The puzzle box remains closed, yet the doorway feels permanently cracked open. Some visions, once glimpsed, refuse to fade, etching themselves onto the back of your eyelids. Clive Barker's original Hellraiser (1987) gave us intimate, domestic horror twisted into sadomasochistic nightmare fuel. But its sequel, Tony Randel's Hellbound: Hellraiser II (1988), flings the gates wide open, inviting us not just to peek, but to take a grand, terrifying tour of Leviathan's domain. It’s a descent into a colder, more expansive Hell, leaving behind the claustrophobia of one house for the infinite, chilling geometry of the Labyrinth itself.

Beyond the Walls of Reason

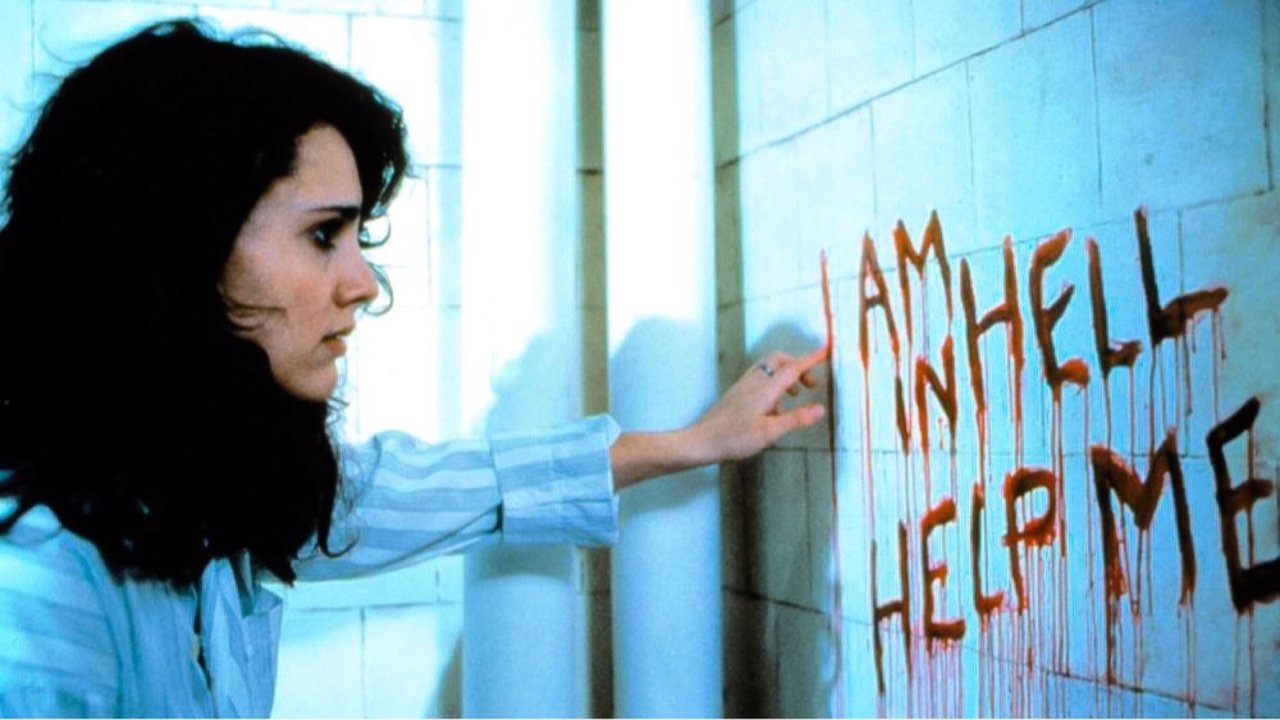

Picking up moments after the first film's bloody conclusion, Hellbound finds Kirsty Cotton (Ashley Laurence, embodying trauma with harrowing conviction) confined to the Channard Institute, a psychiatric hospital seemingly designed by Albert Speer channeling M.C. Escher. Her warnings about skinless uncles and extradimensional demons fall on deaf ears, particularly those of Dr. Philip Channard (Kenneth Cranham), the institute's director. Cranham plays Channard with a chilling blend of detached intellectual curiosity and burgeoning obsession that quickly curdles into outright malevolence. He’s not just studying the puzzle box; he’s seeking tenure in Hell. It's a performance that starts unsettling and escalates into something truly monstrous.

The catalyst for the film's plunge into the abyss is the resurrection of Julia Cotton (Clare Higgins, returning with even more vampish, regal menace). Remember that blood-soaked mattress Kirsty saw being hauled away? Channard retrieves it, providing a gruesome sacrifice (a patient driven mad by delusions of insects, poor soul) to reanimate Julia, this time skinless and ravenous. Higgins commands the screen, a queen regaining her horrific power, driven by an insatiable hunger and a desire to reunite with her Cenobite saviors. It was Higgins herself who suggested Julia should emerge wrapped in bandages, adding another layer of unsettling, mummy-like horror before her eventual, flesh-restored state.

A Grand Tour of Gehenna

Where the original film kept its horrors largely contained, Hellbound dares to visualize Hell itself. Scripted by Barker's longtime friend Peter Atkins (based on Barker’s story), the film transforms Hell from a mere concept into a tangible, albeit nightmarish, reality. The production design here is ambitious, crafting the Labyrinth as a vast, blue-toned maze of shifting perspectives and impossible architecture, presided over by the indifferent diamond god, Leviathan. It feels cold, desolate, and utterly alienating – a stark contrast to the fiery pits often imagined. This vision of Hell, vast and uncaring, feels uniquely disturbing, a bureaucratic nightmare realm where suffering is systematic, not chaotic.

The practical effects work, while occasionally showing its late-80s seams today, remains impressively visceral. Julia's resurrection, the various Cenobite designs (including some fleeting glimpses of fascinatingly grotesque new ones), and especially the climactic transformation of Dr. Channard are triumphs of physical artistry. Seeing these unfold on a grainy VHS tape, perhaps rented from a store with peeling posters in the window, had a particular power. The tangibility of the gore, the weight of the latex and makeup – it felt disturbingly real in a way that slicker, modern CGI often struggles to replicate.

Reportedly, the production was somewhat rushed, with Tony Randel stepping into the director's chair after Barker focused on producing and his own directorial effort with Nightbreed (1990). This occasionally shows in the narrative, which sometimes feels less cohesive than the original, favouring shocking imagery and expanded lore over tight plotting. Yet, this slightly disjointed, dreamlike quality arguably enhances the film's descent into madness. We aren't just watching Kirsty navigate Hell; we feel cast adrift in it alongside her.

The Doctor Will See You Now

Let's talk about the Channard Cenobite. If Pinhead (Doug Bradley, ever iconic, even with slightly less screen time here) is the cold pontiff of pain, Channard becomes its ultimate, gleeful devotee. His transformation, orchestrated by Julia as a twisted gift to Leviathan, is the stuff of nightmares. Cranham's maniacal cries of "And I am the doctor!" as tendrils writhe and surgical implements fuse with his being... it's unforgettable. This creature, arguably more terrifying than Pinhead in this instalment, embodies the film's core theme: the human capacity for cruelty often surpasses even that of demons. It’s a design that reportedly took hours to apply, pushing practical makeup effects to their limit for the era. Doesn't that monstrous design still feel unnerving, even after all these years?

Scars That Remain

Hellbound: Hellraiser II is a rare horror sequel that doesn't just rehash the original but dramatically expands its universe. It dives deeper into the mythology, offering glimpses into the origins of the Cenobites (including Pinhead's human past) and solidifying the visual language of Barker's infernal creation. While perhaps less narratively focused than its predecessor, its sheer ambition, chilling atmosphere, unforgettable villainy from Higgins and Cranham, and grotesque practical effects cemented its place as a fan favourite and a cornerstone of 80s horror cinema. It proved the Hellraiser universe had more suffering – and sights – to show us.

It wasn't trying to be the intimate psychodrama of the first film; it aimed for epic, mythic horror. I remember renting this from 'Video Village' back in the day, the stark, disturbing cover art practically buzzing on the shelf. The experience was less about jump scares and more about a pervasive sense of dread, a feeling that you were witnessing something truly transgressive and otherworldly. It delivered on the promise of seeing Hell, and it was a vision not easily forgotten.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's audacious expansion of the Hellraiser mythology, its truly memorable villain performances (Higgins and Cranham are phenomenal), and its iconic, nightmarish practical effects, particularly the Channard Cenobite. The atmosphere and vision of Hell are remarkable. It loses a couple of points for a slightly less cohesive narrative compared to the original and pacing that occasionally falters, likely owing to its production timeline. However, its strengths far outweigh its weaknesses.

Hellbound remains a fascinating, brutal, and visually stunning journey into the further regions of experience, a vital chapter in the saga that proved Hell had dimensions we hadn't even begun to imagine. We have such sights to show you, indeed.