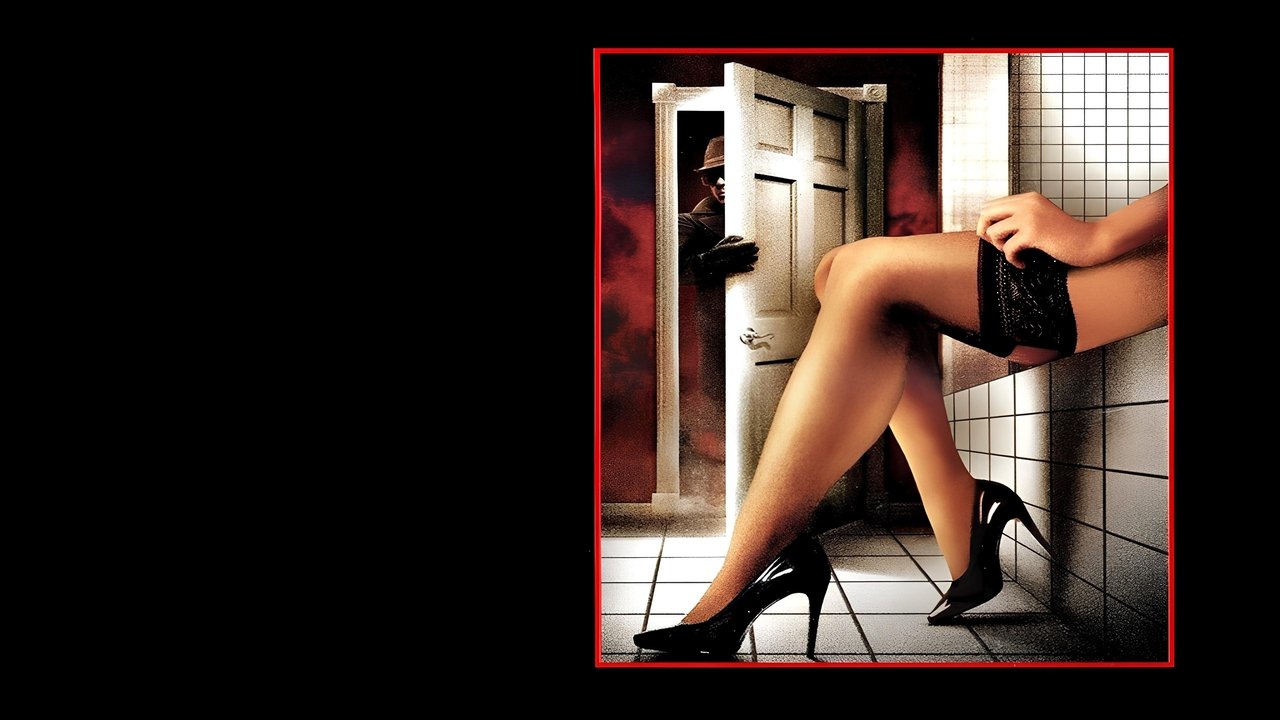

The opening sequence lingers, doesn't it? That slow pan across the shower, the steam clinging to skin, the deliberate sensuality underscored by Pino Donaggio’s lush, almost heartbreakingly romantic score. It feels intimate, almost uncomfortably so. And then, the cut. Brian De Palma’s Dressed to Kill (1980) throws you into its world of repressed desires and sudden, brutal violence with a confidence that’s both dazzling and deeply unsettling. This wasn't just another slasher flick cluttering the shelves down at the video store; it felt… expensive. Polished. And dangerous.

A Symphony of Suspense and Style

Forget the gritty realism that was creeping into horror; De Palma, ever the provocateur and cinephile, crafts something closer to a waking nightmare draped in haute couture. The film looks incredible. The cinematography glides, observes, sometimes lingers too long, making the audience complicit voyeurs. De Palma’s signature moves are all here: the audacious split-screen sequences ratcheting up tension by showing simultaneous actions, the almost fetishistic slow-motion captures of violence or revelation, the long, dialogue-free stretches where suspense builds purely through image and sound. Remember that incredible sequence in the Philadelphia Museum of Art? It’s practically a silent film, a masterclass in visual storytelling as Kate Miller (Angie Dickinson) engages in a flirtatious game of cat and mouse. It’s elegant, playful, and utterly nerve-wracking because you know De Palma isn’t just playing games.

Shadows and Secrets

At its core, Dressed to Kill is a psychosexual thriller revolving around Kate, a sexually frustrated Manhattan housewife, her sessions with psychiatrist Dr. Robert Elliott (Michael Caine), and the aftermath of a fateful afternoon tryst. When Kate becomes the victim of a razor-wielding killer in a blonde wig, high-class call girl Liz Blake (Nancy Allen) witnesses the attack, inadvertently becoming both the next target and the key to unraveling the mystery, aided by Kate's tech-savvy son, Peter (Keith Gordon).

Angie Dickinson is remarkably vulnerable and complex as Kate, portraying her yearning and anxieties with a raw honesty that makes her subsequent fate all the more shocking. Nancy Allen (De Palma’s wife at the time, following their collaboration on Carrie four years earlier) brings a street-smart energy and unexpected warmth to Liz, the accidental detective navigating a deadly situation. And then there's Michael Caine. Suave, reassuring, perhaps slightly aloof as Dr. Elliott, he anchors the film's central enigma. It’s a controlled performance that keeps you guessing, layered with subtleties that pay off chillingly later.

Echoes of the Master

Let's address the shower scene in the room: the Hitchcock comparisons. Yes, the influence of Psycho (1960) hangs heavy over Dressed to Kill – from the shocking demise of the perceived protagonist early on, to the themes of psycho-sexual disturbance and cross-dressing. De Palma never shied away from his reverence for Hitchcock, but to dismiss this as mere imitation is to miss the point. De Palma takes Hitchcockian themes and visual language and pushes them further, amplifying the style, the eroticism, and the violence through his own distinct, operatic lens. It’s homage turned up to eleven, filtered through a late-70s/early-80s sensibility. Was it derivative? Maybe. Was it electrifying? Absolutely.

Behind the Silken Curtain

The film wasn't without its behind-the-scenes whispers and controversies, even beyond the Hitchcock debate. The graphic violence, particularly the infamous elevator murder sequence, pushed boundaries and inevitably led to battles with the MPAA, resulting in different cuts being released over the years. Fun fact: the production reportedly shelled out $75,000 just for the rights to show artworks in that museum sequence. There was also considerable buzz (and perhaps some deliberate smoke and mirrors) surrounding the use of a body double for Angie Dickinson during the opening shower scene – a detail that only added to the film's provocative reputation back in the day. Made for around $6.5 million, Dressed to Kill became a significant box office success, pulling in nearly $32 million domestically – proof that De Palma's slick, controversial brand of suspense struck a chord.

A Sharp Edge That Still Cuts

Watching Dressed to Kill today is a fascinating experience. The style remains undeniably potent. Donaggio’s score is still magnificent, arguably one of the best thriller scores of the era. The suspense sequences, particularly the museum and subway chases, are expertly crafted examples of pure cinematic tension. However, viewed through a modern lens, the film's depiction of gender identity and violence against women is undeniably problematic and has drawn significant criticism over the years. It reflects certain anxieties and exploitative tendencies of its time, and that aspect can be jarring. It’s a conversation worth having, acknowledging the film's flaws alongside its technical brilliance. Did that final jump scare still get you, even knowing it was coming? It’s pure De Palma showmanship.

Rating: 8/10

Dressed to Kill earns its high marks for its sheer audacity, visual mastery, and unforgettable suspense sequences. Brian De Palma delivers a supremely stylish, deeply unnerving thriller powered by strong performances and an iconic score. It's a film that grabs you by the throat with its elegance before delivering calculated shocks. While certain elements haven't aged gracefully and court valid controversy, its power as a slick, boundary-pushing example of the erotic thriller, and as a key work in De Palma's often divisive filmography, remains undeniable. It’s a high-gloss nightmare that, once seen, is hard to shake off – a perfect slice of sophisticated, adult-oriented dread from the shelves of VHS Heaven.