Okay, settle in, maybe rewind your thoughts a bit. Remember that feeling when a movie didn't just entertain you, but fundamentally rewired how you thought about storytelling? For me, stumbling upon Memento (2000) felt exactly like that – a jolt to the system, arriving just as the flickering glow of the CRT was giving way to the sharper promise of DVD, yet carrying an intensity that felt both timeless and utterly new. It wasn't your typical Friday night rental; it was an invitation into a fractured mind, a puzzle box demanding your full attention.

Starting at the End

What grabs you immediately, and never lets go, is the sheer audacity of its structure. We meet Leonard Shelby, a man stripped of his ability to form new memories since a brutal attack that claimed his wife's life. His world exists only in Polaroid snapshots, hastily scribbled notes, and indelible tattoos – fragments he uses to piece together the identity of his wife's killer. Director Christopher Nolan, in only his second feature film (following the micro-budget Following (1998)), doesn't just tell this story; he plunges us headfirst into Leonard's condition. The narrative unfolds in two interwoven timelines: one moving forward in stark black and white, the other backward in colour, each colour scene ending precisely where the previous one began chronologically. It sounds complicated, and it is, but the effect isn't confusion for confusion's sake. It's empathy. We, like Leonard, are constantly playing catch-up, trying to make sense of situations already in progress, relying on the clues presented, never quite sure who or what to trust. It’s a brilliant gamble that pays off spectacularly, forcing us to experience the world through his perpetually resetting consciousness.

The Man Who Wasn't There

At the heart of this temporal maze is Guy Pearce. Fresh off his sharp turn in L.A. Confidential (1997), Pearce delivers a career-defining performance as Leonard. He embodies the character's tragedy not through histrionics, but through a chillingly vacant focus. There's a determination etched onto his face, fuelled by vengeance, yet beneath it lies a profound vulnerability, the constant, terrifying awareness that his reality could shift, that the 'facts' he relies on could be illusions. Pearce reportedly suggested shaving his head for the role, adding to that sense of stripped-down intensity. He makes Leonard's condition feel terrifyingly real – the frustration, the flicker of recognition that vanishes, the desperate reliance on his self-created system. It’s a performance built on absence, on the struggle to maintain identity when the very fabric of experience unravels every few minutes. It’s fascinating to know that Nolan sought Pearce out specifically after seeing L.A. Confidential, feeling he had the necessary gravitas and intelligence. Apparently, Brad Pitt had shown interest early on but scheduling conflicts intervened – a twist of fate that feels almost perfect in retrospect.

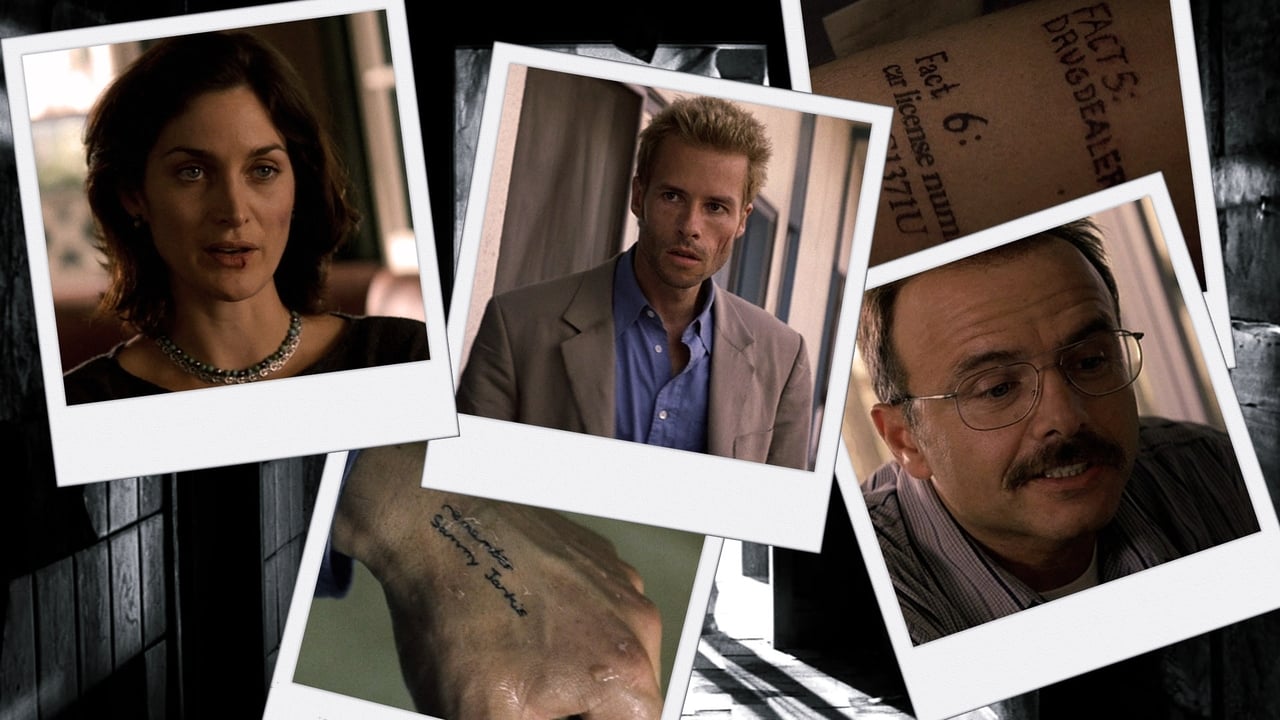

Faces in the Fog

Leonard isn't navigating this fragmented landscape alone, though 'help' is a dangerously relative term here. Carrie-Anne Moss, hot off the cultural phenomenon of The Matrix (1999), plays Natalie, the bartender whose motives shift like sand. Is she an ally, a victim, or a manipulator exploiting Leonard's condition? Moss plays her with a captivating ambiguity, a hardness masking potential pain, or perhaps just calculation. Then there’s Teddy, brought to life with unsettling affability by Joe Pantoliano (another Matrix alum, but let's not forget his memorable turns in classics like The Goonies (1985)). Teddy presents himself as a friend, maybe a cop, helping Leonard navigate the underworld. Pantoliano excels at playing characters you instinctively distrust, and Teddy is a masterclass in that slippery charm. Are they guiding Leonard, or are they merely characters in a narrative he’s constructing, perhaps incorrectly, for himself? The dynamic between these three, fraught with suspicion and dependency, forms the film's emotional core.

Crafting Chaos: Behind the Fragments

The film's brilliance feels even more potent when you consider its relatively modest origins. Based on a short story, "Memento Mori," penned by Nolan's own brother, Jonathan Nolan (who would later co-write The Dark Knight (2008) and create TV's Westworld), the project was a testament to focused vision. It was shot in a brisk 25 days on a budget often cited around $4.5 million – a figure that seems almost impossible given the film's complexity and polish (that's roughly $8 million in today's money, still lean for such a film). The distinct visual style – the cool, objective feel of the black-and-white sequences charting Leonard’s ‘present’ actions, contrasted with the richer, yet equally unreliable, colour of the backward-moving plotline – wasn’t just aesthetic; it was crucial narrative signposting. The editing, a monumental task handled by Dody Dorn (who rightfully earned an Oscar nomination), is the invisible engine driving the disorientation and eventual, devastating clarity. Filming primarily around the sun-bleached, anonymous sprawl of the San Fernando Valley lends the film a specific kind of neo-noir atmosphere, less rain-slicked streets, more existential dread under blinding sunlight.

The Echo of a Lost Memory

Memento wasn't just a critical darling upon release (garnering significant buzz at festivals like Sundance); it felt like a genuine cinematic event. It arrived at a time when filmmakers were increasingly playing with time and perception, but Nolan's structural ingenuity felt radical. Its influence can be seen in countless thrillers that followed, attempting similar narrative tricks, though rarely with such purpose or emotional resonance. For collectors among us, who remembers the clamour for that limited edition DVD? Released in a sleeve designed like Leonard's own file, complete with notes and 'evidence', it was a brilliant piece of meta-packaging that perfectly captured the film's tactile, clue-gathering essence – a fascinating artefact from the dawn of the format wars, bridging the gap from our beloved VHS tapes. The film grossed around $40 million worldwide (about $71 million today), a significant return on investment that firmly established Christopher Nolan as a major directorial talent to watch, paving the way for his later blockbusters like Inception (2010).

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score reflects Memento's audacious concept, flawless execution, and Guy Pearce's stunning central performance. Its innovative structure isn't merely a gimmick; it's integral to the film's themes of memory, identity, and the subjectivity of truth. The supporting cast is pitch-perfect, and Nolan's direction is confident and controlled, crafting a palpable sense of unease and intellectual engagement. It loses perhaps a single point only because its demanding nature might not appeal to absolutely everyone, but its impact and artistry are undeniable.

Memento lingers long after the credits roll, leaving you questioning not just Leonard's reality, but the reliability of your own memories and the narratives we construct to make sense of our lives. What truths do we choose to forget, and what fictions do we choose to live by? It’s a film that truly gets under your skin – much like one of Leonard's own tattooed reminders.