Sometimes a film doesn't grab you by the collar; it invites you to sit beside it in silence, simply to observe the quiet fallout after the storm. Shinji Aoyama's Eureka (2000) is such a film. Clocking in at nearly three-and-a-half hours and presented almost entirely in a stark, sepia-toned monochrome, it arrived just as the new millennium dawned, feeling less like a product of its time and more like a haunting echo from a parallel cinematic universe. Finding this one tucked away in the "World Cinema" aisle of a well-stocked video store back in the day felt like uncovering a secret – a demanding, deeply affecting secret.

After the Unthinkable

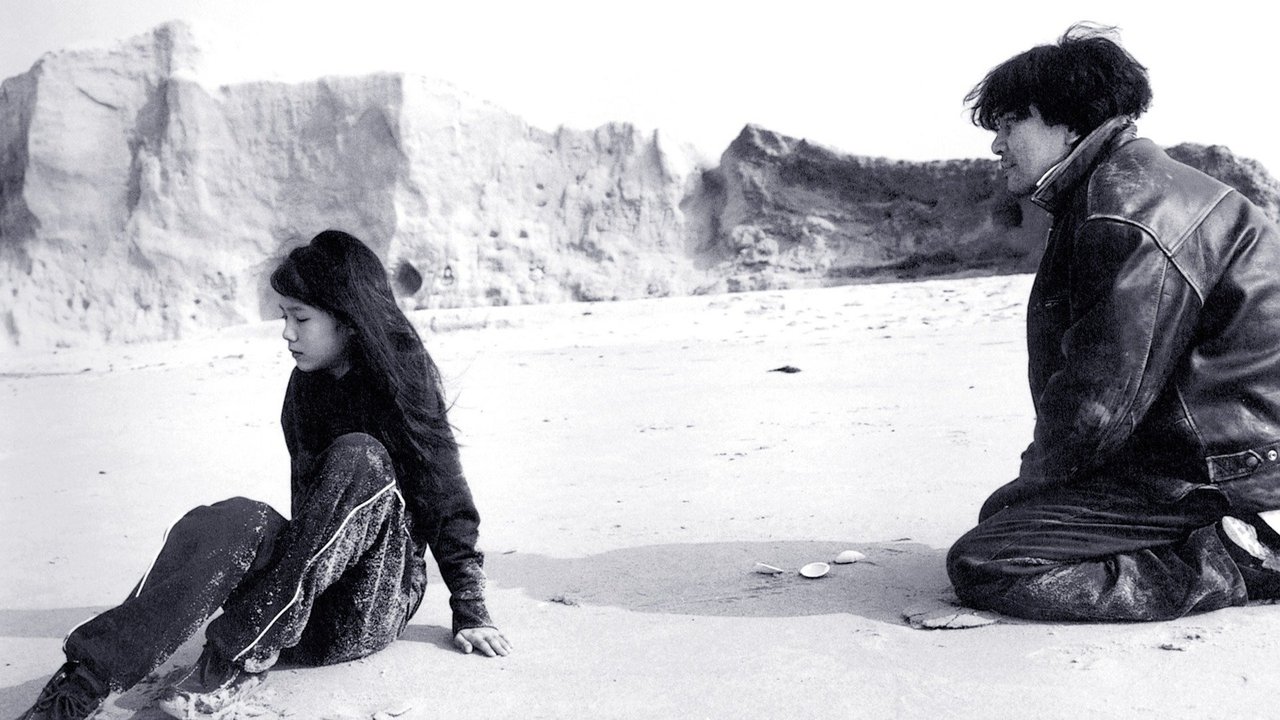

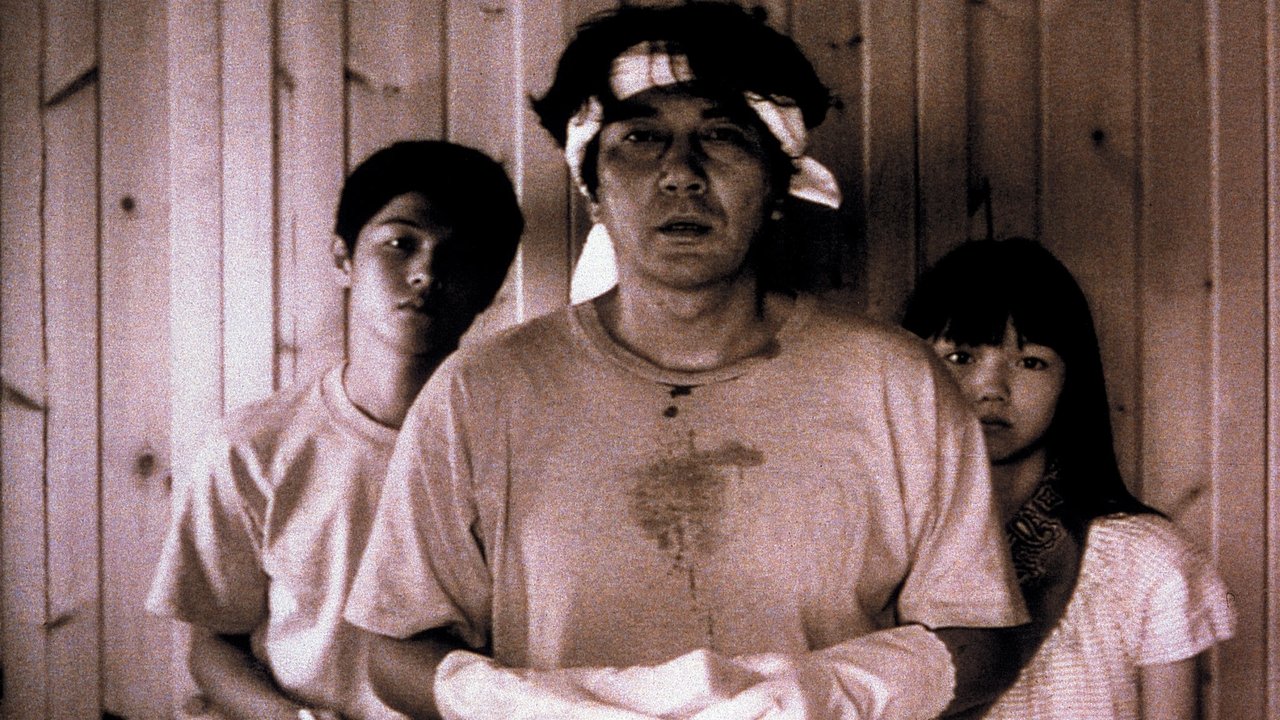

The premise is chillingly simple, yet its tendrils reach deep. A local bus in rural Kyushu, Japan, is hijacked. Only three people survive the ensuing violence: the driver, Makoto Sawai (Koji Yakusho), and two young siblings, Kozue (Aoi Miyazaki) and her older brother Naoki (Masaru Miyazaki, Aoi's real-life brother). The film picks up two years later, finding them irrevocably altered. Sawai is adrift, estranged from his family, a ghost haunting his own life. The children are effectively mute, living in a shell-shocked silence that permeates their once-familiar home. Eureka isn't about the hijacking itself – we see precious little of it – but about the vast, echoing emptiness left in its wake.

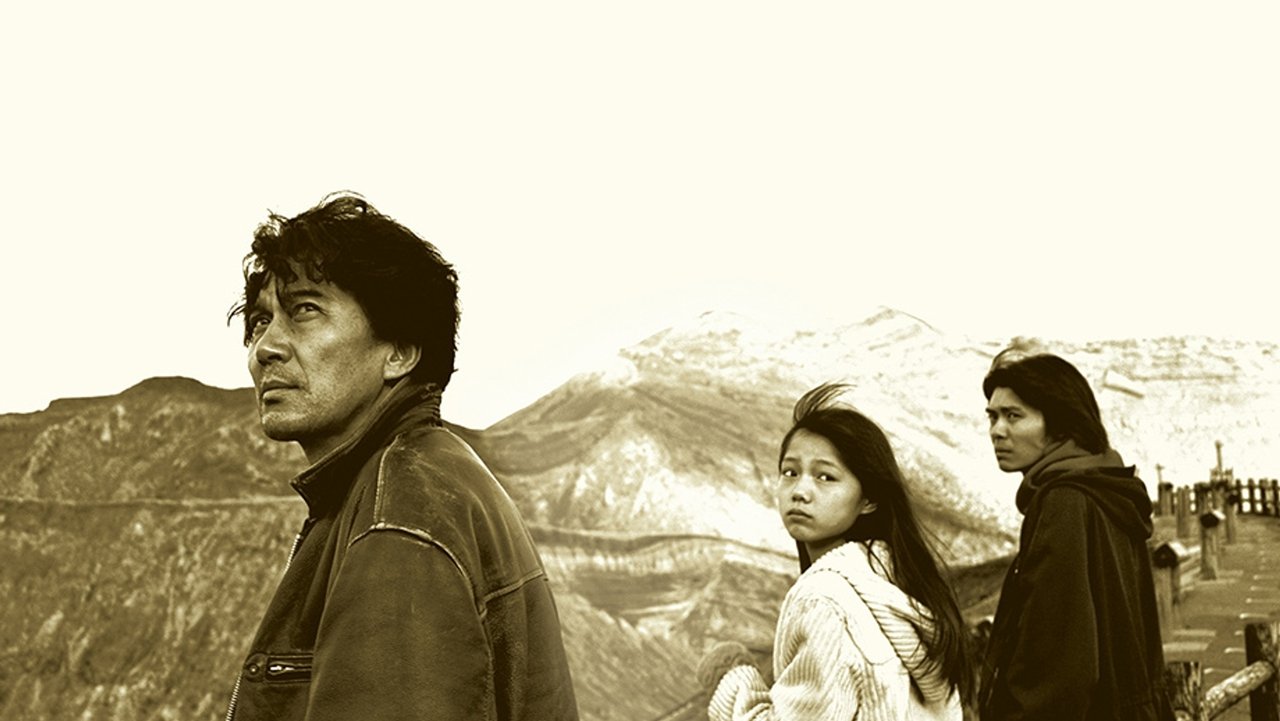

What unfolds is less a plot in the conventional sense and more an extended meditation on trauma, grief, and the tentative search for connection. When Sawai eventually returns, drawn back to the children by an unspoken bond of shared horror, he buys an old bus. Joined by their college-student cousin Akihiko (Yohichiroh Saitoh), this unlikely quartet embarks on a slow, meandering road trip across the desolate landscapes of Kyushu. It’s a journey with no clear destination, mirroring the characters' own uncertain paths toward healing.

The Power of Stillness

Aoyama's direction is deliberate, almost painterly. He favours long takes, static compositions, and allows silence to carry immense weight. The sepia monochrome isn't just an aesthetic choice; it bleeds the world of vibrancy, reflecting the internal landscape of the survivors. It forces you to focus on faces, on subtle shifts in body language, on the spaces between words. This isn't a film that rushes; it demands patience, immersing the viewer in the characters' numbed reality. It's a challenging watch, no doubt – I remember pausing the tape more than once, not from boredom, but simply to absorb the profound quietude.

The performances are nothing short of extraordinary, built on nuance rather than overt emoting. Koji Yakusho, already a familiar face to Western audiences from films like Shall We Dance? (1996) and the unsettling Cure (1997), delivers a masterclass in restraint. His Sawai is a man hollowed out by guilt and grief, his pain etched into the lines on his face, conveyed in weary glances and hesitant gestures. The young Miyazaki siblings are equally remarkable. Their shared trauma manifests as a profound withdrawal, a silent pact against a world that inflicted unspeakable harm. Watching Kozue slowly, tentatively begin to re-engage with the world is one of the film’s most potent, hard-won moments of grace.

A Journey Measured in Moments

While the film's length (a staggering 217 minutes) was and remains a talking point, it feels strangely necessary. Aoyama uses the time to let the journey breathe, to allow moments of quiet connection – a shared meal, a glance across the bus aisle, the simple act of moving forward – to accrue meaning. There's little traditional exposition; we piece together the emotional fragments alongside the characters. It’s a testament to Aoyama’s confidence that he trusts the audience to stay with these fractured souls, to understand that healing, if it comes at all, is rarely swift or linear.

Interestingly, the film premiered at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival, where it garnered significant acclaim, winning the FIPRESCI Prize and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury. This critical embrace perhaps highlights how Eureka, despite its demanding nature, struck a chord with those willing to engage with its profound exploration of human resilience in the face of overwhelming tragedy. It felt like a deliberate counter-programming to the often faster, louder pace of turn-of-the-millennium cinema.

Why It Lingers

Eureka isn't the kind of film you casually throw on. It requires commitment, attention, and a willingness to be enveloped by its somber beauty. It asks profound questions: How do we go on after the unimaginable? Can shared trauma forge new kinds of family? Where does the road lead when the old maps have been destroyed? The answers it offers are tentative, fragile, but ultimately imbued with a quiet sense of hope. It’s a film that seeps into your consciousness, its stark images and hushed tones lingering long after the final frame fades – much like an old photograph that holds more weight than its simple surface suggests.

Rating: 8.5/10

Justification: Eureka is a demanding masterpiece of slow cinema. Its challenging length and deliberate pacing might deter some, but for those willing to immerse themselves, it offers profound rewards. The performances are stunningly authentic, Aoyama's direction is masterful in its restraint, and the film's exploration of trauma and healing is deeply moving and insightful. The sepia cinematography is unforgettable. It loses a point and a half only for its sheer length and pace, which undeniably make it less accessible than many films, but its artistic achievement is undeniable.

Final Thought: A haunting, patient, and ultimately rewarding journey into the quiet landscape of survival, Eureka reminds us that sometimes the most significant journeys are the internal ones, undertaken one slow mile at a time.