Silence. That’s the first thing that strikes you, settles over you like the dust coating the ruins in Luc Besson’s striking debut feature, The Last Battle (Le Dernier Combat). In a genre often defined by noisy explosions and frantic chases, this 1983 French post-apocalyptic vision presents a world where humanity has not only lost its civilization but, mysteriously, its ability to speak. It’s a bold, unsettling premise, one that forces the film, and the viewer, to rely entirely on the visual, the physical, the purely cinematic.

Watching it again after all these years, possibly fished out from a dusty corner of the memory palace that used to be the video rental store, its power hasn't diminished. If anything, its starkness feels even more potent today.

A World Seen, Not Heard

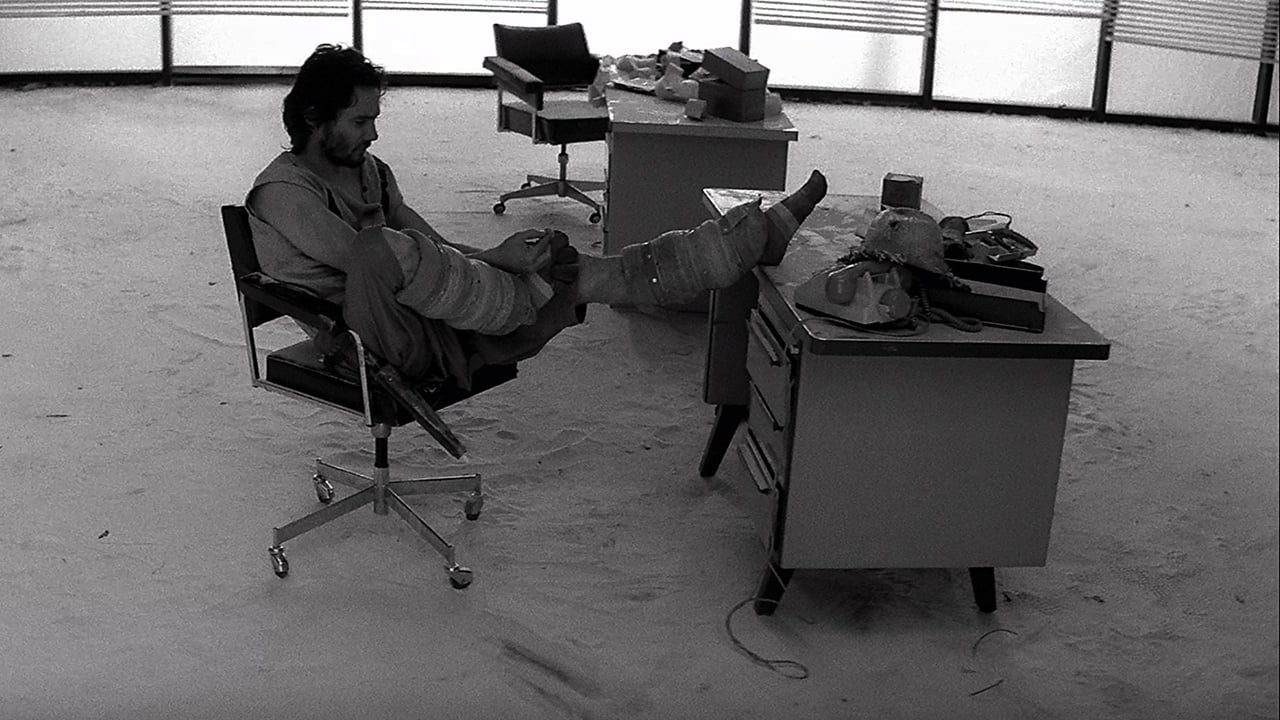

Shot in stark, high-contrast black and white CinemaScope – an ambitious choice for a low-budget first film – The Last Battle immediately establishes a desolate beauty. We follow 'The Man' (Pierre Jolivet, who also co-wrote the screenplay with Besson), navigating a shattered Parisian landscape. Buildings crumble, winds howl through deserted streets, and survival is a grim, solitary affair. The cause of the apocalypse is never explained; all we know is that rain brings death, and communication is reduced to grunts, gestures, and the occasional, desperate cry.

The lack of dialogue isn't a gimmick; it's the film's core concept. It forces Besson, barely in his early twenties, to rely purely on visual storytelling. And largely, he succeeds. Every glance, every movement, every confrontation carries immense weight. We understand The Man's ingenuity as he cobbles together a makeshift aircraft, his longing for connection, his fear of 'The Brute' (Fritz Wepper), a menacing scavenger who embodies the loss of humanity. It’s a testament to the fundamental power of images, something Besson would continue to explore, albeit with more gloss and dialogue, in later films like Nikita (1990) and Léon: The Professional (1994).

Primal Actions, Human Traces

The performances are necessarily physical. Jolivet carries the film with a compelling blend of resourcefulness and vulnerability. His journey leads him to a derelict hospital, where he encounters a weary doctor (Jean Bouise, a wonderful French character actor) who seems to be guarding the last vestiges of civility – and perhaps, the last woman (Christine Boisson). Bouise brings a quiet dignity to his role, a flicker of the old world resisting the encroaching savagery. Their interactions, tentative and unspoken, form the fragile heart of the film. Can trust exist? Can care endure when words fail? These questions hang heavy in the charged silence.

The film’s low budget, reportedly scraped together for around $500,000 (a pittance even then), is evident but often turned into a strength. The desolate locations – reportedly including abandoned construction sites around Paris – feel chillingly authentic. The production design, though sparse, effectively conveys a world scavenged and repurposed. There's an undeniable resourcefulness here, a rawness that feels appropriate to the subject matter. This wasn't a slick Hollywood production; it felt like a desperate broadcast from the end of the world itself, discovered on a worn-out VHS tape. Besson apparently expanded the film from his own earlier short, L'Avant Dernier (1981), retaining its core visual ideas and bleak atmosphere.

Echoes in the Wasteland

While not packed with action in the conventional sense, the film has moments of startling violence and tension. The confrontation between The Man and The Brute feels primal and inevitable. Yet, it’s the quieter moments that linger: The Man attempting to share a scavenged meal, the Doctor tending to his patient, the fleeting glimpses of hope amidst the decay. It taps into something fundamental about human needs – companionship, security, a reason to keep going when everything seems lost. Doesn't that struggle resonate, even without the apocalyptic setting?

The Last Battle isn't a comfortable watch. It’s bleak, minimalist, and demands patience. Its deliberate pacing and lack of exposition might frustrate some viewers expecting more conventional thrills. But for those willing to immerse themselves in its unique atmosphere, it’s a haunting and strangely beautiful piece of filmmaking. It feels like a crucial stepping stone, not just for Besson, but for a certain kind of visually driven, atmospheric sci-fi that occasionally surfaced in the 80s, standing apart from the more bombastic fare. It garnered attention on the festival circuit, winning awards and signaling the arrival of a distinctive new voice in French cinema.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's striking artistic vision, its bold commitment to visual storytelling, and its powerful atmosphere, all achieved under significant constraints. The minimalist approach is incredibly effective, and the performances convey volumes without words. It’s a challenging but rewarding experience, a true standout from the era for its sheer audacity and haunting imagery, even if its deliberate pace might not connect with everyone.

The Last Battle remains a stark reminder that sometimes, the most profound statements are made without uttering a single word. What lingers most is the silence, and the question of what truly defines us when language fails.