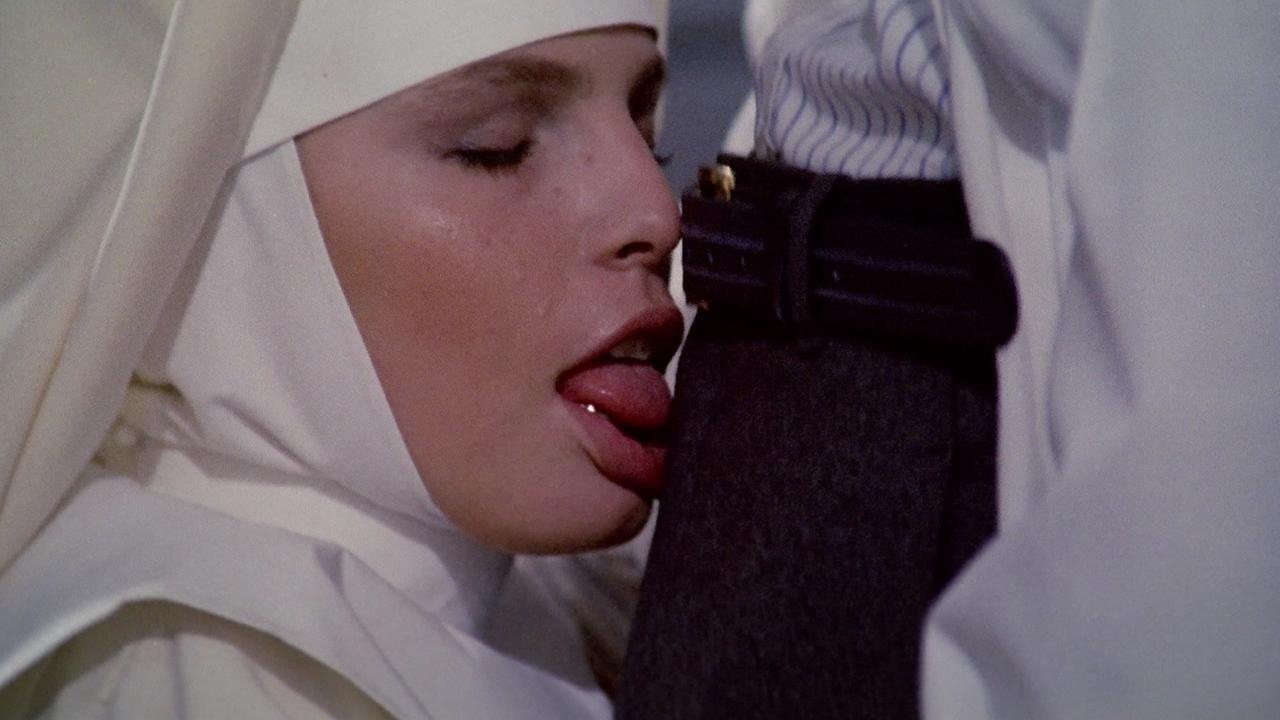

The sterile white of the habit should signify purity, devotion, solace. But watch closely as the fabric strains against Anita Ekberg’s frame in Giulio Berruti’s Killer Nun (original title: Suor Omicidi), and you see something else entirely. It becomes a shroud, clinging to a soul unraveling thread by painful thread. This isn't the angelic serenity promised by religious iconography; it's the cold sweat of withdrawal, the flicker of paranoia in the eyes, the oppressive weight of secrets festering within the walls of a geriatric hospital managed by nuns. Forget jump scares; this 1979 slice of Italian unease burrows under your skin with the slow, grinding dread of psychological collapse.

A Crisis of Faith and Flesh

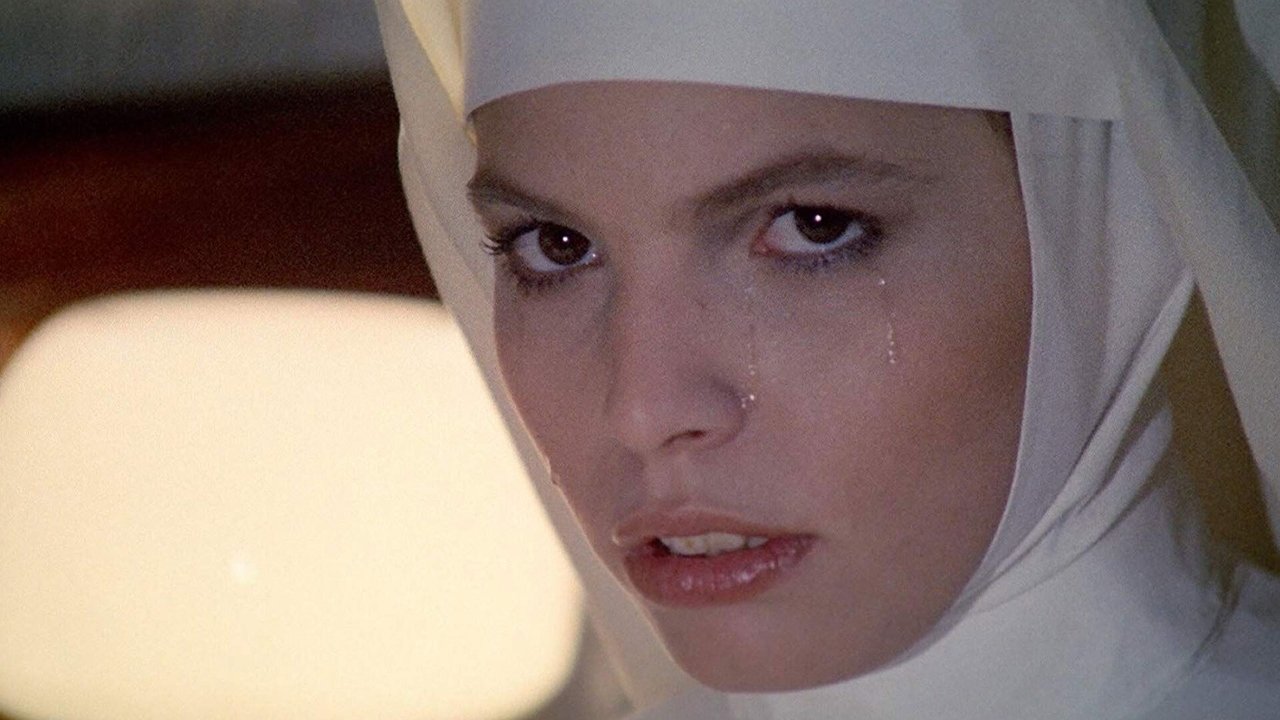

The film plunges us into the deteriorating world of Sister Gertrude (Anita Ekberg). Following surgery for a brain tumor, she develops a crippling morphine addiction, leading to violent outbursts, disturbing hallucinations, and erratic, often cruel, behavior towards the elderly patients under her care. The hospital, meant to be a place of healing, transforms into a claustrophobic stage for Gertrude’s descent. Berruti, who also co-wrote the screenplay with Alessandro Parenzo, doesn't shy away from the grim realities of addiction or the unsettling juxtaposition of sacred vows and profane actions. Is Gertrude possessed, genuinely mentally ill, or is something even more sinister afoot within the convent's hierarchy? The ambiguity is part of the film's chilling power.

It's impossible to discuss Killer Nun without focusing on Anita Ekberg. Decades removed from her iconic splash in Fellini's La Dolce Vita (1960), Ekberg delivers a performance of raw, uncomfortable commitment. She fully embodies Gertrude's torment, swinging wildly between moments of lucidity, narcotic haze, sexual frustration, and terrifying aggression. It's a brave, deglamorized turn that anchors the film's often lurid proceedings. You can almost feel the damp chill of the hospital corridors clinging to her performance. Adding a touch of class and gravitas is the legendary Alida Valli (instantly recognizable from The Third Man (1949) and Argento's Suspiria (1977)) as the stern Mother Superior, observing Gertrude's breakdown with a mixture of concern and suspicion. Her presence lends a certain eerie authority to the grim goings-on.

The Shadow of Truth

What lends Killer Nun an extra layer of disquiet is its claim to be based on a true story from Belgium. While the exact details remain murky – often the case with exploitation marketing – the mere suggestion that such profound corruption and violence could occur within consecrated walls adds a disturbing resonance. It taps into anxieties about hidden institutional abuse and the fallibility of those expected to be paragons of virtue. This wasn't just shock value; it was rooting the horror in a possibility that felt chillingly real, especially watching it unfold on a grainy VHS tape late at night, the flickering images amplifying the sense of unease. Remember how those "Based on True Events" tags felt back then? They carried a different kind of weight, didn't they?

The film firmly belongs to the notorious "nunsploitation" subgenre that thrived in Italian cinema during the 70s. However, compared to some of its more overtly trashy brethren, Killer Nun carries a heavier, more somber atmosphere. While it certainly doesn't skimp on sleaze or moments of shocking violence (including some unsettling interactions with the elderly patients and Gertrude's increasingly bold transgressions), Berruti seems genuinely interested in the psychological horror of Gertrude's condition. The score often emphasizes discordant strings and unsettling ambiance over bombastic cues, contributing to the overall feeling of sickness and decay. The production design captures the sterile, impersonal feel of the institution, making it feel less like a sanctuary and more like a prison.

Legacy of Unease

Killer Nun isn't an easy watch, nor is it a traditionally "scary" horror film. Its power lies in its bleakness, its unflinching portrayal of addiction and mental breakdown within a transgressive context, and Ekberg's startlingly raw performance. It’s the kind of film that could genuinely upset viewers back in the day, pushing boundaries with its blend of religious iconography, psychological distress, and moments of exploitation cinema cruelty. Does it fully succeed? Perhaps not entirely. The pacing can lag, and some plot elements feel underdeveloped or purely sensationalistic. Yet, its central performance and suffocating atmosphere leave a lasting, uncomfortable impression.

This wasn't a tape you'd casually pop in for light entertainment. It felt... forbidden. Finding it tucked away in the "Horror" or perhaps even a vaguely labelled "Euro Cult" section of the video store felt like unearthing something illicit. The stark cover art, often featuring Ekberg in her habit looking decidedly unholy, promised something transgressive, and the film largely delivered on that grim promise.

VHS Heaven Rating: 6/10

Why this score? Killer Nun earns points for Anita Ekberg’s fearless central performance, its genuinely unsettling atmosphere, and its status as a standout (if grim) example of nunsploitation leaning into psychological horror. It successfully creates a pervasive sense of dread. However, it loses points for uneven pacing, occasionally veering into gratuitous sleaze that detracts from the psychological depth, and a narrative that sometimes feels muddled. It’s a flawed but fascinating and undeniably disturbing piece of 70s Italian cult cinema.

Final Thought: Decades later, Killer Nun remains a potent and uncomfortable watch, a relic from an era when exploitation cinema dared to mix the sacred and the profoundly profane, leaving you pondering the darkness that can hide beneath even the most pious facade. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most terrifying monsters are the ones wrestling within ourselves.