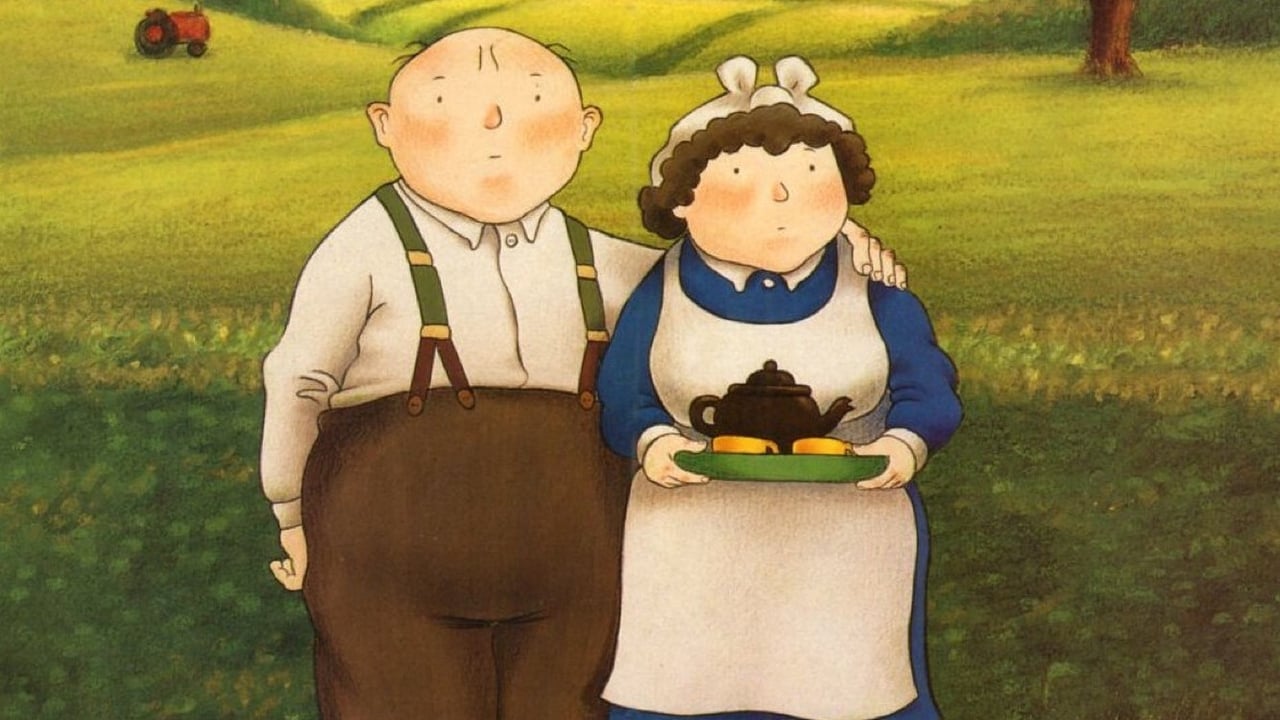

It arrives like a half-remembered lullaby tainted by an encroaching dread. When the Wind Blows (1986) isn't the sort of film you casually revisit, nor is it one easily forgotten once seen. Drawn from the deceptively gentle pages of Raymond Briggs' graphic novel of the same name, this animated feature stands as one of the most quietly harrowing cinematic experiences of the 1980s, a poignant testament to the ordinary lives caught beneath the shadow of extraordinary, unthinkable terror. Seeing that familiar Briggs art style, so closely associated with the festive warmth of The Snowman (1982), used to depict the slow, inexorable decline following a nuclear attack is a deliberate, devastating masterstroke.

An Everyday Apocalypse

The film introduces us to Jim and Hilda Bloggs, a retired couple living a simple, unassuming life in the English countryside. Voiced with heartbreaking authenticity by veteran British actors Sir John Mills (known for epics like Gandhi (1982) and Great Expectations (1946)) and Dame Peggy Ashcroft (an Oscar winner for A Passage to India (1984)), they embody a generation steeped in the 'keep calm and carry on' spirit of World War II. When news of impending nuclear war arrives, Jim, ever the diligent citizen, meticulously follows the instructions laid out in government pamphlets – the infamous "Protect and Survive" guides that were chillingly real artefacts of the era. He builds their "inner core or refuge" with doors, cushions, and misplaced optimism, while Hilda worries about the curtains and whether they have enough tea.

It's this mundane domesticity, rendered in traditional, hand-drawn animation against stark, often stop-motion backgrounds depicting their small cottage, that makes the unfolding tragedy so potent. Director Jimmy T. Murakami, who had previously worked on animation for films like Heavy Metal (1981), masterfully contrasts the Bloggs' gentle, almost childlike naivety with the grim reality they face. Their unwavering faith in official guidance, their inability to grasp the true nature of radiation sickness ("It's the fallout," Jim assures Hilda, "It'll blow over"), becomes almost unbearable to watch. Does their simple trust indict the authorities who offered such flimsy reassurances, or does it speak to a deeper human need to believe in order amidst chaos?

Voices in the Dust

The performances by Mills and Ashcroft are nothing short of astonishing. Recorded before the animation process began, their vocal interactions possess a natural rhythm and warmth that makes Jim and Hilda utterly believable. Ashcroft captures Hilda’s blend of gentle fussiness, pragmatism, and quiet affection perfectly. Mills, meanwhile, delivers Jim’s lines with a mixture of bluster, bewilderment, and poignant determination. Their dialogue, lifted largely from Briggs' original text, is filled with the small talk, gentle bickering, and shared memories of a long life together. It’s in these utterly ordinary exchanges, continuing even as their world literally dissolves around them, that the film finds its deepest emotional resonance. You don't just watch Jim and Hilda; you feel their confusion, their diminishing hope, their enduring love.

Interestingly, the film’s production itself mirrors its themes of human endeavour against daunting odds. The meticulous blend of animation styles was complex, and securing the soundtrack involved some heavy hitters. The title song, penned and performed by David Bowie, is hauntingly melancholic, while the score features contributions from Roger Waters of Pink Floyd fame, adding layers of atmospheric dread that perfectly complement the visuals. This wasn't just another cartoon; it was a serious artistic statement carrying significant weight, even reflected in its surprisingly lenient PG rating in the UK at the time – a decision that sparked considerable debate given the subject matter.

The Chill That Lingers

When the Wind Blows doesn’t rely on graphic horror. The true terror lies in the unseen – the radiation itself – and in the slow, painful erosion of normalcy. We witness the physical decline of Jim and Hilda, their growing sickness mirroring the decay of their surroundings. Their memories drift back to the Blitz, a time when hardship felt different, somehow manageable compared to this invisible, insidious enemy. There's a profound sadness in their inability to comprehend that this war offers no Anderson shelters, no 'all clear' signal, no chance to simply rebuild. This film serves as a stark counterpoint to the more action-oriented nuclear paranoia thrillers of the era, like WarGames (1983) or The Day After (1983), focusing instead on the quiet, personal cost paid by the most vulnerable.

Watching it again now, perhaps on a worn VHS tape pulled from the back of a shelf – I remember renting this from a local store, the cheerful cover art offering no warning – the film feels less like a period piece and more like a timeless cautionary tale. The specific anxieties of the Cold War may have shifted, but the questions it raises about blind faith, governmental responsibility, and the devastating human consequences of conflict remain terrifyingly relevant. It’s a film that doesn't flinch, forcing us to confront the fragility of the ordinary world we often take for granted.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score reflects the film's unique artistic achievement, its emotional power, and its unflinching commitment to its devastating theme. The brilliant voice work from Mills and Ashcroft, the innovative blend of animation, the haunting soundtrack, and Raymond Briggs' poignant source material combine to create an unforgettable experience. It loses a single point only because its unrelenting bleakness makes it an incredibly difficult film to endure, though that is precisely its intent and strength.

When the Wind Blows remains a profoundly moving and deeply unsettling piece of animation history – a quiet film that shouts its warning about the human cost of ignoring the gathering storm.