It starts with such an audacious, almost unbelievable proposition, doesn't it? A classified ad seeking a companion – a 'wife' – for a year of self-imposed exile on a remote tropical island. Watching Nicolas Roeg's Castaway (1986) again after all these years, that central conceit feels even more stark, a bizarre social experiment masquerading as escapist fantasy. It's a film that likely caught many an eye scanning the shelves of the local video store, perhaps promising sun, sea, and romance, only to deliver something far more raw, complex, and profoundly unsettling.

Paradise Found, Paradise Questioned

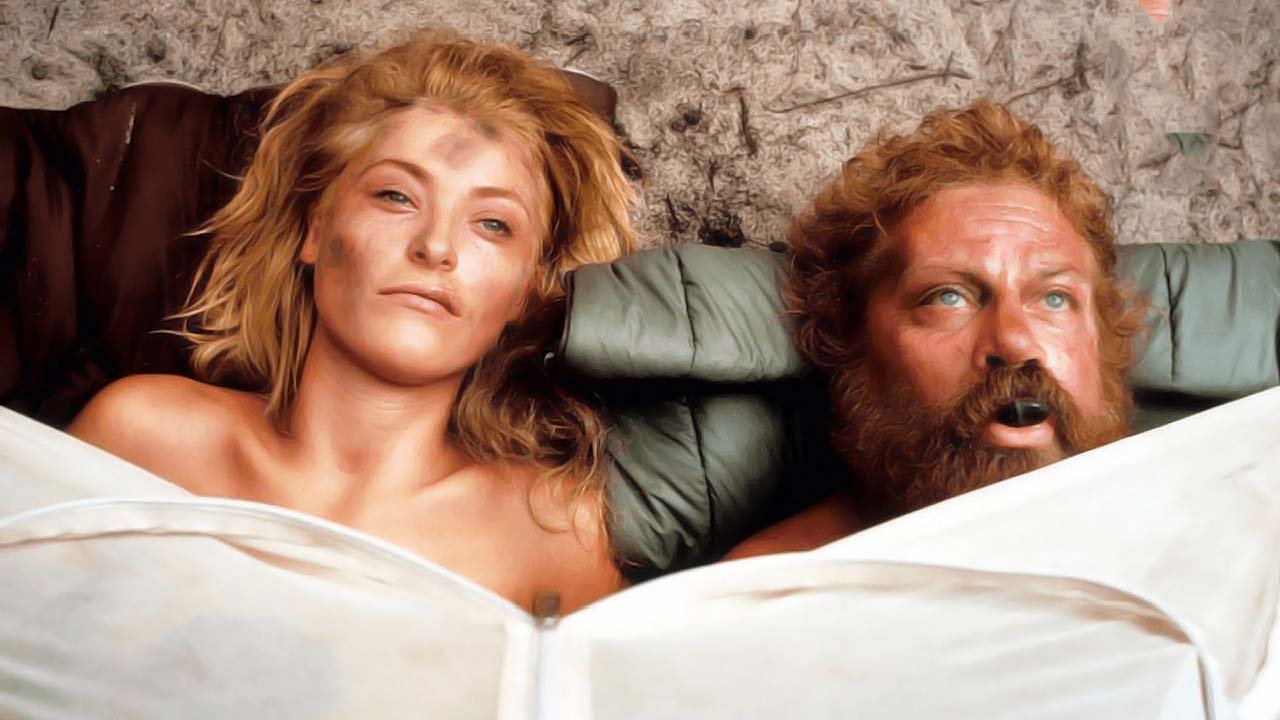

Based on Lucy Irvine's real-life memoir detailing her year on the island of Tuin with writer Gerald Kingsland, Castaway plunges us immediately into the uncomfortable arrangement between the middle-aged, somewhat boorish Gerald (Oliver Reed) and the much younger, idealistic Lucy (Amanda Donohoe). They are virtual strangers agreeing to shed civilization – and presumably, its constraints – for 365 days of isolated cohabitation. Roeg, ever the master dissector of time and psyche (think Don't Look Now (1973) or The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)), doesn't give us a straightforward survival narrative. Instead, he crafts a fragmented, almost dreamlike exploration of human behaviour stripped bare. The initial idyll of turquoise waters and swaying palms quickly dissolves, replaced by the mounting pressures of dependency, boredom, sexual tension, and the slow erosion of personalities under duress. What happens to 'man' and 'woman' when the societal roles they perform are suddenly irrelevant?

A Crucible for Two Souls

The film rests almost entirely on the shoulders of its two leads, and their performances are magnetic, difficult, and utterly compelling. Oliver Reed, an actor whose off-screen reputation for volatility often preceded him, is perfectly cast as Gerald. He brings a fascinating blend of world-weariness, predatory charm, and pathetic vulnerability to the role. You sense Roeg expertly harnessing Reed's own larger-than-life, sometimes dangerous energy; there are moments where Gerald’s frustrations feel startlingly real, blurring the line between performance and persona. It’s a performance that makes you deeply uncomfortable, yet you can't look away.

Opposite him, Amanda Donohoe, in what was a breakout role, is simply remarkable as Lucy. She navigates the transition from a naive young woman drawn by romantic notions of escape to a hardened survivor forced to confront uncomfortable truths about herself and her companion. The film was known, perhaps even notorious, in its day for its frank depiction of nudity, and Donohoe handles these scenes with a bravery that underscores Lucy's vulnerability and eventual assertion of self. It’s a demanding role, physically and emotionally, and she delivers a portrayal of resilience that feels earned. Reportedly, the shoot itself, filmed on location in the stunning but challenging Seychelles, was intense, with Roeg fostering an atmosphere that kept his actors slightly off-balance, mirroring the characters' own psychological fraying.

Beneath the Surface: Trivia and Truth

Knowing the film stems from Lucy Irvine’s actual experiences adds a powerful layer. While adaptations always take liberties, the core truth – two individuals testing the very limits of compatibility in extreme isolation – resonates. Irvine's 1983 book Castaway was a bestseller, capturing the public imagination. The film, however, received a mixed reception. Some critics found it exploitative, particularly in its focus on the nudity and the power dynamics, while others praised its unflinching honesty and Roeg's distinctive, non-linear style which here effectively mirrors the characters' fractured sense of time and reality. It’s certainly not a comfortable watch, but its power lies in that very discomfort. Interestingly, the real Gerald Kingsland published his own, less successful, account after Irvine’s book took off, offering a different perspective on their year together – a reminder that 'truth' in such situations is often multifaceted.

The Lingering Glare of Isolation

What Castaway captures so effectively is the psychological weight of isolation and forced intimacy. The lush, tropical paradise becomes a pressure cooker. The absence of external society doesn't lead to freedom, but rather intensifies their reliance on, and conflict with, each other. The vast ocean surrounding them paradoxically shrinks their world down to the small, often painful, space between them. Roeg uses the stunning natural beauty not just as a backdrop, but as an ironic counterpoint to the ugliness of human behaviour under strain. Does the fantasy of escaping it all ever truly satisfy, or do we inevitably carry our baggage – our flaws, desires, and societal conditioning – with us, even to the remotest corners of the earth? The film suggests the latter, quite powerfully.

Renting this on VHS back in the day, perhaps drawn by the promise of adventure or the familiar face of Oliver Reed, often meant stumbling into a far deeper and more challenging cinematic experience than anticipated. It wasn't The Blue Lagoon (1980); it was something thornier, more adult, asking questions that linger long after the credits roll.

Rating: 7/10

Castaway is undeniably a challenging film, marked by Nicolas Roeg's signature elliptical style and featuring two incredibly raw, committed performances. Its pacing can feel uneven, and the relentless focus on the pair's often unpleasant dynamic won't be for everyone – the criticisms of exploitation aren't entirely without merit depending on your lens. However, its unflinching look at human nature under pressure, the powerhouse acting from Oliver Reed and Amanda Donohoe, and its sheer audacity make it a significant and memorable piece of 80s filmmaking. It earns its 7 for its bravery, its unforgettable central pairing, and the haunting questions it forces us to confront about ourselves.