How do you reconcile the sublime with the savage? It’s a question that hangs heavy in the air long after the credits roll on Werner Herzog’s staggering 1999 documentary, My Best Fiend (German: Mein liebster Feind - Klaus Kinski). This isn't your typical behind-the-scenes featurette; it's a deeply personal, often harrowing, yet strangely affectionate autopsy of one of cinema's most notoriously volatile and undeniably fruitful artistic partnerships: Herzog's own relationship with the incandescently talented, terrifyingly unpredictable actor, Klaus Kinski. Watching it feels less like viewing a film and more like bearing witness to an exorcism, albeit one conducted with Herzog's signature blend of calm observation and profound, almost poetic insight.

The Volcano and the Observer

At its core, My Best Fiend attempts the seemingly impossible: to understand Klaus Kinski. Herzog, our guide, speaks directly to the camera, his measured Bavarian tones a stark contrast to the volcanic eruptions of Kinski we see in archive footage. He revisits the Peruvian jungles where they shot Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982), the sets of Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), and the very apartment where a young Herzog first encountered the whirlwind that was Kinski. There's no sensationalism in Herzog's narration, even when recounting Kinski's legendary tantrums – the screaming fits, the threats, the moments of near-total chaos. Instead, there's a sense of bewildered grappling, a director still trying to fathom the elemental force he somehow harnessed across five films.

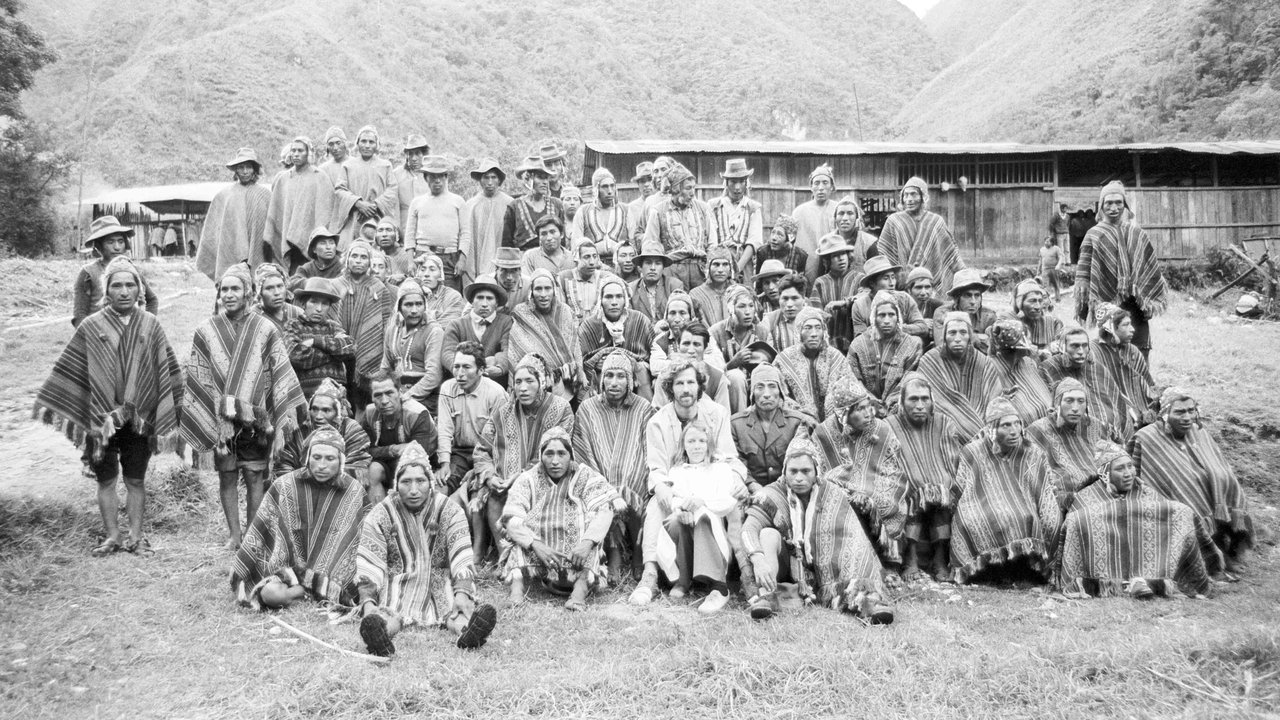

Herzog doesn't shy away from the darkness. We hear the infamous story of Kinski threatening to abandon Aguirre mid-shoot in the remote jungle, prompting Herzog to calmly state he had a rifle and would put eight bullets into Kinski before turning the last on himself. Kinski, Herzog notes with a characteristic deadpan, understood the seriousness of the threat and stayed. It’s a chilling anecdote, but presented not as macho posturing, but as a stark illustration of the extreme measures required to simply keep Kinski working. We even hear from indigenous extras on Fitzcarraldo who, deeply disturbed by Kinski’s abusive behavior towards the crew, genuinely offered to kill the actor for Herzog – an offer the director politely declined. These aren't just gossipy tidbits; they illuminate the near-impossible conditions under which masterpieces were somehow forged.

Beyond the Rages: Glimmers of Humanity?

Yet, My Best Fiend is far more nuanced than a simple catalogue of an actor's monstrous behavior. Herzog seems compelled to find the humanity buried beneath the fury. He shares footage of Kinski playing gently with a butterfly, a moment of quiet tenderness utterly at odds with his terrifying public persona. He interviews Claudia Cardinale, Kinski’s co-star in Fitzcarraldo, who speaks of a different, gentler side she occasionally witnessed. Herzog revisits the Berlin apartment Kinski inhabited during his struggling early years, painting a picture of a man capable of great sensitivity and charm when the mood struck him.

Was this sensitivity genuine, or just another facet of a complex performance? The film doesn't offer easy answers. Herzog acknowledges the profound difficulty, the emotional cost, the sheer danger of working with Kinski. Yet, there's an undeniable undercurrent of respect, even love. Herzog seems to recognize that Kinski's untamed energy, the very quality that made him so impossible, was also the source of his electrifying screen presence. Could the controlled, almost somnambulistic intensity of Nosferatu or the megalomaniacal fire of Aguirre have been achieved by a more 'stable' actor? Herzog seems to doubt it. He needed Kinski, the "best fiend," to realize his visions, even if it nearly broke him each time.

A Testament Forged in Fire

Watching this documentary now, decades after Kinski’s death in 1991, feels poignant. It’s a look back at a kind of filmmaking – perilous, ambitious, personality-driven – that feels increasingly rare. The practical challenges faced on films like Aguirre and Fitzcarraldo, filmed deep in unforgiving locations long before the advent of digital safety nets, are mind-boggling. My Best Fiend serves as a testament not only to Kinski's explosive talent but also to Herzog's unwavering, almost obsessive dedication to his art. It raises profound questions: What is the relationship between genius and madness? What price is too high for great art? Does the finished masterpiece justify the human cost of its creation?

Herzog doesn't flinch from these questions, nor does he provide comforting resolutions. The film exists in that uncomfortable space between admiration and revulsion, between creative necessity and personal torment. It’s a portrait drawn with honesty, complexity, and a strange, lingering affection that feels utterly earned. I remember seeing clips of Kinski's infamous talk show meltdowns back in the day, thinking he was simply unhinged. Herzog’s film doesn’t excuse the behavior, but it contextualizes it within a symbiotic, albeit deeply dysfunctional, creative bond that produced some truly unforgettable cinema.

Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects the film's power as a uniquely intimate and insightful documentary portrait. Herzog masterfully balances the shocking anecdotes with moments of surprising tenderness and profound reflection, offering an unparalleled look into a legendary, terrifying, and creatively vital partnership. It avoids simple hagiography or condemnation, instead presenting a complex, troubling, and utterly compelling human story that deepens our understanding of both men and the extraordinary films they made together.

My Best Fiend leaves you contemplating the ferocious, unpredictable nature of raw talent and the equally fierce determination required to capture it on film. What lingers most is the enigma of that bond – a relationship built on mutual need, profound frustration, and a shared, uncompromising artistic vision that somehow, against all odds, burned brightly enough to leave an indelible mark on cinematic history.