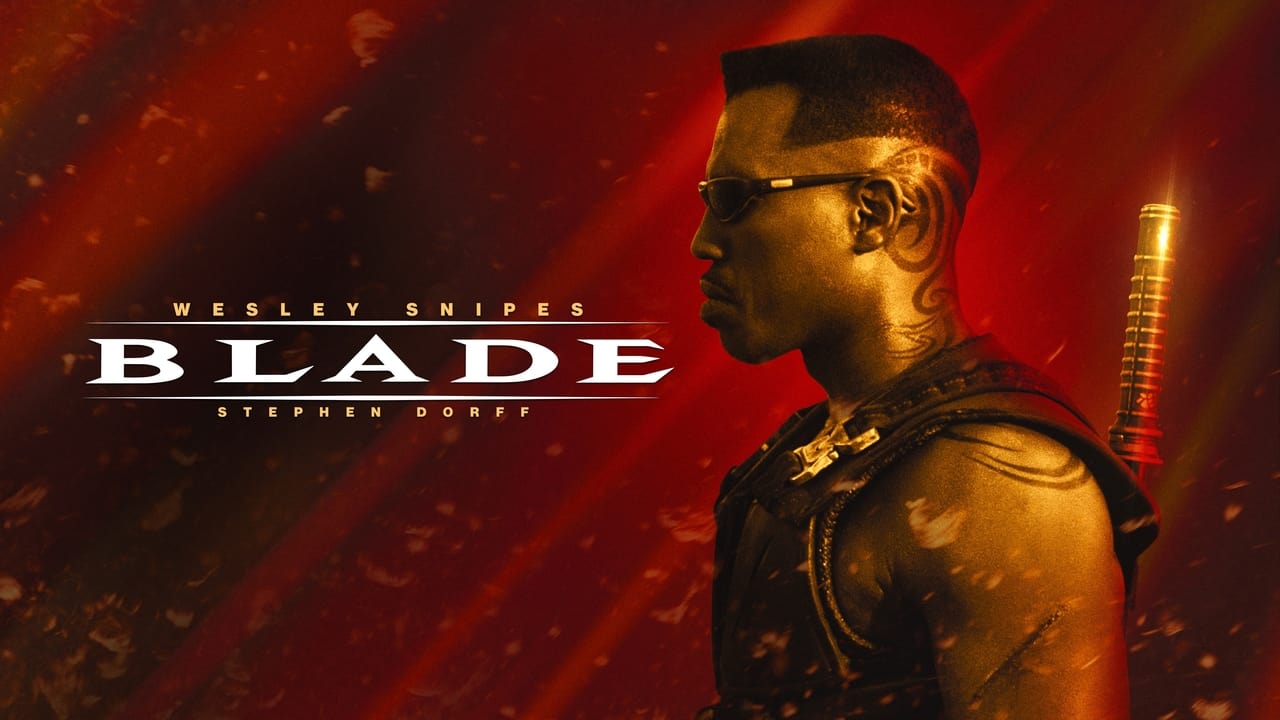

Forget the spandex parade and the shared universes for a moment. Cast your mind back to 1998, a time when the idea of a truly dark, R-rated superhero film felt like a dangerous rumour whispered in the back alleys of comic shops. Then, slicing through the neon-drenched optimism of the late 90s, came Blade. This wasn't just another adaptation; it felt raw, visceral, beamed straight from the gritty pages of a forgotten Marvel horror title onto our buzzing CRT screens. It landed with the force of a silver stake to the chest, dragging comic book movies out of the brightly coloured light and deep into the shadows where they arguably found a new, dangerous pulse.

### The Daywalker Cometh

At the dead centre of this maelstrom is Wesley Snipes (Demolition Man, New Jack City) as the titular character, and let's be blunt: has there ever been a more perfect fusion of actor and comic book role in that era? Snipes is Blade. It’s not just the imposing physique or the stoic delivery; it’s the coiled intensity, the lethal grace of his movements honed by his own extensive martial arts background. He embodies the Daywalker's eternal conflict – half-human, half-vampire, tormented by the thirst but driven by vengeance. Every glare, every swift, brutal dispatch feels utterly authentic. This wasn't just an actor playing dress-up; it felt like watching a force of nature unleashed. Reportedly, Snipes was so immersed in the role, staying in character even off-camera, that it sometimes created friction but undeniably contributed to the film's focused intensity. It’s a performance that anchors the film in a terrifying reality, even amidst the supernatural carnage.

### Bathed in Blood and Techno

Director Stephen Norrington, though his subsequent career proved unfortunately short (The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen being his troubled follow-up), crafts an undeniable atmosphere here. Blade practically drips with late-90s industrial cool. The colour palette is dominated by cold blues, stark blacks, and sudden bursts of crimson. Combine this with a relentless techno/electronica soundtrack – that iconic blood rave scene set to Pump Panel's remix of New Order's "Confusion" is seared into memory, isn't it? – and you get a film that feels dangerous. The production design paints a world hidden just beneath ours, one of decadent vampire nightclubs pulsating with menace and grimy backstreets where death awaits. It captured a specific, pre-millennium anxiety, a sense that society's glittering surface hid something rotten underneath. This wasn't Bram Stoker's dusty castles; this was urban decay infested with creatures far more predatory than any street gang.

### A Different Breed of Villain

Facing Blade is Deacon Frost, played with sneering, charismatic menace by Stephen Dorff (True Detective Season 3). Frost isn't your traditional ancient vampire lord; he's a young, ambitious upstart, chafing against the old guard's traditions. He represents a modern, nihilistic evil, viewing humans as cattle and the established vampire hierarchy as archaic bores. Dorff injects Frost with a volatile energy that makes him a compelling counterpoint to Blade's stoicism. Supporting them both is the grizzled Kris Kristofferson (Convoy, A Star Is Born '76) as Whistler, Blade's mentor and weaponsmith. Kristofferson brings a world-weary gravitas to the role, grounding the fantastical elements with gruff humanity. Interestingly, Whistler was a character created specifically for the film by writer David S. Goyer (The Dark Knight trilogy), but proved so popular he was later incorporated into the Marvel comics canon – a testament to the film's impact.

### Sharp Edges and Practical Gore

For its $45 million budget (roughly $80 million today), Blade delivered astonishing action and effects for its time. While some of the CGI, particularly in the original, somewhat messy finale involving a swirling 'blood god' Frost (which was famously reworked after poor test screenings into the more straightforward sword fight we know), shows its age, the practical effects largely hold up. The vampire disintegration effect – that rapid burn to skeletal dust – became instantly iconic. The fight choreography is brutal and impactful, showcasing Snipes' skills. Remember the visceral thrill of seeing those silver stakes and UV grenades put to work? It felt genuinely inventive and satisfyingly gory, pushing the R-rating with confidence. New Line Cinema took a significant gamble on this – a relatively obscure Black comic character in a dark, violent adaptation – but it paid off handsomely, pulling in over $131 million worldwide and proving audiences were hungry for something edgier.

### Legacy in Leather

It's hard to overstate Blade's significance. Arriving a couple of years before X-Men (2000) and four years before Spider-Man (2002), it demonstrated that comic book adaptations could be serious, adult-oriented, and commercially successful. Its darker tone, R-rating, and focus on stylish action arguably paved the way for films like The Matrix (released the following year) and the subsequent wave of more mature superhero cinema. Goyer's script treated the source material with respect but wasn't afraid to update it for a modern audience, a template many later films would follow. It wasn't just a hit; it was a proof of concept that resonated through Hollywood. Even though the franchise would continue with Blade II (helmed by Guillermo del Toro) and Blade: Trinity (also written and directed by Goyer, with decidedly mixed results), the impact of this first electrifying entry remains undeniable.

---

VHS Heaven Rating: 9/10

Justification: Blade earns this high score for its groundbreaking impact on the comic book genre, Wesley Snipes' iconic and defining performance, its potent mix of stylish action and horror atmosphere, and its unapologetically dark and R-rated tone that felt revolutionary in 1998. While some CGI elements haven't aged perfectly and the plot is straightforward action-horror fare, the film's energy, visual flair, practical effects, and cultural significance make it a cornerstone of late-90s genre cinema. It proved that superheroes didn't have to be bright and chipper, opening the door for a darker, more complex era.

Final Thought: Pop this tape in (or stream it, if you must), turn down the lights, and appreciate the film that reminded everyone how much bite comic book movies could truly have. It still feels dangerously cool.