How often does a simple case of mistaken identity lead not to frantic slapstick, but to a quiet, almost philosophical meditation on fate and connection? It's a rare thing, especially in the landscape of 80s cinema, often drawn to louder, more explosive narratives. Yet, that's precisely the gentle magic conjured by David Mamet's 1988 film, Things Change. It arrived not with a bang, but with a wry smile and a knowing nod, a cinematic oddity that felt instantly unique on the video store shelf. I distinctly remember the understated VHS cover catching my eye amidst the usual action heroes and screaming teens – it promised something different, and it certainly delivered.

An Offer You Can Refuse... Or Can You?

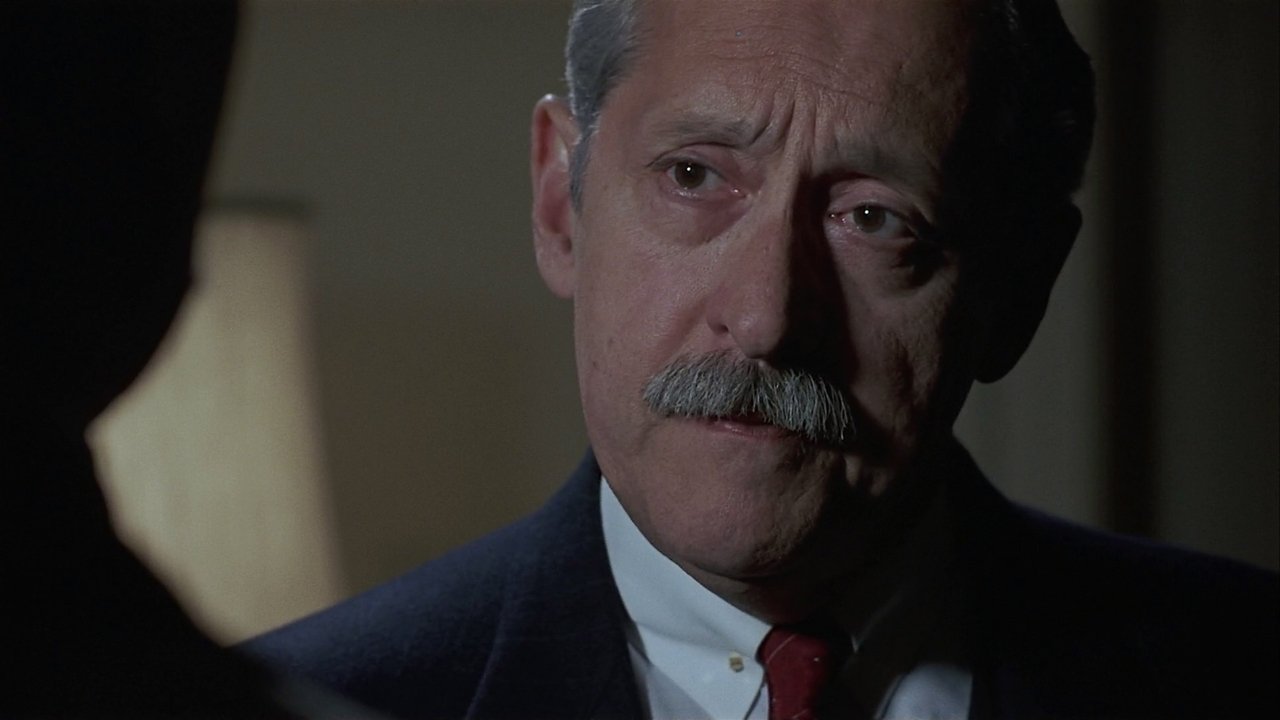

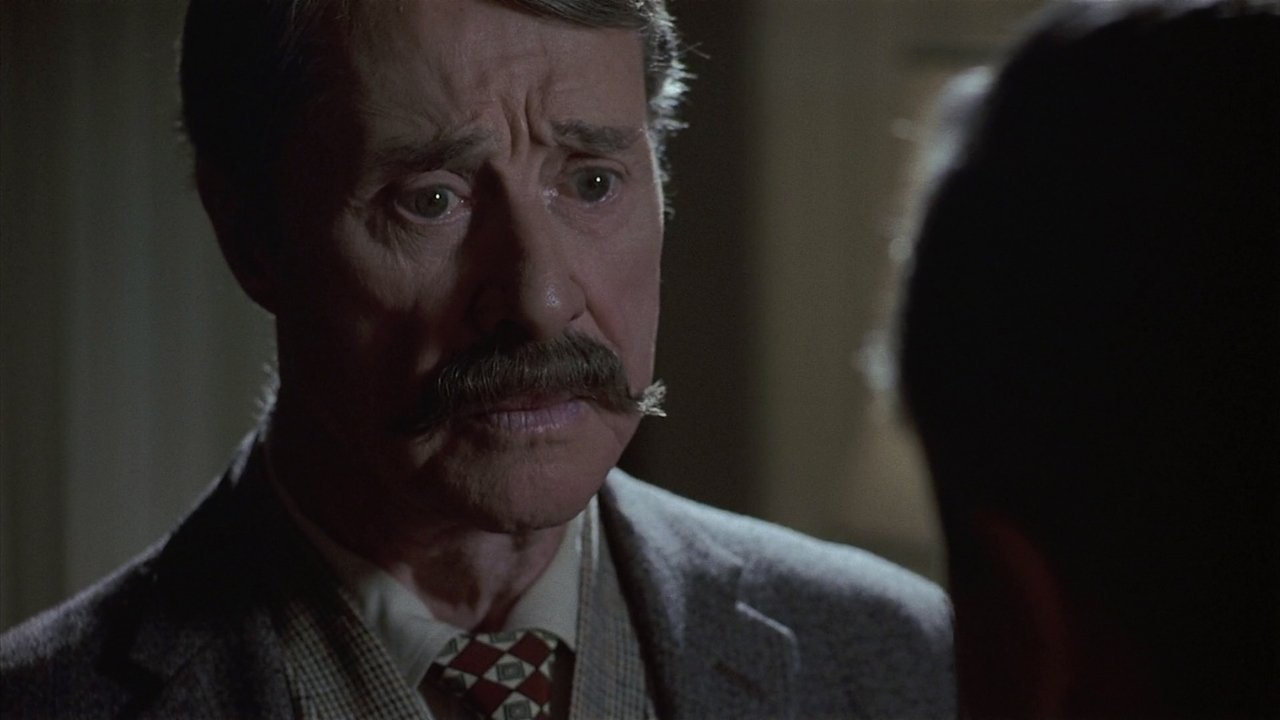

The setup is pure Mamet, filtered through an unexpectedly gentle lens. Gino (Don Ameche), an elderly, unassuming Italian shoeshiner in Chicago, bears a passing resemblance to a high-ranking Mafioso. When the real Don commits a murder, the local bosses, led by the pragmatic Mr. Green (Robert Prosky), make Gino an offer: confess to the crime, serve a few years, and upon release, receive his lifelong dream – a fishing boat on the sunny shores of Sicily. Gino, a man of simple dignity and perhaps weary resignation, agrees. Tasked with babysitting Gino over one last weekend before the confession is Joe Mantegna's Jerry, a low-level mob flunky desperate to get back in the bosses' good graces after a past blunder. His instructions are simple: keep Gino quiet, keep him happy, don't let him leave the hotel room.

Of course, things immediately deviate. Jerry, feeling pity and a strange sense of responsibility for the old man, decides Gino deserves one last blowout weekend. Against strict orders, he takes him to Lake Tahoe, intending a quiet trip. But Gino's quiet gravitas and resemblance to somebody important lead everyone they encounter – from hotel managers to rival mob bosses vacationing nearby – to assume he's a powerful Don. Jerry, caught in the escalating misunderstanding, finds himself playing along, introducing Gino as the formidable figure everyone imagines him to be.

The Stillness Between the Lines

What unfolds isn't a typical gangster farce, though moments of quiet absurdity certainly bubble up. Instead, Things Change becomes a fascinating character study, centered on the developing bond between the world-weary Gino and the perpetually anxious Jerry. Don Ameche, in a role that feels miles away from his energetic Oscar-winning turn in Cocoon (1985) just three years earlier, is simply magnificent. He imbues Gino with a profound stillness, a quiet acceptance of life's currents. His wisdom isn't proclaimed; it's observed in his silences, his simple gestures, his bemused reactions to the chaos swirling around him. It's a performance of subtle grace, utterly convincing and deeply moving. For their work here, both Ameche and Mantegna deservedly shared the Best Actor prize at the Venice Film Festival that year.

Joe Mantegna, a frequent collaborator with Mamet on stage and screen (audiences might remember him from Mamet's previous film, the twisty House of Games from 1987), is the perfect counterpoint. His Jerry is a bundle of nerves, ambition, and surprisingly, conscience. He’s a man trying so hard to be tough, to play the gangster game, but his fundamental decency keeps getting in the way. Watching him navigate the increasingly precarious situation in Tahoe, torn between his orders and his growing affection for Gino, is both funny and genuinely touching.

Mamet & Silverstein: An Unlikely Harmony

The screenplay, co-written by David Mamet and, remarkably, the beloved children's author, poet, and songwriter Shel Silverstein (Where the Sidewalk Ends, A Light in the Attic), is a marvel of understatement. One might wonder how the sharp, often cynical rhythm of Mamet's dialogue would blend with Silverstein's whimsical sensibility. Yet, the combination works beautifully. The dialogue retains Mamet's characteristic precision and clipped rhythm, but it's imbued with a warmth and gentle humour often absent in his more hard-boiled works. Reportedly, the two conceived the story together, with Mamet handling structure and dialogue while Silverstein focused on character nuances and humour – a collaboration that yielded a unique flavour. It’s less about plot mechanics and more about the spaces between words, the unspoken understandings, the small, ironic twists of fate. It asks us, gently, what truly defines a person – their reputation, their actions, or some quieter essence within?

The film itself carries Mamet's directorial stamp: clean compositions, an observant but unobtrusive camera, and a deliberate pacing that allows the characters and their interactions to breathe. It eschews flashy visuals or complex action, focusing instead on the actors and the subtle shifts in their relationships. This deliberate pace might have contributed to its modest performance at the box office (grossing around $8 million against its budget), especially compared to louder 80s comedies or gangster films. It wasn't designed for multiplex bombast; it felt more like a discovery, a hidden gem waiting on the VHS shelf for the discerning viewer.

A Quiet Corner of VHS Heaven

Things Change isn't a film that shouts its themes from the rooftops. It unfolds patiently, rewarding viewers who appreciate nuance, quiet observation, and masterful acting. It’s a film about how circumstances can alter perception, how unlikely friendships can blossom in the strangest of gardens, and how sometimes, simply accepting the absurdity of it all is the only way through. It explores obligation and choice, but with a philosophical shrug rather than heavy-handed moralizing. Doesn't the quiet dignity Ameche portrays feel like a rare commodity, both then and now?

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional performances, particularly from Ameche and Mantegna, its cleverly understated script, and its unique, gentle tone that sets it apart from typical genre fare. It earns its points through sheer charm, intelligence, and heart. While its deliberate pacing might not grab every viewer accustomed to faster narratives, its subtle rewards are significant. It's a film that doesn't just entertain; it lingers, leaving you with a thoughtful smile and a quiet appreciation for life's unexpected detours.