Okay, fellow tapeheads, let’s dim the lights and settle in for something a little… different today. Usually, on VHS Heaven, we're queuing up explosive action flicks or comedies that defined a generation. But sometimes, digging through those video store aisles unearthed unexpected finds – films that challenged expectations and lingered long after the tape finished rewinding. Woody Allen's Interiors (1978) is precisely that kind of discovery. Landing just a year after the seismic success of Annie Hall, it represented such a stark, deliberate pivot into Bergmanesque chamber drama that finding it felt like uncovering a hidden, perhaps darker, side of a familiar filmmaker.

### A World Washed in Beige

Forget the bustling streets of Manhattan and the witty neuroticisms. Interiors invites us into a space defined by meticulous control and suffocating elegance. The film opens not with a joke, but with Arthur (E.G. Marshall), the patriarch of a well-off family, announcing his desire for a trial separation from his wife, Eve (Geraldine Page). This cracks the carefully constructed facade of their lives, exposing the emotional fault lines beneath. Eve, an interior designer obsessed with aesthetic perfection – favouring shades of beige, grey, and bone white – has imposed this same sterile control onto her family, leaving her three adult daughters struggling in its shadow. The film’s visual language, masterfully crafted by legendary cinematographer Gordon Willis (who shot The Godfather and Allen's own Annie Hall), mirrors this emotional landscape. Shot primarily in Long Island homes and NYC apartments, the camera often remains static, observing characters framed in doorways or against immaculately arranged, yet chillingly impersonal, backgrounds. The near-total absence of a musical score amplifies the uncomfortable silences and the weight of unspoken resentments. It’s a bold choice, forcing us to confront the raw emotions without melodic guidance.

### Echoes of Bergman, Whispers of Despair

There’s no skirting around it: the influence of Ingmar Bergman, particularly films like Cries and Whispers, looms large over Interiors. Allen has openly spoken of his admiration for the Swedish master, and this film is his most direct homage. Some critics at the time lauded the ambition, praising Allen for stretching his artistic muscles beyond comedy; others dismissed it as derivative, a skillful but ultimately hollow imitation. Watching it now, decades later, the comparison feels less like a critical point and more like a key to understanding the film's intent. Allen uses the Bergman framework – the intense focus on psychological turmoil within a confined family unit, the existential dread, the stark visual style – to explore themes that resonate within his own body of work: artistic frustration (seen in daughter Renata, played by Diane Keaton), intellectual paralysis, and the terrifying fragility of relationships built on pretense. It was a risky move, especially following the universally beloved Annie Hall, and while it only grossed about $10.4 million on a $10 million budget (a far cry from his comedic hits), its five Academy Award nominations (including Best Director and Original Screenplay for Allen) proved that the industry recognized the artistic merit of this somber departure.

### Performances Etched in Ice and Fire

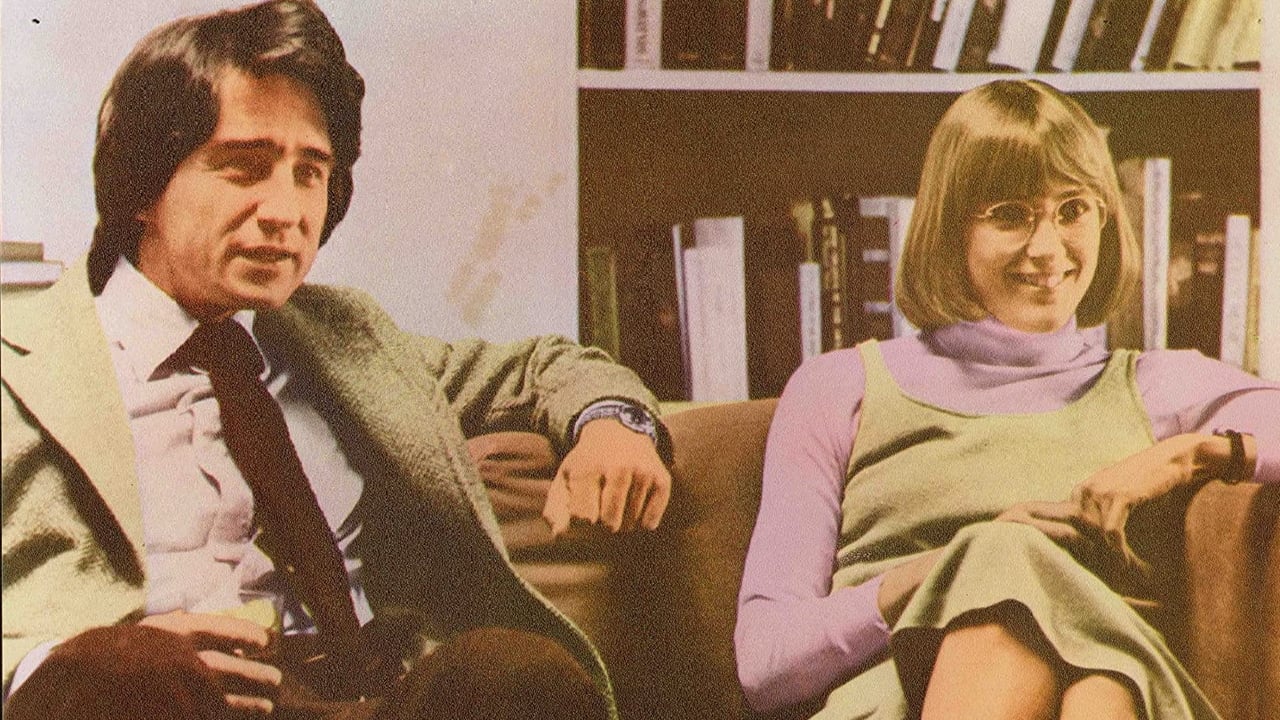

Where Interiors truly finds its power is in the phenomenal performances. Geraldine Page is devastating as Eve, a woman whose obsession with external perfection masks a terrifying internal void. Her control is a shield, her pronouncements on taste a desperate attempt to impose order on unbearable emotional chaos. Page embodies this fragility and repressed hysteria with heartbreaking precision, earning her a well-deserved Oscar nomination.

Contrasting Eve’s icy fragility is the arrival of Pearl, Arthur’s warm, vibrant, and decidedly un-beige new partner, played with magnificent, earthy gusto by Maureen Stapleton (also Oscar-nominated). Pearl is all vibrant reds and genuine laughter – life itself intruding upon Eve’s carefully curated mausoleum. The tension between these two women, and the different ways the daughters react to Pearl, forms the film’s emotional crucible. Diane Keaton as Renata, the acclaimed poet unable to feel her own success, and Mary Beth Hurt as Joey, the youngest daughter desperately searching for a meaningful path outside her mother's shadow, deliver performances of raw, understated pain. Their struggles feel agonizingly real, capturing the complex dynamics of sibling rivalry and the suffocating weight of parental expectation. Richard Jordan as Renata’s frustrated novelist husband adds another layer of simmering discontent. It’s a showcase of actors navigating incredibly difficult emotional terrain with nuance and power. Allen’s decision to stay entirely behind the camera allows these performances to dominate, unmediated by his familiar on-screen persona.

### A Chilling Portrait, A Difficult Watch

Interiors is undeniably challenging. It’s a film that requires patience and a willingness to sit with discomfort. There are no easy answers, no cathartic releases in the traditional sense. It’s a meticulous study of dysfunction, grief, and the destructive nature of perfectionism sought at the expense of human connection. For those expecting Allen’s wit, its somber tone and deliberate pacing might feel alienating. Yet, its artistic control, the haunting beauty of Gordon Willis’s cinematography, and the sheer force of the performances make it a compelling, if demanding, experience. It’s a film that doesn’t seek to entertain in the conventional way, but rather to dissect, observe, and leave the viewer contemplating the cold corners of the human heart. Finding this on VHS, nestled perhaps mistakenly between comedies, must have been a startling experience for many renters back in the day – a quiet shock to the system.

Rating: 7.5/10

Justification: Interiors earns this score for its artistic bravery, stunning cinematography, and powerhouse performances, particularly from Page and Stapleton. Allen's direction is precise and assured, creating an unforgettable, albeit chilling, atmosphere. It loses points perhaps for its heavy-handed Bergman influence, which sometimes borders on imitation, and its demanding, bleak nature which limits its rewatchability for a general audience compared to his more accessible works. It’s a film more admired than loved, but its craft is undeniable.

Final Thought: While it might not be the Woody Allen film you reach for on a Friday night, Interiors remains a significant, starkly beautiful entry in his filmography – a chilling reminder that sometimes the most meticulously designed spaces contain the most profound emptiness.