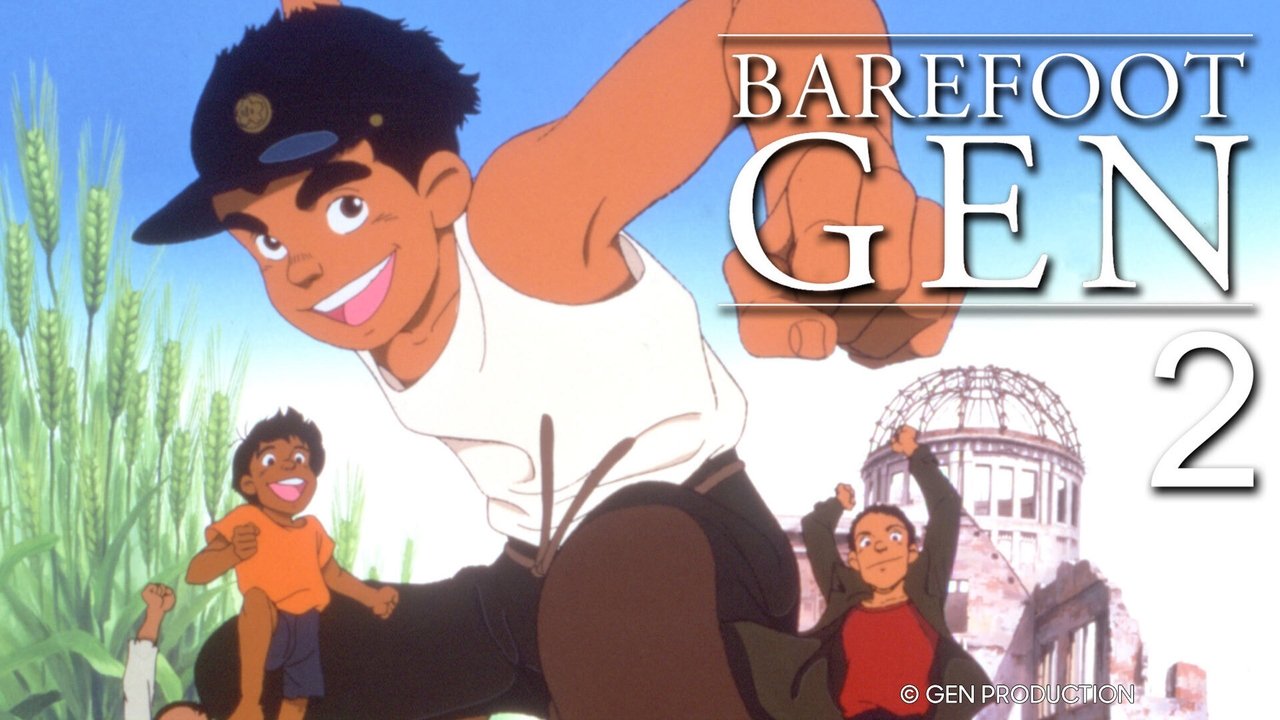

Here we go again, pulling another tape from the shelf here at "VHS Heaven". This time, it’s one that doesn’t exactly scream “Friday night popcorn flick.” Some films, even animated ones from an era often associated with vibrant adventures, carry a weight that settles deep in your bones long after the VCR clicks off. Barefoot Gen 2 (1986) is undeniably one of those films. It picks up where its predecessor left off, not just in narrative, but in its unflinching gaze into the abyss of human suffering and survival.

Three Years After the Flash

If the first Barefoot Gen (1983) was the initial, raw scream of agony following the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, this sequel explores the festering wound. We rejoin young Gen Nakaoka in 1948, three years after the horrific blast that claimed most of his family. The immediate chaos has subsided, replaced by the grinding struggle of daily life in the ruins. Food is scarce, sickness (the insidious radiation poisoning) lingers like a phantom menace, and the social fabric is frayed, revealing both the best and worst of humanity trying to rebuild from literal ashes. Directed once again by Toshio Hirata, who had also helmed the first film, Barefoot Gen 2 continues the adaptation of Keiji Nakazawa's deeply personal manga – a chronicle born from Nakazawa's own harrowing survival of the bombing. You can feel Nakazawa’s lived experience embedded in every frame; this isn't just historical fiction, it's testimony.

Survival's Sharper Edges

What strikes you immediately about Barefoot Gen 2 is how the landscape of survival has shifted. The shock has worn off, replaced by a grim pragmatism. Gen, voiced with unwavering spirit by Issei Miyazaki, is older, tougher, but still fiercely protective of his surviving mother Kimie (Yoshie Shimamura) and the group of war orphans he essentially adopts. The film doesn't shy away from the darker aspects of this period – the desperation leading to crime, the social ostracization of survivors, the heartbreaking physical deterioration caused by radiation. There's a particularly harrowing subplot involving Ryuta (Masaki Kōda), one of the orphans, that underscores the impossible choices faced by children forced to grow up too fast in a world shattered by adult conflict. It’s a stark reminder of how war’s consequences ripple outwards, poisoning years and lives long after the fighting stops. Doesn't this prolonged aftermath, the slow erosion of hope and health, sometimes feel even more devastating than the initial cataclysm?

Animation as Witness

The animation style, typical of 80s anime, might seem incongruous at first glance with the subject matter. The character designs retain a certain roundness, a visual echo of the manga source. Yet, Toshio Hirata wields this style effectively. The moments of normalcy – children playing, small acts of kindness – stand in sharper contrast to the sudden intrusions of horror: the discovery of skeletal remains, the visible signs of radiation sickness, the stark poverty. It's not graphically gratuitous in the way the first film depicted the bombing itself, but its emotional impact is arguably just as potent, focusing on the slow, grinding devastation. There’s a deliberate quality to the direction, forcing us to bear witness alongside Gen. We aren't spared the ugliness, nor the flickers of persistent humanity. This commitment to Nakazawa's truth is likely why these films, often discovered on worn VHS tapes perhaps rented alongside more typical fare, left such an indelible mark on Western audiences unfamiliar with this kind of animated storytelling. It served as a powerful counter-narrative to the often sanitized versions of history.

A Legacy Etched in Pain and Perseverance

Like its predecessor, Barefoot Gen 2 wasn't a massive box office hit, especially internationally where its distribution was often limited to specialty video labels. Yet, its importance transcends ticket sales. It stands alongside Studio Ghibli's Grave of the Fireflies (1988) as essential, albeit incredibly difficult, viewing within anime's exploration of war's true cost. It’s interesting to note that Keiji Nakazawa remained deeply involved, ensuring the anime stayed true to the spirit and events of his manga, which itself ran for years, chronicling Gen's life well beyond the scope of the two films. These films serve as a vital, accessible entry point into his monumental work. They remind us, particularly those of us who grew up during the Cold War's lingering shadow, of the very real human stakes behind the abstract concepts of nuclear conflict. I remember finding a copy at a local rental store tucked away in the animation section, completely unprepared for the emotional weight it carried. It was a formative experience, demonstrating animation's power to tackle the most profound and painful subjects.

The performances, particularly Issei Miyazaki's Gen, are central to the film's power. He captures the character's fierce determination, his moments of despair, and his unwavering loyalty without resorting to melodrama. Yoshie Shimamura as Kimie conveys the quiet agony and resilience of a mother trying to hold onto hope amidst unimaginable loss. Their struggles feel achingly real.

Final Reflection

Barefoot Gen 2 is not an easy watch. It's emotionally draining, heartbreaking, and forces confrontation with horrific historical realities. But it's also a testament to the resilience of the human spirit, the importance of community, and the enduring power of hope, even when flickering faintly in the darkest ruins. It avoids easy answers and sentimentality, offering instead a raw, honest portrayal of life after catastrophe.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's profound emotional impact, its historical significance as a direct continuation of Keiji Nakazawa's testimony, and its unflinching commitment to portraying the difficult truth of Hiroshima's aftermath. While harrowing, its artistic merit and importance as an anti-war statement are undeniable. It’s a film that stays with you, a necessary albeit painful reminder etched onto celluloid, and later, onto those magnetic tapes we once held in our hands. What does it ask of us, the viewers, decades later, having witnessed Gen’s struggle? Perhaps simply to remember.