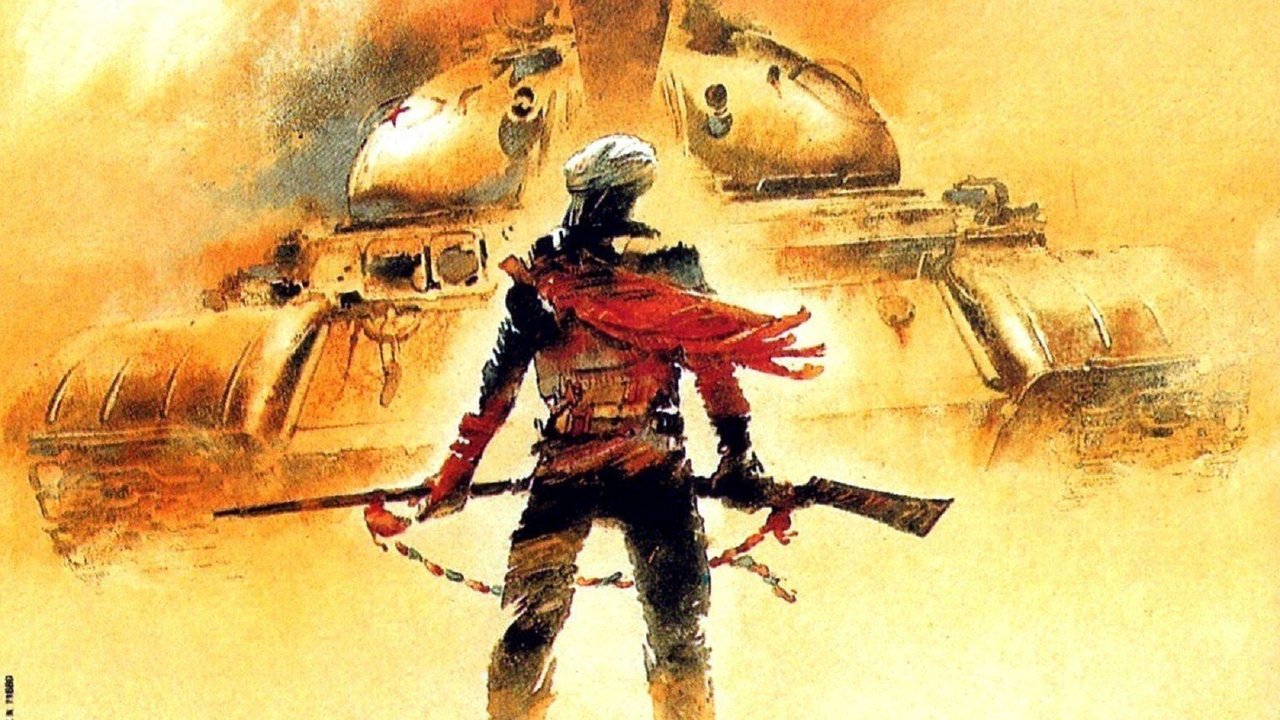

Dust hangs thick in the air, not just from the arid Afghan landscape, but from the moral ambiguities churned up by the hulking T-55 tank at the heart of The Beast of War (1988). This isn't your typical gung-ho 80s war flick; watching it back then, perhaps on a slightly fuzzy rental tape procured after scanning rows of more explosive box art, felt different. It was unsettling, a dispatch from a conflict – the Soviet-Afghan War – that was still a raw nerve in global politics. There’s a weight to this film, a kind of brutal honesty that burrows under your skin long after the VCR whirs to a stop.

Into the Crucible

Directed by Kevin Reynolds, who would later helm bigger, though arguably less impactful, adventures like Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991) and Waterworld (1995), The Beast of War throws us directly into the furnace. Following a savage raid on a Pashtun village, a Soviet tank crew finds themselves cut off, lost deep within enemy territory. Their commander, Daskal, portrayed with chilling conviction by George Dzundza, is a man forged by war's cruel logic, prioritizing the mission and the machine – the titular "Beast" – above all else, including the lives of his own men or the Afghan prisoners they take. The premise stems from a play by William Mastrosimone, who undertook the astonishing risk of travelling into Afghanistan during the conflict to gather material, lending the narrative an uncomfortable layer of authenticity.

Inside the Iron Coffin

Much of the film’s power derives from the suffocating intimacy within the tank's confines. Reynolds masterfully uses the cramped space to amplify the mounting tension and fraying nerves of the crew. We feel the heat, the grime, the constant jarring impacts. Daskal rules this small, metallic world with an iron fist, his paranoia and ruthlessness escalating as their situation worsens. Dzundza is magnetic, embodying a specific kind of military zealotry that’s terrifying because it feels utterly believable – a man convinced of his righteousness even as he commits atrocities. It’s a performance that avoids caricature, hinting at the pressures and past traumas that might have shaped such a man. Remember Dzundza from The Deer Hunter (1978)? He brings a similar grounded intensity here, but twisted into something much darker.

A Crisis of Conscience

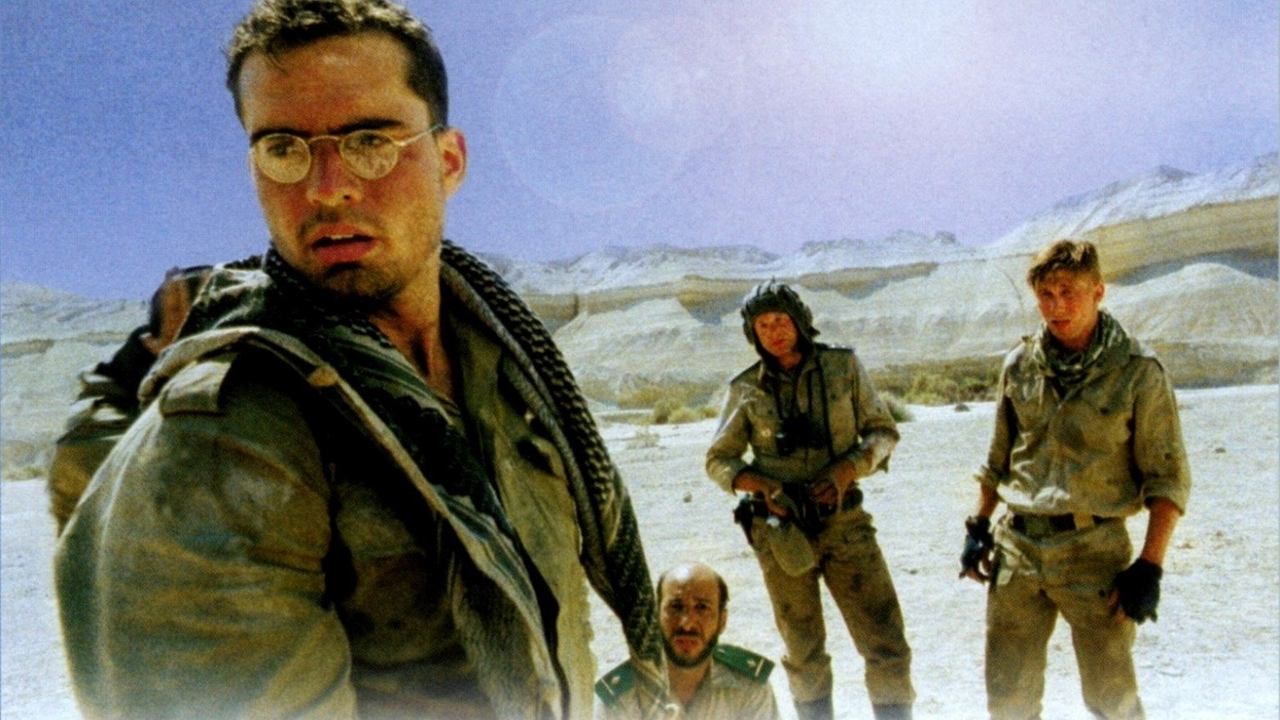

Standing in stark contrast is Koverchenko, the tank driver played by a young, intense Jason Patric. He becomes the film's conscience, increasingly disturbed by Daskal's brutality and the senselessness of their orders. Patric delivers a wonderfully understated performance, his disillusionment growing visibly in his eyes and posture. His struggle – loyalty to his comrades versus the dictates of his own morality – forms the film's ethical core. When Daskal orders an execution Koverchenko cannot stomach, the fracture becomes irreparable, setting the stage for a desperate shift in allegiance. Doesn't this internal battle feel timeless, echoing dilemmas faced in countless conflicts throughout history?

The Hunters Become the Hunted

The film doesn't solely focus on the Soviets. We also follow the pursuing Mujahideen, led by Taj (Steven Bauer, bringing fiery charisma years after Scarface). Their quest for vengeance is driven by personal loss and cultural imperative. The film introduces the Pashtun concept of Nanawatai – the sacred obligation to grant sanctuary, even to an enemy, if they formally request it. This adds a fascinating layer of cultural depth, turning the chase into something more than just tactical manoeuvres; it becomes a test of ancient codes against modern warfare's savagery. One striking choice Reynolds made was leaving much of the Russian dialogue unsubtitled, particularly early on. This decision forces the viewer, regardless of their background, to initially experience the Soviets as the Afghans might: an alien, imposing force speaking an incomprehensible tongue.

Retro Fun Facts: Grit Behind the Scenes

The making of The Beast of War was as challenging as its subject matter. Lensed in the deserts of Israel, the production utilized actual Soviet T-55 tanks (captured by Israel in previous conflicts), adding a visceral realism rarely seen. Imagine the logistics of maneuvering those behemoths in the heat! The film cost a respectable $20 million back in 1988 (around $52 million today), but sadly tanked at the box office, pulling in a mere $1.6 million ($4.2 million adjusted). It seemed audiences weren't quite ready for such a grim, morally complex take on a contemporary war. Yet, like so many underappreciated gems, it found a dedicated following on VHS and later DVD, becoming a cult classic revered for its unflinching portrayal of war's brutal realities. It’s a testament to how home video could give deserving films a second life. I distinctly remember the stark, imposing cover art on the rental shelf – it promised something intense, and it delivered.

An Unflinching Gaze

Cinematographer Douglas Milsome (who shot Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket the year prior) captures the harsh beauty and unforgiving nature of the landscape, making it as much a character as the humans or the machine. The action, when it comes, is desperate and ugly, devoid of heroic gloss. The tank itself feels genuinely menacing, an unstoppable force grinding across the plains, yet also vulnerable, a metal shell encasing fragile human lives. Reynolds directs with a steady, unsentimental hand, refusing easy answers or comfortable resolutions.

The Beast of War isn't an easy watch. It’s bleak, violent, and deeply unsettling. But it’s also a powerful, thought-provoking piece of filmmaking that tackles complex themes with intelligence and conviction. The performances are uniformly strong, anchored by Dzundza’s terrifying commander and Patric’s soulful dissident. It stands as one of the more unique and challenging war films to emerge from the 80s, a far cry from the flag-waving action spectacles that often dominated the genre during that decade.

Rating: 8.5/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional intensity, outstanding central performances, and its brave, unconventional approach to the war genre. It’s a gritty, morally complex film that avoids easy answers and stays with you. The justification lies in its powerful atmosphere, the compelling ethical struggles it portrays, and its enduring relevance as an anti-war statement disguised as a tense pursuit thriller. It might lack the polish of bigger studio pictures, but its raw impact is undeniable.

For those seeking more than just explosions from their 80s war movies, The Beast of War remains a vital, if harrowing, discovery from the back shelves of VHS Heaven. What truly lingers is the haunting image of that lone tank against the vast, indifferent desert – a potent symbol of destructive power utterly lost and ultimately consumed by the very land it sought to conquer.