Sometimes a film doesn't just tell a story; it envelops you in a mood, a pervasive sense of searching that lingers long after the tape has clicked off. Michelangelo Antonioni's Identification of a Woman (1982) is precisely that kind of film. It washes over you like the dense fog that so frequently obscures its Roman and Venetian landscapes, leaving behind a chill of ambiguity and the echo of unanswered questions about connection, desire, and the very nature of seeing. Watching it again now, decades removed from its initial release, feels like unearthing a particularly fragile, complex artifact from the arthouse corner of the old video store – a challenging, sometimes frustrating, yet undeniably hypnotic experience.

A Director Adrift

The premise is deceptively simple: Niccolò (a fascinatingly cast Tomás Milián), a film director wrestling with creative and personal voids after his wife leaves him, embarks on a search. He's looking for a new face for his next film, but more profoundly, he seems to be searching for something – an anchor, an understanding, perhaps even an understanding of women themselves, who remain stubbornly outside his grasp. His journey leads him into intense, fragmented relationships with two enigmatic figures: the aristocratic, emotionally volatile Mavi (Daniela Silverio) and the earthy, seemingly more grounded Ida (Christine Boisson). Neither offers easy answers or stable ground.

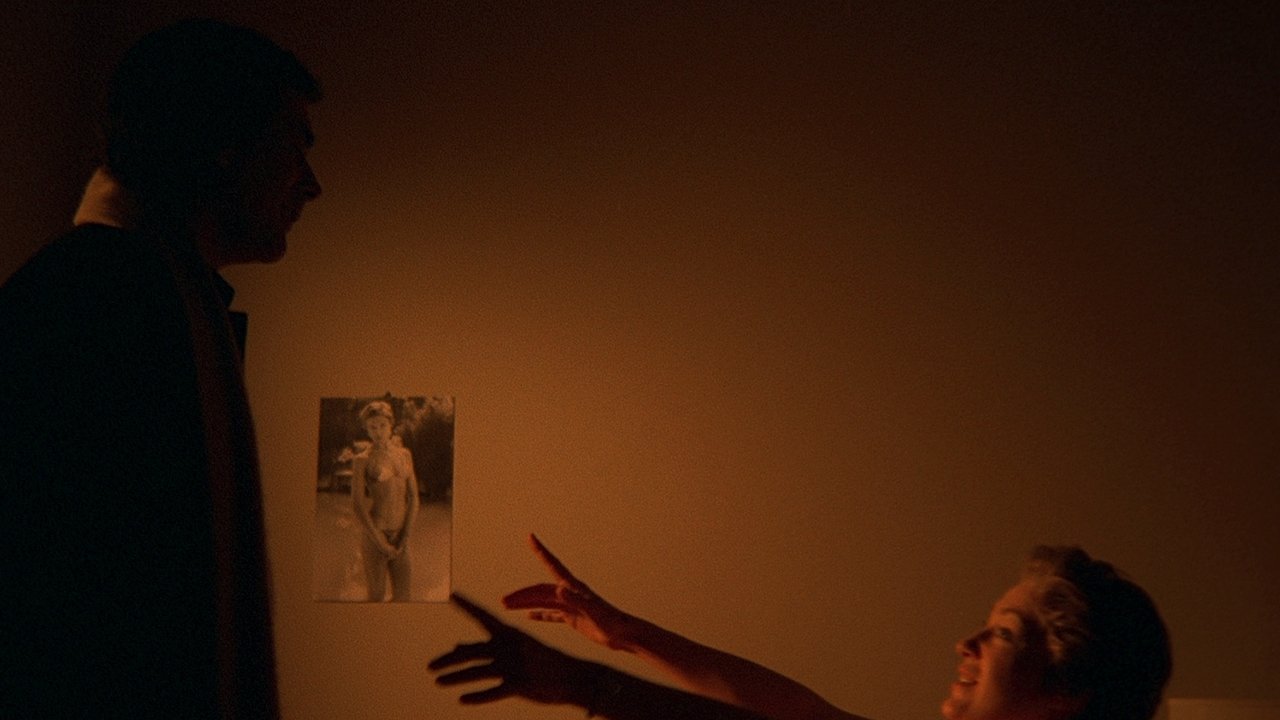

This isn't a plot-driven affair in the conventional sense. Antonioni, the master craftsman behind existential explorations like L'Avventura (1960) and the hypnotic mystery of Blow-Up (1966), is far more interested in the spaces between events, the unspoken tensions, the way environments reflect internal states. The film unfolds with his signature deliberate pace, demanding patience but rewarding it with meticulously composed shots where architecture – sleek, modern apartments, decaying palazzos, rain-slicked streets – speaks volumes about the characters' isolation. Reportedly, Antonioni returned to film in Italy after years abroad partly due to challenges securing funding for larger international projects, and perhaps this constraint focused his lens on these more intimate, internal landscapes. It would sadly be his last major solo feature before a stroke significantly impacted his ability to work.

Faces in the Fog

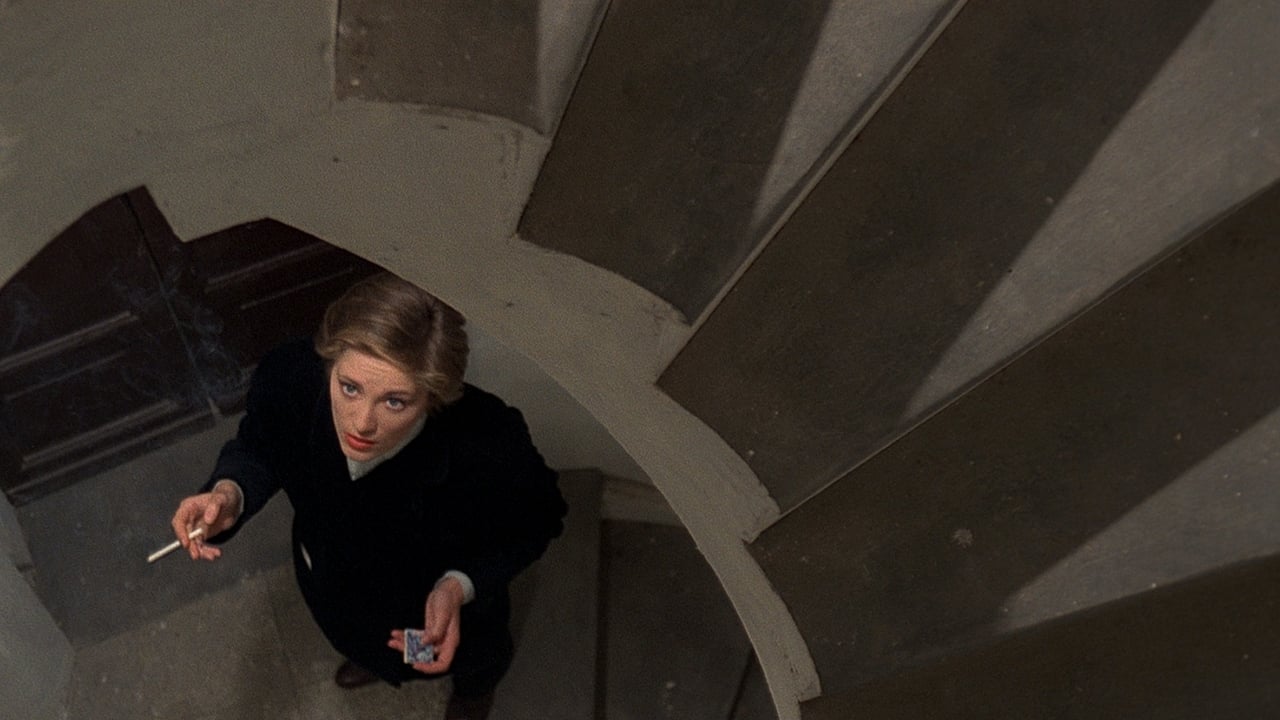

The women at the heart of Niccolò's search remain tantalizingly opaque. Mavi, portrayed by Daniela Silverio with a potent mix of vulnerability and patrician hauteur, is a creature of impulse and secrets, embodying a certain kind of elusive femininity that seems to both fascinate and repel Niccolò. Christine Boisson’s Ida offers a different kind of mystery – pragmatic, perhaps more self-aware, yet ultimately just as resistant to being fully known or possessed by Niccolò's gaze. Their performances are crucial; they aren't just objects of the director's quest but complicated individuals navigating their own desires and defenses within the world Antonioni constructs. Do we ever truly identify them? Or does the film suggest the limits of Niccolò's (and perhaps Antonioni's) perspective? It’s a question that hangs in the air, thick as that omnipresent fog.

And then there's Tomás Milián. Known to many of us VHS hounds for his intense roles in Spaghetti Westerns and gritty Poliziotteschi crime thrillers of the 70s, his casting here feels like a stroke of genius, apparently suggested by Bernardo Bertolucci after Antonioni's first choice, Gian Maria Volonté, wasn't available. Milián brings a weary physicality to Niccolò, his expressive face conveying a world of internal searching and frustration. He's not necessarily likable – often passive, observational, perhaps exploitative in his artistic detachment – but he is compellingly human in his adriftness. He embodies the film's central anxiety: the struggle to connect, to truly see another person beyond one's own needs and projections.

The Antonioni Aesthetic in the 80s

Visually, Identification of a Woman is pure Antonioni, yet filtered through an early 80s lens. The stark compositions, the use of negative space, the long takes – they're all here. But there’s also a distinct colour palette and a memorable, synth-heavy score by John Foxx (of Ultravox fame) that anchors it firmly in its era, creating a unique blend of timeless existential dread and period-specific atmosphere. Watching this on VHS, perhaps with the slightly softened image and muffled sound inherent to the format, almost adds another layer – the visual precision feels both heightened and slightly diffused, like recalling a dream.

The film famously won the 35th Anniversary Prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1982, a recognition of Antonioni's enduring artistry. Yet, it remains one of his less frequently discussed major works, perhaps due to its challenging ambiguity and its position late in his most prolific period. It doesn’t offer the narrative hooks of Blow-Up or the stark landscape poetry of Zabriskie Point (1970). Instead, it offers immersion in a mood, a state of being lost and searching.

Final Thoughts

Identification of a Woman isn't an easy watch, and it likely wasn't back when you might have stumbled upon its intriguing cover art in the 'Foreign Films' aisle. It demands engagement and offers few concessions to viewers seeking straightforward narrative resolution. Its portrayal of gender dynamics through Niccolò's perspective certainly invites critical discussion today. But as a work of cinematic art, a sustained exploration of alienation and the elusive nature of identity, it remains potent and visually arresting. It’s a film that gets under your skin, less through plot twists and more through its pervasive atmosphere and the haunting questions it poses about our ability to truly know ourselves or anyone else.

Rating: 8/10 - This score reflects the film's masterful craft, its atmospheric power, and its thought-provoking ambiguity. Antonioni's direction is typically precise and visually stunning, and Milián gives a deeply felt performance against type. It loses a couple of points purely because its deliberate pace and thematic density make it a challenging film that won't connect with all viewers, demanding significant patience and a willingness to embrace uncertainty – qualities that define its artistic strength but limit its casual accessibility.

What stays with you isn't a clear answer, but the feeling of Niccolò's search, the mist-shrouded cities, and the haunting sense that perhaps definitive identification, of oneself or another, is always just beyond reach.