It's a strange thing, revisiting a film that carries the weight of not one, but two distinct legacies. On one hand, there's the monumental shadow of the 1927 original The Jazz Singer, the film that famously ushered in the era of sound cinema. On the other, there's the curious case of its 1980 remake, a vehicle seemingly tailor-made for music superstar Neil Diamond that landed with a critical thud but resonated deeply through its chart-topping soundtrack. Pulling that worn VHS tape off the shelf today sparks a complex mix of memories – the undeniable power of those songs blasting from the car radio, paired with a hazy recollection of a film that felt both deeply earnest and, let's be honest, a little bit baffling.

Echoes of an Older Song

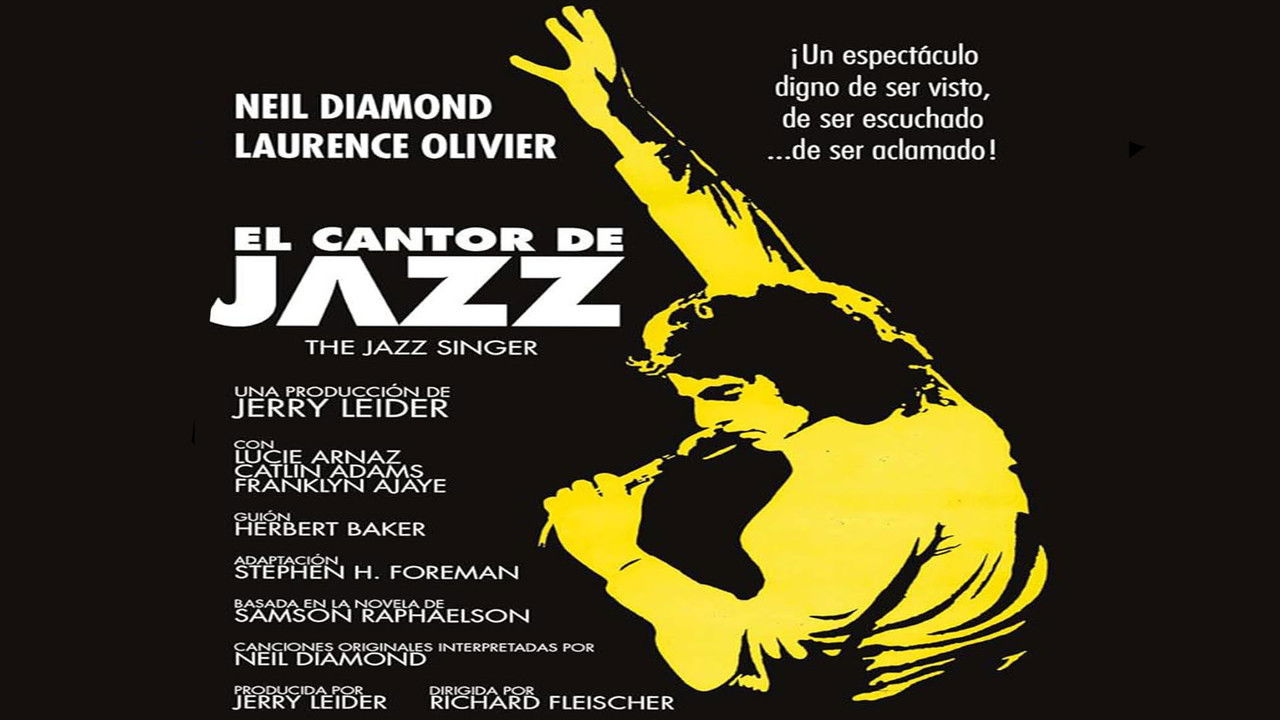

Directed by Richard Fleischer (a versatile journeyman known for everything from Disney's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea to the gritty sci-fi of Soylent Green), this updated Jazz Singer transplants the core conflict to the then-contemporary world of 1980. Jess Robin (Neil Diamond), the son of a rigidly traditional Jewish cantor, feels the irresistible pull of pop music stardom, a world away from the synagogue where his father, Cantor Rabinovitch (played by none other than Sir Laurence Olivier), expects him to follow in his footsteps. It’s the age-old story: tradition versus modernity, familial duty versus personal calling, faith versus fame. The framework is potent, carrying inherent dramatic weight. But how does this version, nearly sixty years removed from the Al Jolson original, navigate these themes?

Diamond in the Rough... or Just Rough?

Let's address the elephant in the room, or rather, the sequined-shirt-wearing superstar. Neil Diamond's performance as Jess Robin earned him the first-ever Razzie Award for Worst Actor, a perhaps unduly harsh welcome to the world of cinema for the singer-songwriter. Watching it now, "bad" feels too simplistic. Diamond possesses an undeniable charisma, a certain soulful intensity that works wonders when he's performing the film's standout musical numbers. You believe his passion when he’s singing. However, in the dramatic scenes, particularly opposite a theatrical titan like Olivier, his lack of acting experience is often apparent. There's an earnestness, yes, but also a stiffness, a sense of someone trying very hard rather than simply being. It’s reported Diamond had significant creative control, and one wonders if a different directorial approach – original director Sidney J. Furie (Lady Sings the Blues) was replaced by Fleischer early on – might have yielded a different result. Still, his musical magnetism is the film's undeniable engine.

An Acting Legend Stirs Debate

And then there's Laurence Olivier. Securing perhaps the greatest actor of the 20th century for the role of the devout, Yiddish-accented cantor was a casting coup, but his performance remains a point of contention. Olivier dives in with ferocious commitment, delivering a performance that is undeniably powerful, theatrical, and... well, big. For some, it borders on caricature, earning him his own Razzie for Worst Supporting Actor. Yet, beneath the sometimes-heavy accent and theatricality, there are moments of genuine pathos, the raw pain of a father seeing his world, his faith, and his son seemingly slip away. It’s a performance that refuses to be ignored, fascinating even in its potential missteps. What does it say when an actor of such legendary status delivers a portrayal that divides audiences so sharply? Doesn't it force us to consider the very nature of "screen presence" versus perhaps "stage presence"?

Soundtrack Supremacy and a Steady Hand

While the central performances drew fire, Lucie Arnaz (daughter of TV royalty Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz) provides a grounding presence as Molly Bell, Jess's manager and love interest. She brings a naturalism and warmth that serves as a welcome counterpoint to the high drama surrounding her. But the film's true MVP, the element that lodged The Jazz Singer firmly in the cultural consciousness of the early 80s, is its soundtrack. Diamond penned and performed instant classics like the soaring "America," the heart-wrenching ballad "Love on the Rocks," and the smooth "Hello Again." The album was a monumental success, going multi-platinum and far eclipsing the film's critical reception. It’s likely many reading this owned the cassette or LP long before, or perhaps instead of, ever renting the movie. This disconnect between cinematic critique and musical triumph is one of the film's most intriguing facets.

A Curious Footnote in Film History

Despite the critical drubbing, The Jazz Singer wasn't a financial disaster. Made for around $13 million, it pulled in over $27 million domestically – a respectable return in 1980. It even holds the strange distinction of being nominated for both an Oscar (for Isidore Mankofsky's cinematography) and multiple Razzies (winning two). Perhaps its earnest exploration of timeless themes, combined with the sheer star power of Diamond and the undeniable pull of the music, struck a chord with audiences, even if critics remained unmoved. It captures a specific moment – the cusp of the 80s, grappling with old traditions in a rapidly changing world, all set to a distinctly Diamond soundtrack. Seeing the New York locations, the fashion, the feel of the era – it certainly sparks that nostalgic recognition for those of us who remember that time.

The Verdict

Revisiting The Jazz Singer on VHS feels like uncovering a time capsule. It's flawed, certainly. The central performance is uneven, and Olivier's turn remains divisive. Yet, there's an undeniable sincerity to its ambition, a potent emotional core buried beneath the occasionally awkward execution. The music remains spectacular, arguably justifying the entire endeavor for Diamond's legions of fans. It’s a fascinating artifact – a remake of a landmark film, a superstar's bold (if perhaps ill-advised) leap into acting, a critical punching bag that nonetheless produced a beloved, enduring soundtrack. Does it fully work as a film? Perhaps not consistently. But is it watchable, memorable, and a unique piece of 80s pop culture history? Absolutely.

Rating: 5/10 - This rating reflects the film's significant flaws, particularly in the dramatic performances, but acknowledges the undeniable power and success of its soundtrack, the earnest attempt to tackle meaningful themes, and its status as a fascinating, if flawed, piece of 80s cinema history. It's a movie saved, in many ways, by its music.

That final image of Jess, caught between two worlds, trying to reconcile his heritage with his dreams... it still lingers, doesn't it? Perhaps that internal conflict, more than the execution, is what truly resonates decades later.