There's a particular kind of chill that settles in while watching The Atomic Cafe (1982), a feeling distinct from the jump scares of horror or the manufactured suspense of a thriller. It’s the icy recognition of absurdity married to existential dread, delivered through the relentlessly cheerful, yet utterly terrifying, lens of America's own Cold War propaganda. This isn't a documentary that tells you what to think; it masterfully shows you, weaving together government films, newsreels, and atomic-era ephemera into a tapestry that's as darkly hilarious as it is profoundly disturbing. Watching it again now, decades after first encountering its flickering images on a worn VHS tape, that unsettling power hasn't faded one bit.

Found Footage, Found Fears

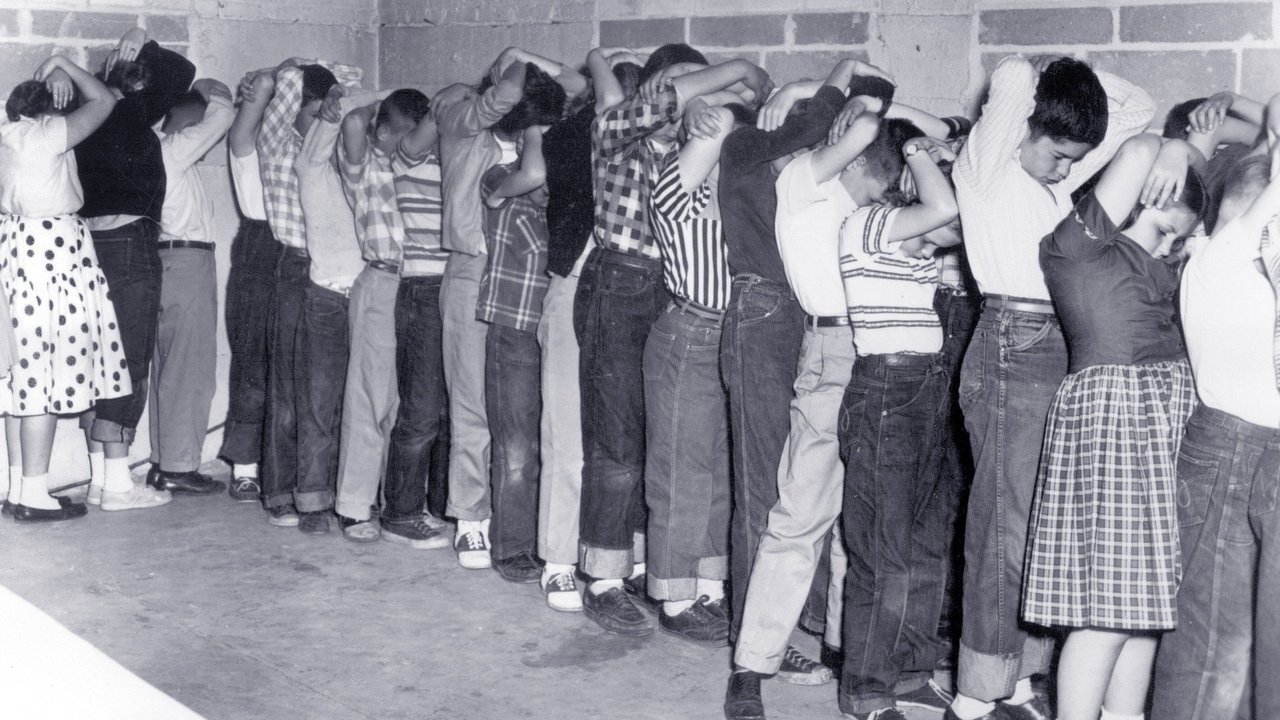

Compiled over years of meticulous archival digging by Kevin Rafferty, Jayne Loader, and Pierce Rafferty, The Atomic Cafe operates on a simple, devastating premise: let the historical record speak for itself. There’s no narrator guiding our interpretation, no modern-day talking heads offering perspective. Instead, we're immersed directly in the official messaging of the atomic age (roughly 1945-1965). We see chipper soldiers marching towards ground zero, reassuring families building fallout shelters stocked with canned goods, and perhaps most infamously, schoolchildren earnestly practicing "Duck and Cover" drills as if hiding under a flimsy wooden desk could possibly ward off nuclear annihilation.

The genius lies in the curation and juxtaposition. A clip demonstrating the awesome, terrifying power of an H-bomb test might be followed immediately by a jaunty, utterly surreal pop song about atomic energy, or an army training film nonchalantly explaining acceptable radiation exposure levels. The effect is cumulative, building a portrait of a nation simultaneously obsessed with, terrified by, and bizarrely casual about the prospect of Armageddon. I distinctly remember renting this back in the day, maybe from one of those smaller neighborhood video stores with handwritten labels, expecting perhaps a dry history lesson, and getting... well, this. It felt less like watching a movie and more like discovering a hidden, uncomfortable truth.

The Cut is the Commentary

Without spoken narration, the editing becomes the directorial voice. The Raffertys and Loader demonstrate an incredible skill for sequencing clips to expose inherent contradictions and black humor. They aren't mocking the past so much as holding up a mirror to its official self-representation, revealing the cracks in the facade. Think about the sequence featuring Paul Tibbets, pilot of the Enola Gay, calmly recounting the bombing of Hiroshima, intercut with boosterish newsreels celebrating America's atomic might. The lack of explicit comment makes the implicit horror all the more potent.

It's fascinating to consider the sheer effort involved. This wasn't the digital age; the filmmakers painstakingly sifted through mountains of physical film reels housed in places like the National Archives and military film libraries, searching for just the right moments. The result feels less constructed and more excavated, like unearthing artifacts from a deeply strange, almost alien civilization that happens to be our own recent past. The soundtrack, too, plays a crucial role, filled with forgotten atomic-themed novelty songs ("Atomic Cocktail," anyone?) that provide a bizarrely upbeat counterpoint to the potentially world-ending subject matter.

Faces in the Fallout

While there are no traditional "performances," the film is filled with unforgettable faces captured in the archival footage. There’s the unnerving blankness in the eyes of soldiers ordered to witness nuclear tests up close, the forced smiles of families posing in their backyard bomb shelters, the earnest belief of civil defense authorities explaining utterly inadequate survival strategies. These aren't actors; they are real people caught in the gears of history and propaganda, their reactions ranging from gung-ho patriotism to quiet, bewildered fear. Seeing Bert the Turtle advise children to "Duck and Cover!" feels almost like a fever dream now, but it was presented with deadly seriousness back then. Doesn't that disconnect resonate with how seemingly absurd dangers are sometimes presented even today?

Legacy of the Mushroom Cloud

Released in 1982, The Atomic Cafe landed right as Cold War tensions were experiencing a significant resurgence under the Reagan administration. Its timing couldn't have been more pointed, offering a stark reminder of the atomic anxieties that had perhaps been suppressed but never truly disappeared. It garnered critical acclaim for its unique approach and chilling effectiveness, becoming a cornerstone of documentary filmmaking focused on archival compilation. While produced on a shoestring budget, its impact far outweighed its cost, forcing viewers to confront the unsettling legacy of the atomic age through the very materials designed to soothe public fears. Its influence can be seen in later documentaries that rely heavily on found footage to deconstruct official narratives. What lingers most after the film ends isn't just the imagery of the mushroom cloud, but the pervasive sense of carefully manufactured reality beginning to fray at the edges.

Rating: 9/10

The Atomic Cafe earns a high score not for being traditionally "entertaining," but for its stunning artistic achievement and enduring power. Through masterful editing and fearless curation of archival material, it creates a unique and unforgettable cinematic experience – a darkly funny, deeply unsettling, and absolutely essential look at how a nation grappled (or failed to grapple) with the unthinkable. It uses the tools of propaganda to dismantle propaganda itself, leaving the viewer with a profound sense of unease and a barrage of haunting images.

This film is a potent time capsule, a masterclass in documentary form, and a chilling reminder of anxieties that still echo beneath the surface. It’s one of those VHS finds that truly sticks with you, long after the tape has been rewound.