He writes letters. Taunting, arrogant letters filled with grammatical errors that somehow make them even more chilling. He strips naked before he kills, a ritualistic shedding of the last vestiges of humanity before the plunge. Warren Stacy, the antagonist of J. Lee Thompson’s 1983 thriller 10 to Midnight, isn't just a movie monster; he feels like a raw nerve exposed, a terrifyingly plausible predator hiding behind a blandly handsome face. Watching this film again, decades later, that uncomfortable intimacy with the killer’s pathology still manages to burrow under the skin.

### Cold Fury, Calculated Cruelty

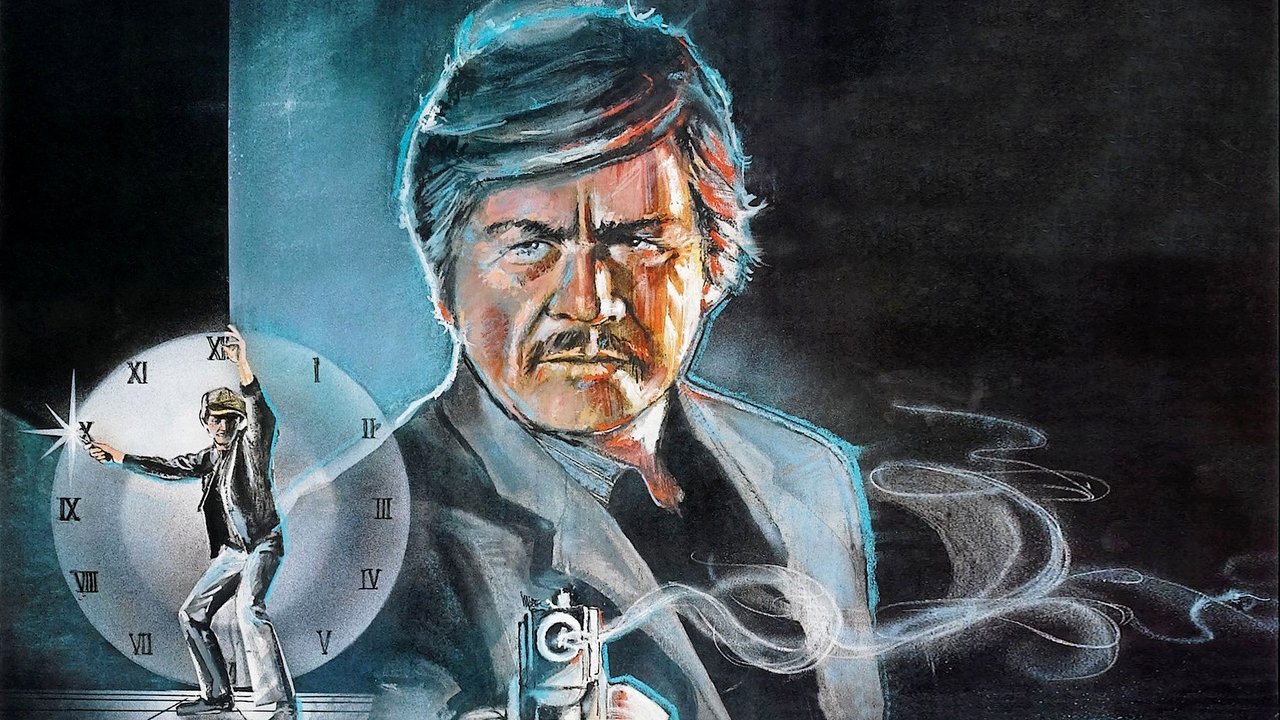

At the center of the storm is Charles Bronson as Leo Kessler, a cynical LAPD detective whose granite-faced weariness feels particularly earned here. This isn't the gleeful vigilante of Death Wish. Kessler is older, more tired, and pushed to a breaking point by a legal system that seems designed to protect predators like Stacy (Andrew Stevens) rather than his victims. When Stacy meticulously constructs alibis and exploits loopholes, Kessler’s frustration boils over into outright fury, leading him down a morally treacherous path. Bronson, reunited again with director Thompson (who guided him through several films, including Death Wish 4), embodies this simmering rage perfectly. It’s a performance less about righteous anger and more about bone-deep exhaustion with evil.

The film courted considerable controversy upon release, and it's easy to see why. Produced by the infamous Cannon Group (run by Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, kings of 80s action and exploitation), 10 to Midnight doesn’t shy away from the ugliness of its subject matter. The violence against women is frequent and depicted with a bluntness that feels both shocking and, at times, uncomfortably gratuitous. There’s a persistent rumour, often repeated in fan circles, that Bronson himself strongly objected to the level of nudity Thompson insisted on, feeling it tipped into exploitation rather than necessary grit. Whether strictly true or embellished lore, it speaks to the film’s undeniable sleaze factor, a hallmark of certain Cannon productions that walked a fine line between gritty realism and outright sensationalism.

### That Creep Next Door

What elevates 10 to Midnight above standard exploitation fare, however, is the genuinely unnerving performance by Andrew Stevens as Warren Stacy. Drawing alleged inspiration from the chilling methodologies of real-life killers like Ted Bundy and Richard Speck, Stevens crafts a character whose polite, almost charming exterior makes his sudden descents into violence all the more jarring. He’s the guy who helps carry your groceries, then later fantasizes about tearing you apart. This juxtaposition is the film’s dark heart. The scenes where Stacy stalks his prey, often observed from his apartment window, are thick with a voyeuristic dread that Thompson’s workmanlike direction captures effectively. Did his quiet menace send a shiver down your spine back in the day? It certainly holds up as unsettlingly plausible.

Supporting turns, like Lisa Eilbacher as Kessler's daughter Laurie (who inevitably becomes entangled with the case), add necessary human stakes. Her terror feels authentic, grounding the more outlandish procedural elements. The dynamic between Kessler and his younger, by-the-book partner Paul McAnn (Geoffrey Lewis adds reliable character support in a smaller role) highlights the central conflict: adhere to the law even when it fails, or break it to ensure justice is served?

### Production Grime and Retro Fun Facts

- Inspired by Darkness: As mentioned, the filmmakers reportedly looked towards the chilling patterns of real serial killers like Richard Speck (mass murder in a nurse dormitory) and Ted Bundy (charm masking psychopathy) when crafting Warren Stacy's character and methods. This grounding, however loose, adds a layer of disturbing realism.

- Cannon Fodder: Made for approximately $4.6 million (around $14 million today), 10 to Midnight was a solid box office success for Cannon Films, grossing over $7 million domestically. It fit perfectly into their slate of gritty, star-driven genre pictures that filled video store shelves throughout the 80s.

- Script Doctoring: The original script was apparently a more straightforward police procedural. It was significantly rewritten to tailor it to Charles Bronson's established screen persona and to inject the controversial vigilante and exploitation elements that Cannon favoured.

- Location, Location, Brutality: Much of the film was shot on location in Los Angeles, using real apartments and streets to enhance the gritty, urban atmosphere. The choice of mundane settings for Stacy's attacks amplifies the sense that this kind of horror could erupt anywhere.

The film utilizes its Los Angeles setting well, capturing a specific early-80s urban decay that feels both dated and timelessly dangerous. The score is typical of the era – synth-heavy, sometimes intrusive, but occasionally effective at ratcheting up the tension during stalk sequences. It’s not subtle filmmaking, but Thompson, a veteran craftsman, knows how to stage a suspenseful set piece, even if the overall package feels undeniably grimy.

### The Verdict

10 to Midnight is a tough, nasty piece of work. It’s a film that wallows in the darkness it portrays, often blurring the line between condemning violence and exploiting it. Bronson delivers a solid, weary performance, and Andrew Stevens is genuinely chilling as the killer. The central ethical dilemma gives it slightly more substance than a standard slasher, exploring the frustrations of law enforcement against calculated evil. However, its heavy reliance on female nudity and brutal violence feels undeniably problematic and exploitative by today's standards, and frankly, felt questionable even then. It’s an effective, often gripping thriller, but one coated in a layer of sleaze that’s hard to wash off.

Rating: 6/10

Justification: The film earns points for Bronson's grounded performance, Stevens' truly unnerving portrayal of the killer, and its effective generation of gritty tension and dread. It successfully taps into contemporary fears about random urban violence. However, it loses significant points for its often excessive and exploitative use of nudity and violence against women, which frequently feels gratuitous rather than essential to the narrative. The script also has its share of procedural clichés and occasionally clumsy dialogue, preventing it from reaching the heights of truly great thrillers. It’s a potent, if problematic, slice of 80s Cannon grit.

Final Thought: More than just another Bronson vehicle, 10 to Midnight remains a potent and disturbing artifact of early 80s anxieties, capturing a specific brand of urban fear and vigilante frustration, all wrapped up in the signature, often controversial, style of Cannon Films. It's a grim reminder from the VHS shelves that sometimes the most frightening monsters are the ones who smile right at you.