It’s difficult to discuss The China Syndrome without immediately addressing the elephant in the room, or rather, the near-meltdown just outside Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Released on March 16, 1979, this meticulously crafted thriller about the dangers of nuclear power and corporate malfeasance gained an almost terrifying prescience just twelve days later when the Three Mile Island nuclear accident occurred. Watching it again now, decades removed, that real-world echo still hangs heavy in the air, lending the film an unsettling weight that few purely fictional tales can ever achieve. This wasn't just a movie anymore; it felt like a warning flare fired just moments before the blaze.

### The Hum You Can't Ignore

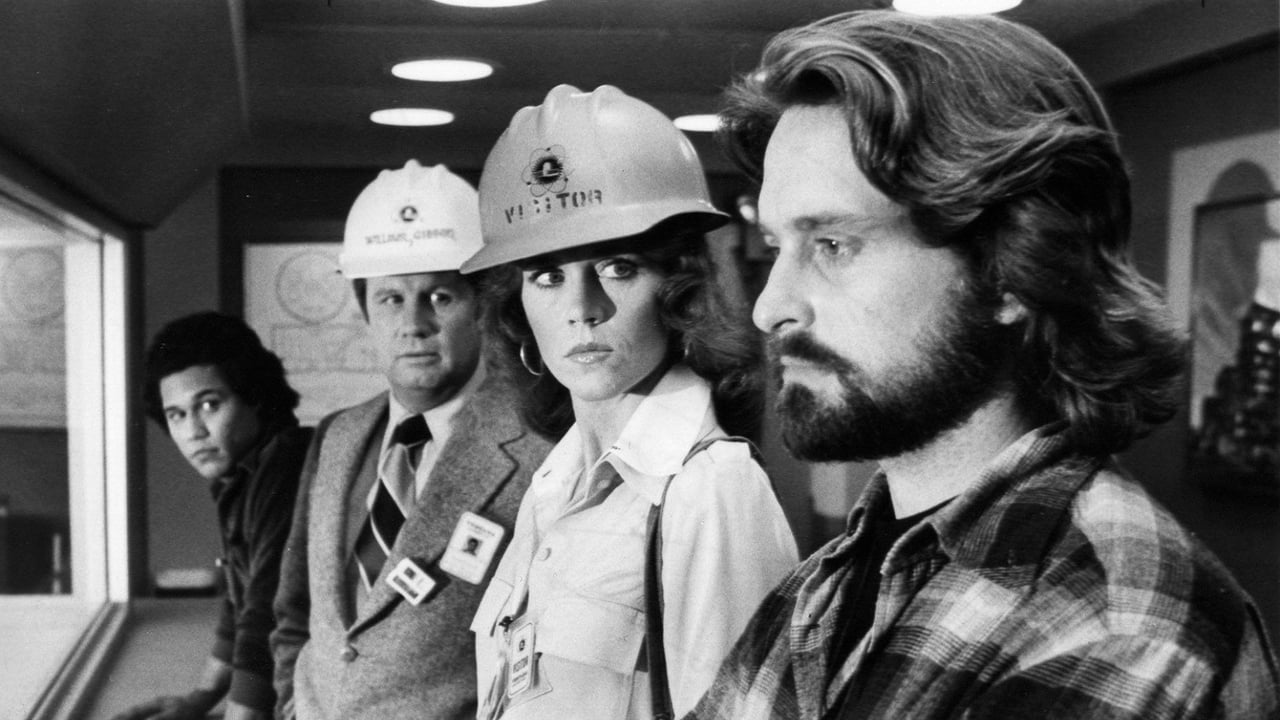

At its heart, The China Syndrome operates as a classic procedural thriller. Jane Fonda, embodying the ambitious but initially superficial television reporter Kimberly Wells, stumbles upon a potential catastrophe during a routine puff piece at the fictional Ventana nuclear power plant. Accompanied by her fiercely independent cameraman Richard Adams (a fiery, long-haired Michael Douglas, who also served as producer), they witness a sudden, violent "scram" – an emergency shutdown – hinting at something far more serious lurking beneath the facility's polished corporate veneer. The tension in that control room, palpable even through the flickering grain of a well-worn VHS tape, is immediate and visceral.

### The Weight on Jack Lemmon's Shoulders

While Fonda and Douglas drive the investigative plot forward, grappling with media ethics and corporate stonewalling, the film's soul resides with Jack Lemmon's masterful performance as Jack Godell, the plant's conscientious shift supervisor. Lemmon, often celebrated for his comedic genius (think Some Like It Hot or The Odd Couple), delivers arguably one of his finest dramatic turns here. He portrays Godell not as a crusading hero from the outset, but as a decent, dedicated company man whose faith in the system—and his own oversight—begins to terrifyingly erode. The subtle flickers of doubt that cross Lemmon’s face as he replays the incident in his mind, the growing knot of anxiety in his gut as he discovers falsified safety reports – it’s a study in mounting dread. His journey from unease to outright panic feels utterly authentic, the harrowing portrayal of a man realizing the horrifying potential consequences of cutting corners. You feel the immense pressure crushing him, the isolation of knowing a truth that others are desperate to bury. It's a performance built on nuance, not histrionics, making his eventual desperate actions all the more impactful.

### More Than Just a Thriller

Director James Bridges (who also co-wrote the sharp screenplay, drawing inspiration from real concerns voiced by engineers like Mike Gray) masterfully builds suspense not through flashy action sequences, but through claustrophobic confinement, technical jargon that sounds terrifyingly real (thanks to meticulous research and consultant input), and the slow, agonizing realization of danger. The clatter of Geiger counters, the imposing banks of lights and dials in the meticulously recreated control room (a set reportedly costing half a million 1979 dollars!), the hushed, urgent conversations in corridors – it all contributes to an atmosphere thick with paranoia and impending doom. Bridges understood that the true horror lay not in explosions, but in the potential, the unseen threat humming just beneath the surface, and the human fallibility that could unleash it.

### Retro Fun Facts: Beyond the Meltdown Timing

The film’s connection to Three Mile Island is its most famous piece of trivia, but there’s more beneath the surface. Michael Douglas, inspired by seeing Jane Fonda in Klute, specifically sought her out for the reporter role, developing the project as both star and producer. Fonda’s own well-documented anti-nuclear activism lent an extra layer of conviction to her portrayal and certainly fueled public interest. Studios were initially hesitant, wary of the controversial subject matter, until Columbia Pictures bravely took the plunge with a budget of around $5.9 million. Jack Lemmon himself reportedly needed convincing to take on such a serious role, but extensive research, including visits to actual power plants, solidified his commitment. The term "China Syndrome" itself, referring to a hypothetical core meltdown burning through its containment and theoretically down into the earth ("all the way to China"), was explained within the film, chillingly educating audiences about worst-case scenarios. Despite the weighty topic, the film was a critical and commercial success even before TMI, earning $51.7 million domestically and securing four Oscar nominations, including Best Actor for Lemmon and Best Actress for Fonda.

### Does It Still Radiate Tension?

Absolutely. While the technology depicted might look dated to younger eyes – the bulky TV cameras, the lack of instant global communication – the core themes remain startlingly relevant. Corporate accountability, the role of the media in uncovering truth, the potentially catastrophic consequences of prioritizing profit over safety... doesn't that sound familiar? The film doesn’t offer easy answers, presenting the complexities and ethical grey areas faced by individuals caught within powerful systems. What lingers most after the credits roll is the unsettling feeling that the potential for such crises, driven by human error and concealment, hasn't vanished with the VHS era. My own well-worn tape of this always felt less like entertainment and more like required viewing, a sentiment amplified by the eerie timing of its original release.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional craftsmanship, powerhouse performances (especially Lemmon's career-highlight turn), taut direction, and its chilling, almost accidental prescience. It's a top-tier thriller that transcends its era, losing none of its power to grip and provoke thought. The slight deduction acknowledges that the pacing, while deliberate and effective for tension-building, might feel slow to viewers accustomed to modern hyper-editing.

The China Syndrome remains a potent reminder of how quickly things can go wrong, and the courage it takes for one voice, however strained, to cry out against the hum of complacency. A true standout from the late 70s that still feels unnervingly current.