Here we are again, pulling another tape from the shelf, the static hiss of the VCR a familiar prelude. Tonight, it's 1987's A Prayer for the Dying, a film that arrived with considerable star power but carries the distinct air of something bruised, something compromised. It’s a film that asks a devastating question almost immediately: what happens when the sanctity of confession becomes a cage, trapping a good man with knowledge of pure evil?

A Killer's Conscience, A Priest's Crisis

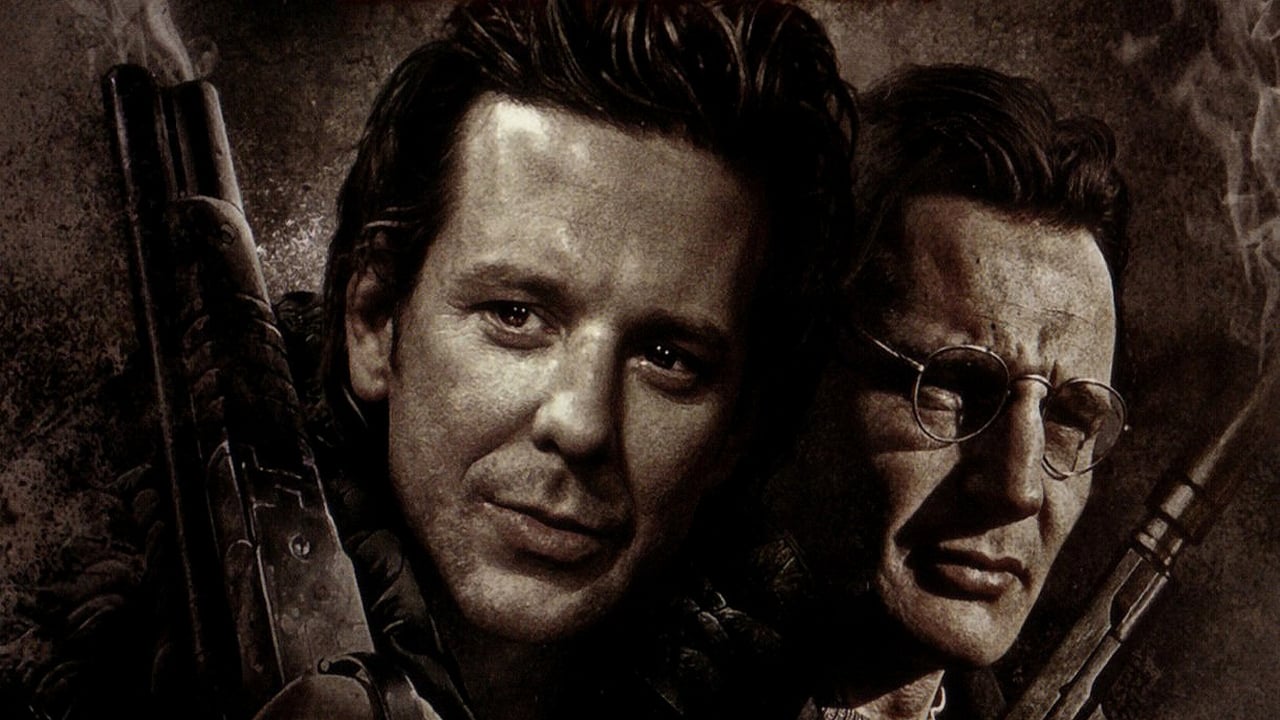

The premise hooks you with grim efficiency. Mickey Rourke, embodying that captivating blend of danger and vulnerability he owned in the 80s, plays Martin Fallon, an IRA operative whose soul cracks after a bomb intended for a military convoy tragically takes out a school bus instead. Haunted and desperate to leave the violent life behind, he flees to London. But freedom requires one last, ugly job for a chillingly pragmatic gangster, Jack Meehan, played with reptilian menace by the great Alan Bates. The act – a cold-blooded murder – is inadvertently witnessed by Father Michael Da Costa (Bob Hoskins), a Catholic priest tending his church grounds. Seeking absolution, or perhaps just needing to unburden his tormented spirit, Fallon confesses the murder to Da Costa, knowing the seal of the confessional protects him. It's a brilliant setup, instantly pitting Fallon's desperate gamble for peace against Da Costa's agonizing moral bind. Can a priest uphold his sacred vow when it shields a killer and obstructs justice?

Rourke and Hoskins: A Study in Contrasts

The film truly hinges on the dynamic between its two leads, and it's here that A Prayer for the Dying finds its most compelling moments. Rourke, fresh off intense roles in Angel Heart and 9½ Weeks, brings a brooding, almost spectral quality to Fallon. He’s a man hollowed out by violence, his desire for redemption palpable beneath layers of weary cynicism. There's a quiet intensity to his performance, a sense of coiled energy that feels authentic, even if whispers of his legendary on-set intensity sometimes feel present in the performance itself.

Opposite him, Bob Hoskins, known then for gritty turns like The Long Good Friday and his Oscar-nominated role in Mona Lisa, is the film's grounded, anguished heart. As Father Da Costa, he radiates decency under immense pressure. You feel the weight of his dilemma in every weary line on his face, the struggle between his faith's demands and his human desire for justice. The scenes where these two men confront each other, particularly within the charged space of the church and confessional, are electric. They represent two sides of a coin – one seeking escape from sin, the other trapped by the obligation to contain it. Look closely too, and you'll spot a young Liam Neeson in a supporting role as another IRA member, a hint of the formidable presence he would later become.

Whispers of a Troubled Soul

However, watching the film now, especially knowing its history, you can feel the spectral presence of studio interference. Mickey Rourke famously disowned the final cut, feeling it softened Fallon’s character and diluted the film’s political edge. He, along with director Mike Hodges (who gave us the stone-cold classic Get Carter), reportedly clashed with the Samuel Goldwyn Company over the edit and, crucially, the score. Rourke had apparently favoured a more atmospheric score by Mark Knopfler of Dire Straits, but the studio opted for a more conventional thriller score by Bill Conti. You can sense this tension; moments of quiet, character-driven reflection sometimes feel jarringly interrupted by thriller tropes that don't quite mesh with the prevailing mood. It feels like a film wrestling with itself – wanting to be a somber meditation on guilt and faith, but occasionally forced into the mold of a standard 80s action flick. Was the original vision a darker, more complex film lost to executive meddling? One can only wonder. The novel by Jack Higgins, on which it's based, certainly suggests a grittier potential.

London Through a Bleak Lens

Despite these issues, Mike Hodges' direction often captures a palpable sense of place. His London isn't Swinging London; it's a grey, rain-slicked landscape that mirrors Fallon's internal state. The decaying industrial areas and the imposing architecture of the church become characters in themselves, environments that feel both isolating and potentially dangerous. Hodges has a knack for atmosphere, and even if the narrative coherence sometimes falters, the mood often remains potent. You get the feeling of a filmmaker trying to imbue the proceedings with a weight that the final edit occasionally undermines.

Retro Fun Facts

- Rourke's Disavowal: His public criticism of the film was quite vocal at the time, a rare move for a star of his stature, highlighting his artistic dissatisfaction. He felt the studio turned a serious drama into something more generic.

- Location Shooting: The film utilized gritty London locations, adding to its authenticity. The prominent church used for filming was St. Patrick's Church in Wapping, East London.

- Hodges' Frustration: Like Rourke, director Mike Hodges was reportedly unhappy with the final version released by the studio, feeling his intended tone and focus were compromised.

- Critical Reception: Reviews at the time were mixed, often praising the performances (especially Hoskins and Bates) but noting the uneven tone and perceived studio compromises, echoing the sentiments of the star and director.

Does it Hold Up?

Revisiting A Prayer for the Dying on VHS, or perhaps via a streaming service dredging the depths of 80s cinema, is a fascinating experience. It’s undeniably flawed, bearing the scars of its troubled production. The tonal shifts can be jarring, and the plot mechanics sometimes feel forced. Yet, the central performances remain powerful, particularly the interplay between Rourke and Hoskins. The core moral dilemma is timeless and thought-provoking. It doesn't quite reach the heights of the best thrillers or character studies of the era, but it possesses a haunting quality that lingers. It feels like a film reaching for something profound, even if it doesn't fully grasp it.

Rating: 6/10

Justification: The strong central performances from Rourke, Hoskins, and Bates, coupled with the potent moral premise and Hodges' atmospheric direction, elevate the material significantly. However, the film is undeniably hampered by its apparent studio interference, leading to an uneven tone and a sense that its potential wasn't fully realized. It’s a compelling watch, but ultimately feels compromised.

Final Thought: A Prayer for the Dying remains a compelling curio from the VHS era – a film haunted not just by its protagonist's sins, but by the ghost of what it might have been. It leaves you pondering the weight of secrets and the often-impossible choices faith demands.