The air in 2017 crackles with paranoia, thick and heavy like the static hiss from an old CRT after midnight. Conception itself is a crime against the state, punishable by consignment to the deepest hole imaginable: the Fortress. This isn't just concrete and razor wire; it's a subterranean nightmare burrowed into the earth, a high-tech panopticon run by the chillingly bureaucratic Men-Tel corporation. Welcome, inmate, your body is no longer your own. Fortress (1992) throws us headfirst into this bleak future, a film that arrived on VHS shelves promising sci-fi action but delivered a surprisingly grim and inventive slice of dystopian dread.

Maximum Security, Minimum Hope

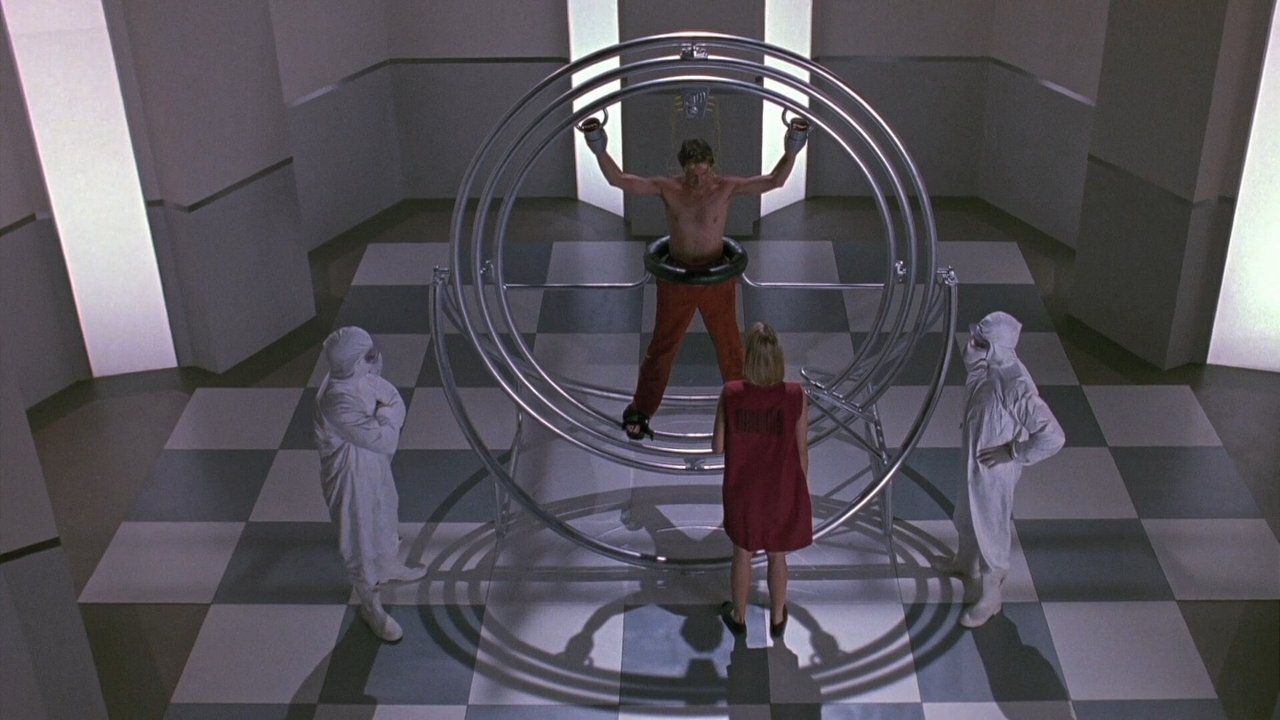

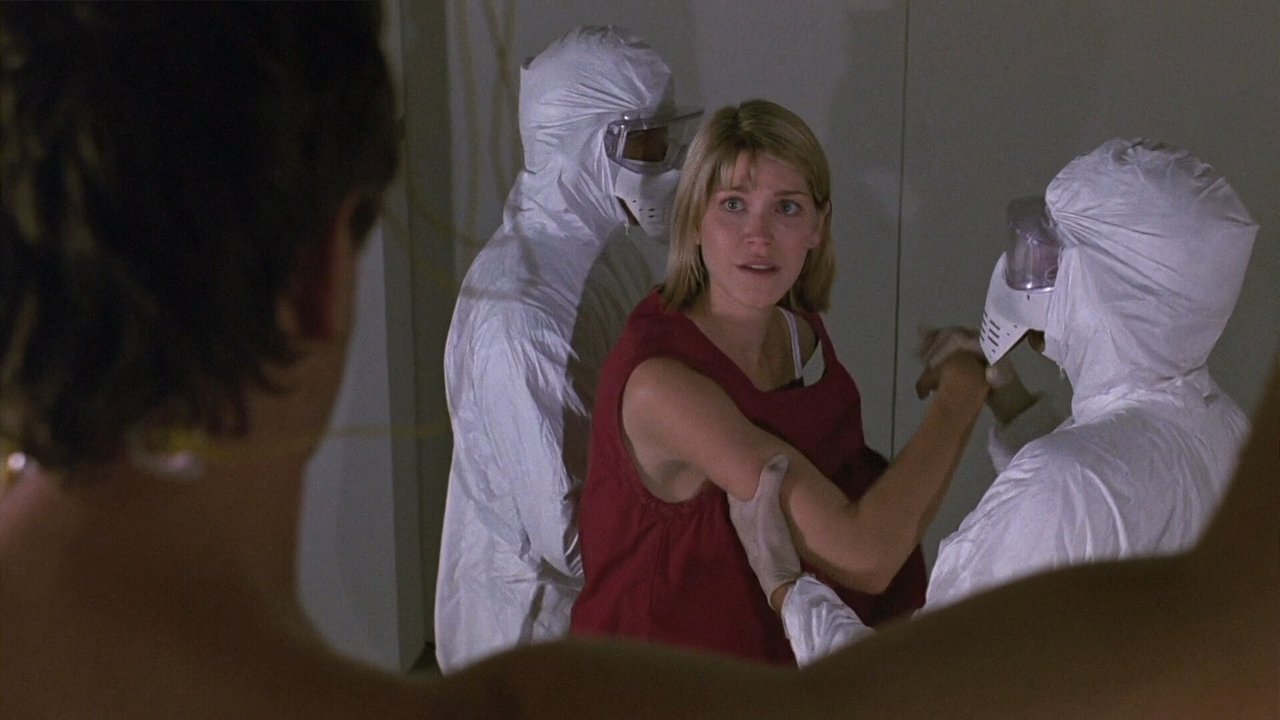

From the moment John Brennick (Christopher Lambert) and his wife Karen (Loryn Locklin) are caught trying to cross the border after an illegal second pregnancy, the film establishes an oppressive atmosphere. Director Stuart Gordon, a filmmaker who knew a thing or two about making audiences squirm after unleashing Re-Animator (1985) and From Beyond (1986) upon the world, doesn't shy away from the inherent body horror of the premise. The Fortress isn't just inescapable; it's invasive. Each prisoner is implanted with an "Intestinator," a nasty piece of bio-tech designed to inflict agony or euphoria at the whim of the warden, remotely triggered for any transgression – crossing designated laser lines, unauthorized thoughts detected by "mind probes," or simply displeasing the powers that be. Doesn't that core concept still feel unnervingly relevant?

The Cold Glare of Authority

Presiding over this technological hellhole is Director Poe, played with magnificent, understated menace by Kurtwood Smith. Fresh off searing his image into our minds as the ruthless Clarence Boddicker in RoboCop (1987), Smith crafts Poe not as a raving despot, but as a precisely controlled, almost corporate sociopath. He speaks in measured tones, observes his charges through screens like specimens, and sees the Fortress and its populace as his personal, perverse experiment. His interactions with Zed-10, the central computer system that monitors everything down to prisoner dreams, are highlights of cold, calculated villainy. You just know this guy colour-codes his spreadsheets of human misery. Smith’s performance elevates the material, providing a genuinely unsettling antagonist who feels less like a cartoon villain and more like the terrifyingly plausible face of futuristic totalitarianism.

Lambert in the Labyrinth

Christopher Lambert, arguably at the peak of his action hero fame following the Highlander series, anchors the film as the stoic Brennick. He’s the archetypal reluctant hero, a former Black Beret officer whose only crime was wanting a family. Lambert brings his signature gravelly voice and intense gaze to the role, effectively portraying a man pushed to his absolute limit. While not his most nuanced performance, he’s utterly convincing as a resourceful survivor navigating the deadly politics and brutal realities of the prison. I remember renting this Fortress tape back in the day, maybe expecting Highlander in the future, but finding Lambert grappling with something far more psychologically invasive. He grounds the film's more outlandish concepts in a relatable human struggle for freedom and reunion.

Grinding Gears and Practical Grit

What truly makes Fortress a standout gem from the VHS era is its commitment to practical effects and tangible world-building. Filmed largely on location in Queensland, Australia, at the Village Roadshow Studios (including inside their massive water tank for some sequences!), the production design creates a truly unique and imposing environment. The Fortress itself, a multi-level structure dominated by laser grids, sterile corridors, and cramped, shared cells, feels genuinely claustrophobic. The effects, from the gut-churning Intestinator sequences (achieved with clever physical effects and prosthetics) to the imposing "Strike Clone" security robots, possess a tactile quality often missing in today's CGI-heavy landscape. Remember how those shimmering laser walls felt genuinely dangerous back then? The film was made for a relatively modest $12 million but managed to gross over $40 million worldwide, proving its blend of sci-fi horror and action struck a chord. Gordon masterfully uses these elements, building tension not just through action beats but through the constant, technologically enforced threat hanging over every inmate.

Escaping the System

Of course, this being a 90s action flick starring Lambert, an escape is inevitable. The film delivers on this front, staging some tense and inventive sequences as Brennick allies with fellow inmates (including memorable turns from Jeffrey Combs, Gordon's frequent collaborator, and Vernon Wells) to find a way out. The plot twists and turns, incorporating elements of corporate espionage, cyborg guards, and dream invasion, keeping the pace brisk. While some aspects feel undeniably pulpy, the underlying grimness and the stakes – losing not just your life, but control over your own body and mind – remain potent. It’s a testament to the film’s effectiveness that even amidst the explosions and laser fire, the core dread never fully dissipates.

Still Standing?

Fortress might have aged in some respects – the vision of 2017 is amusingly off, and some of the tech looks quaint now – but its core themes of surveillance, bodily autonomy, and corporate overreach feel more relevant than ever. It spawned a direct-to-video sequel, Fortress 2: Re-Entry (2000), which lacked the original's spark and grit. But the first film remains a tightly constructed, often brutal, and surprisingly thoughtful sci-fi actioner. It perfectly captured that early 90s vibe where practical effects reigned, dystopian futures felt chillingly plausible, and Stuart Gordon could reliably deliver genre thrills with an edge.

Rating: 7/10

The score reflects a film that punches well above its B-movie weight class. Strong performances, particularly from Kurtwood Smith, a genuinely unsettling core concept, impressive practical effects, and Stuart Gordon's assured direction make it highly memorable. It's hampered slightly by some predictable plot beats and occasionally clunky dialogue, but its atmosphere and inventive cruelty leave a lasting impression. Fortress is a prime example of the kind of dark, imaginative sci-fi that thrived on video store shelves – a gritty, sometimes uncomfortable, but ultimately rewarding watch that still holds a certain chilling power decades later. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the most terrifying prisons aren’t made of bars, but of bytes and invasive code.