There are screen performances that feel like acting, and then there’s Robert Duvall in Tender Mercies. Watching this 1983 film again, decades after first finding its unassuming VHS box nestled amongst the louder offerings at the local rental store, feels less like revisiting a movie and more like observing a life quietly unfolding. It's a film that doesn't shout its intentions; it simply is, trusting the viewer to lean in and listen to the stillness. What lingers most, perhaps, is the profound sense of authenticity it achieves, a quiet power that feels almost radical compared to much of the decade's cinematic output.

Dust, Silence, and a Broken Song

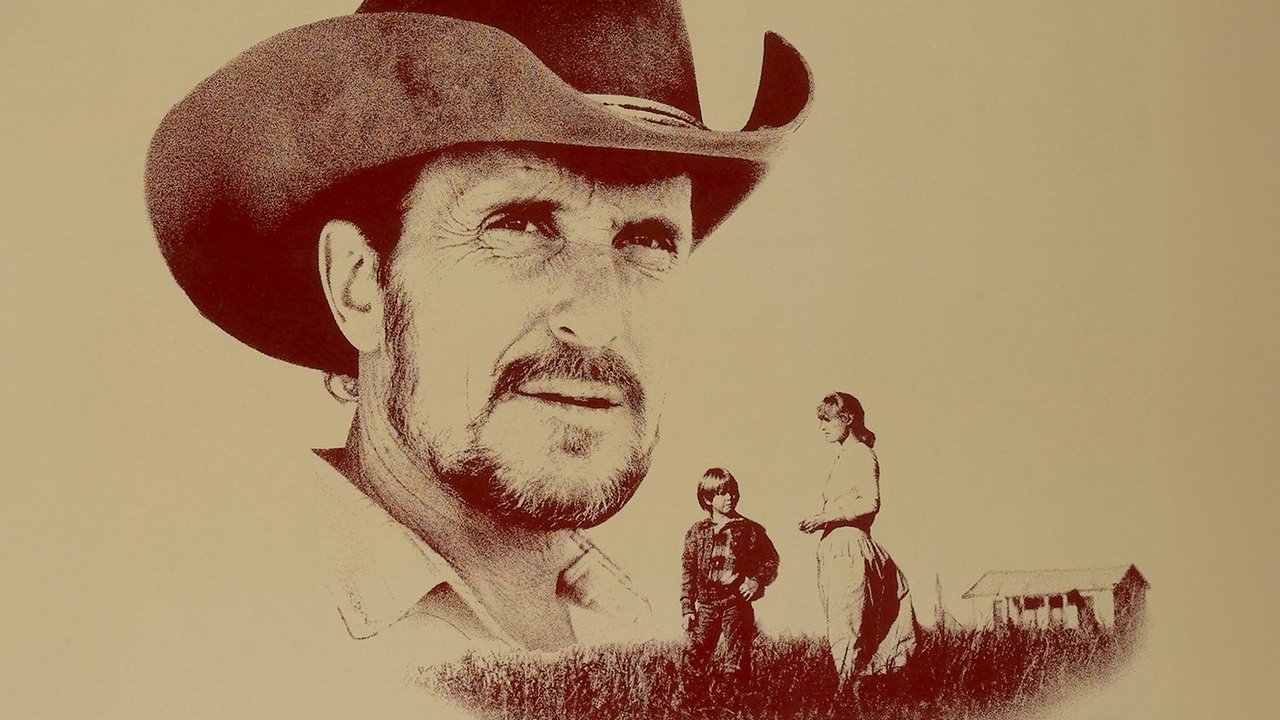

The premise, penned by the legendary playwright Horton Foote (who deservedly won an Oscar for his work here), is deceptively simple. Mac Sledge (Duvall), a once-famous country singer ravaged by alcoholism, wakes up broke and adrift in a desolate Texas motel and gas station run by the young widow Rosa Lee (Tess Harper) and her son, Sonny (Allan Hubbard). He takes a job, finds a measure of peace, and cautiously begins to piece together a semblance of a life. There’s no sudden, dramatic conversion; redemption here is a slow, tentative process, marked by setbacks and whispered prayers. Director Bruce Beresford, an Australian filmmaker perhaps best known then for Breaker Morant (1980) and later for Driving Miss Daisy (1989), masterfully captures the stark beauty and quiet despair of the Texas landscape, making it as much a character as any person on screen. The wide, empty shots emphasize Mac's isolation but also the vast potential for a new beginning, however fragile.

The Weight of Unspoken Words

What truly sets Tender Mercies apart is its profound understanding of silence and subtext. Foote’s dialogue is sparse, realistic, reflecting how people often communicate more through what they don't say. Scenes unfold with a patient rhythm, allowing moments of quiet reflection or awkward hesitation to carry significant weight. Consider the tentative conversations between Mac and Rosa Lee, the gradual building of trust, the unspoken understanding that flickers between them. It demands attention, rewarding the viewer who is willing to observe the subtle shifts in expression, the slight gestures that reveal deep wells of emotion. This isn't a film driven by plot twists, but by the internal shifts of its characters. Doesn't this approach feel more true to how real change often happens – gradually, almost imperceptibly?

Duvall's Masterclass in Understatement

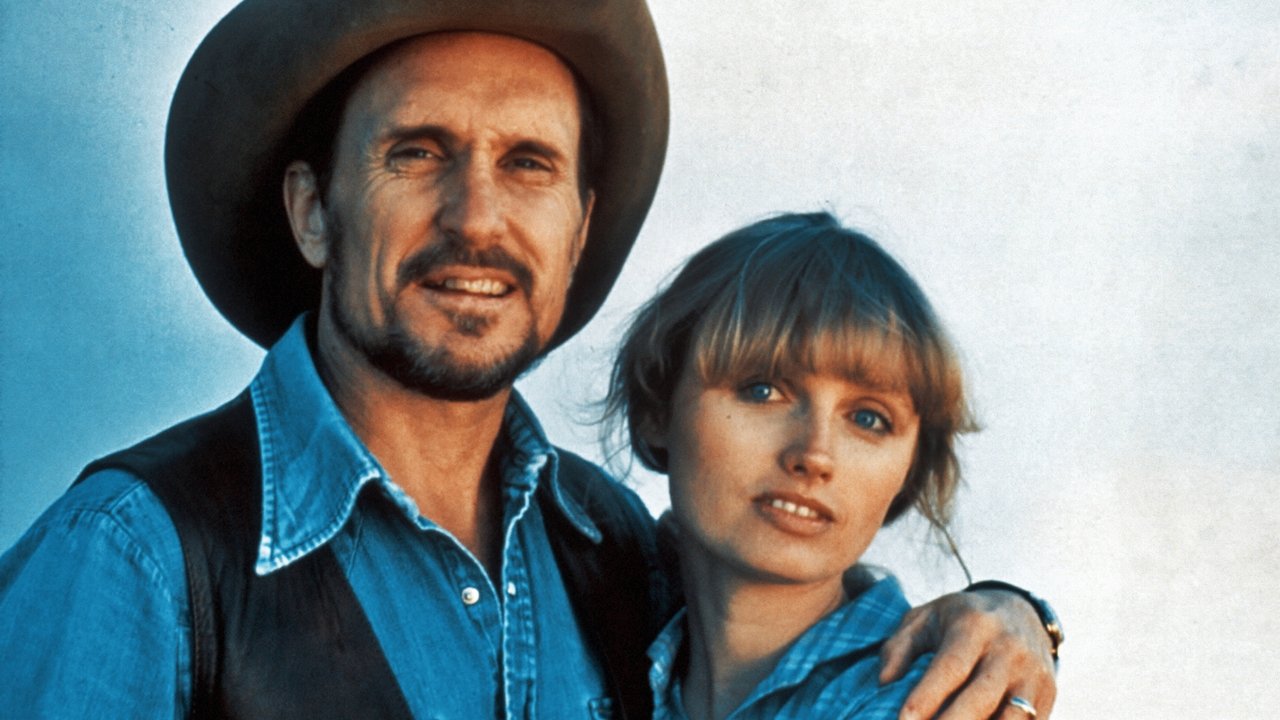

And at the heart of it all is Robert Duvall. His portrayal of Mac Sledge is less a performance and more an inhabitation. There's no vanity, no actorly flourish; just the raw, weathered truth of a man grappling with his demons and cautiously reaching for grace. Duvall famously immersed himself in the role, traveling through Texas, absorbing local accents, and even writing and performing two of the film's songs ("It Hurts to Face Reality" and "Fools Waltz") himself. You believe him as a man who has known fame and squandered it, who carries the weight of his past in every line on his face and every weary movement. It’s a study in restraint, proving that immense power can be conveyed through the quietest moments. His eventual Oscar win felt less like an industry award and more like simple recognition of an undeniable truth captured on film.

Finding Grace in Unexpected Places

The supporting cast is equally vital in creating the film's delicate ecosystem. Tess Harper, in her remarkable film debut (discovered after working in Texas theater), brings a quiet strength and inherent decency to Rosa Lee. She embodies the film's title – offering mercy not out of pity, but from a place of quiet understanding and faith. Her chemistry with Duvall is built on shared vulnerability and tentative hope, never feeling forced or sentimental. Young Allan Hubbard as Sonny provides Mac with a reason to strive for stability, their bond forming naturally through shared chores and quiet moments. And Betty Buckley, fresh off her Tony win for Cats on Broadway, offers a stark contrast as Mac’s ex-wife, Dixie, a successful country star still navigating the fallout of their tumultuous past. Her scenes crackle with unresolved history and pain, reminding us of the life Mac left behind.

Retro Fun Facts: An Underdog's Journey

The story behind Tender Mercies is almost as compelling as the film itself. Duvall actually discovered Foote's script himself and was instrumental in getting it made, bringing it to Beresford. Made for a modest $4.5 million (around $13.8 million today), the film initially struggled mightily to find distribution. EMI Films, the production company, had little faith in its commercial prospects. Universal Pictures eventually picked it up but offered minimal marketing support. It seemed destined to disappear. However, glowing critical reviews and persistent word-of-mouth built momentum, transforming it from a potential write-off into an awards contender. Filmed entirely on location in small Texas towns like Waxahachie, using real, functioning businesses like the motel and gas station, adds immeasurably to its grounded feel. Its eventual success, culminating in two major Academy Awards (Actor and Screenplay, plus nominations for Picture, Director, and Song "Over You"), felt like a victory for quiet, character-driven filmmaking in an era often dominated by spectacle.

A Quiet Echo

Tender Mercies isn't a film you watch for thrills or easy answers. It’s a meditation on regret, faith, the possibility of second chances, and the simple, profound mercies that can sustain us. It requires patience, but the emotional payoff is immense and deeply resonant. It’s a film that stays with you, its quiet observations echoing long after the screen goes dark. Finding it on VHS back then felt like uncovering a hidden treasure, a piece of quiet artistry amidst the noise.

Rating: 9/10

The near-perfect execution of its minimalist vision, anchored by one of the great screen performances, makes this an enduring classic. Its deliberate pacing might test some viewers, but its emotional honesty and quiet power are undeniable.