### The Unblinking Eye: Reflecting on The Prize of Peril (1983)

There’s a chilling moment early in Yves Boisset’s Le Prix du Danger – known to Anglophone audiences as The Prize of Peril – where the sheer, ghastly premise settles in. It’s not presented with futuristic lasers or cybernetic hunters, but with a kind of grim, bureaucratic nonchalance. A wildly popular television show where a desperate contestant is hunted through city streets by trained killers, all for ratings and a cash prize. Watching it again now, decades after first encountering its stark vision on a worn VHS tape, the film feels less like science fiction and more like a documentary delivered thirty years too early. What does it say about us that this French thriller from 1983 feels startlingly relevant to the media landscape we inhabit today?

A Game We Shouldn't Want to Watch

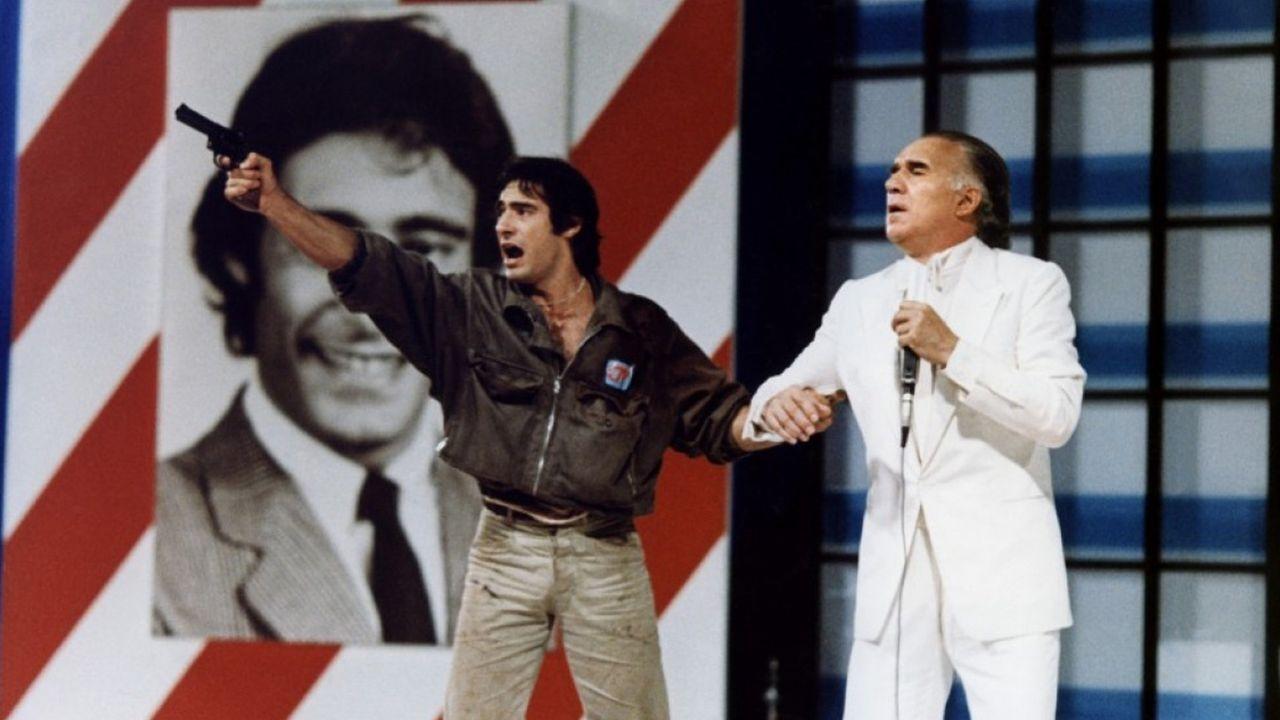

Based on Robert Sheckley's prescient 1958 short story, the film drops us into a near-future society glued to their screens, awaiting the next episode of "Le Prix du Danger". Our contestant, François Jacquemard, played with a desperate, physical intensity by Gérard Lanvin, is an unemployed man pushed to the brink. He sees the million-dollar prize not just as wealth, but as escape, as validation. Opposing him aren't just the five hunters, but the entire machinery of the show, masterminded by the icily charming host Frédéric Mallaire (Michel Piccoli, radiating cynical detachment) and the ambitious producer Laurence Ballard (Marie-France Pisier, portraying a fascinating blend of calculation and perhaps buried conscience). The setup is simple, brutal, and terrifyingly plausible.

What sets The Prize of Peril apart from some of its American counterparts is its distinctly European flavour. Director Yves Boisset, known for his politically charged thrillers, crafts a film that’s less about explosive set pieces and more about sustained tension and biting social commentary. Filmed largely on location in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (doubling for a grim near-future France), the urban landscape feels authentically decaying, a stark contrast to the slick, manipulative gloss of the television studio. The chase sequences are gritty and grounded, emphasizing Jacquemard's vulnerability and exhaustion rather than superhuman feats. There’s a rawness here, a lack of Hollywood polish that makes the violence feel genuinely disturbing, not merely spectacular.

Faces in the Crowd, Staring Back

The performances are key to the film's unsettling power. Gérard Lanvin embodies the everyman pushed into an impossible corner. His desperation is palpable, etched onto his face as he runs, hides, and fights. You feel the exhaustion, the fear, the flickering moments of hope almost immediately extinguished. He’s not an action hero; he’s prey, and Lanvin makes you believe it. Opposite him, Michel Piccoli is simply masterful. His Mallaire is the epitome of media cynicism – suave, unflappable, utterly devoid of empathy, treating human lives as mere variables in an entertainment equation. His smiles never quite reach his eyes, and his soothing voice masks a chilling emptiness. And Marie-France Pisier, an actress always capable of conveying complex inner lives, gives Ballard layers that prevent her from being a simple villain. You see the ambition, yes, but also flashes of awareness, maybe even regret, quickly suppressed in service of the show's success.

Truth Stranger Than Fiction?

It’s impossible to discuss The Prize of Peril without acknowledging its place in the lineage of "deadly game show" narratives. It followed the 1970 West German TV film Das Millionenspiel (also based on Sheckley's story) and, perhaps most famously, preceded the Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle The Running Man (1987), which was based on a 1982 novel by Stephen King (as Richard Bachman). The similarities between The Prize of Peril and The Running Man were so striking that Sheckley successfully sued the producers of the latter for plagiarism, resulting in an out-of-court settlement. Watching Boisset's film, you can see why. While The Running Man leans heavily into bombastic action and colourful villains, The Prize of Peril feels grittier, more cynical, and perhaps ultimately, more disturbing because its horrors feel depressingly achievable. There's a fascinating piece of trivia here: the core concept, born in the late 50s, adapted earnestly in Germany in 1970, given a cynical French twist in '83, and then blown up into Hollywood spectacle in '87. It charts a strange course through media history itself.

I remember renting this one, probably drawn by the intriguing cover art common to many European sci-fi/thrillers that found their way onto North American shelves. It wasn't the explosive action promised by some contemporaries, but something stickier, more thought-provoking. It felt dangerous in a way few films did back then.

The Reflection in the Screen

Beyond the chase, The Prize of Peril forces uncomfortable questions. Who is truly responsible for the horror unfolding? The network executives? The smiling host? The hunters pulling the triggers? Or is it the audience, consuming the spectacle with morbid fascination? Boisset repeatedly cuts to shots of viewers – families, couples, individuals – utterly captivated by Jacquemard's televised ordeal. Their passive consumption enables the entire grotesque enterprise. Doesn't this dynamic echo, albeit in a less lethal form, the culture surrounding reality television and online outrage today? The film suggests that the line between entertainment and exploitation is terrifyingly thin, and easily blurred when ratings and profit are the primary motivators. What does it say about our own appetites, that variations of this theme continue to resonate so strongly?

The film isn't perfect. Some of the social commentary can feel a little on-the-nose by today's standards, and the pacing might test viewers accustomed to more frantic editing. Yet, its core message remains incredibly potent. It captures a specific kind of late Cold War, pre-internet anxiety about media power and societal decay, filtered through a tense, well-acted thriller framework.

***

VHS Heaven Rating: 8/10

Justification: The Prize of Peril earns a strong 8 for its chilling prescience, its gritty and grounded execution, and its powerhouse performances, particularly from Piccoli and Lanvin. It tackles its satirical themes with intelligence and bite, creating a truly unsettling atmosphere that lingers long after the credits roll. While perhaps less known than The Running Man, its starker, more cynical vision arguably cuts deeper and feels unnervingly relevant decades later. It loses a couple of points for occasional heavy-handedness in its messaging and pacing that might feel slightly dated to some.

Final Thought: Decades before "reality TV" became a ubiquitous term, The Prize of Peril held up a dark mirror, asking if we'd watch someone die for entertainment. The most uncomfortable part? It never felt entirely sure we'd say no.