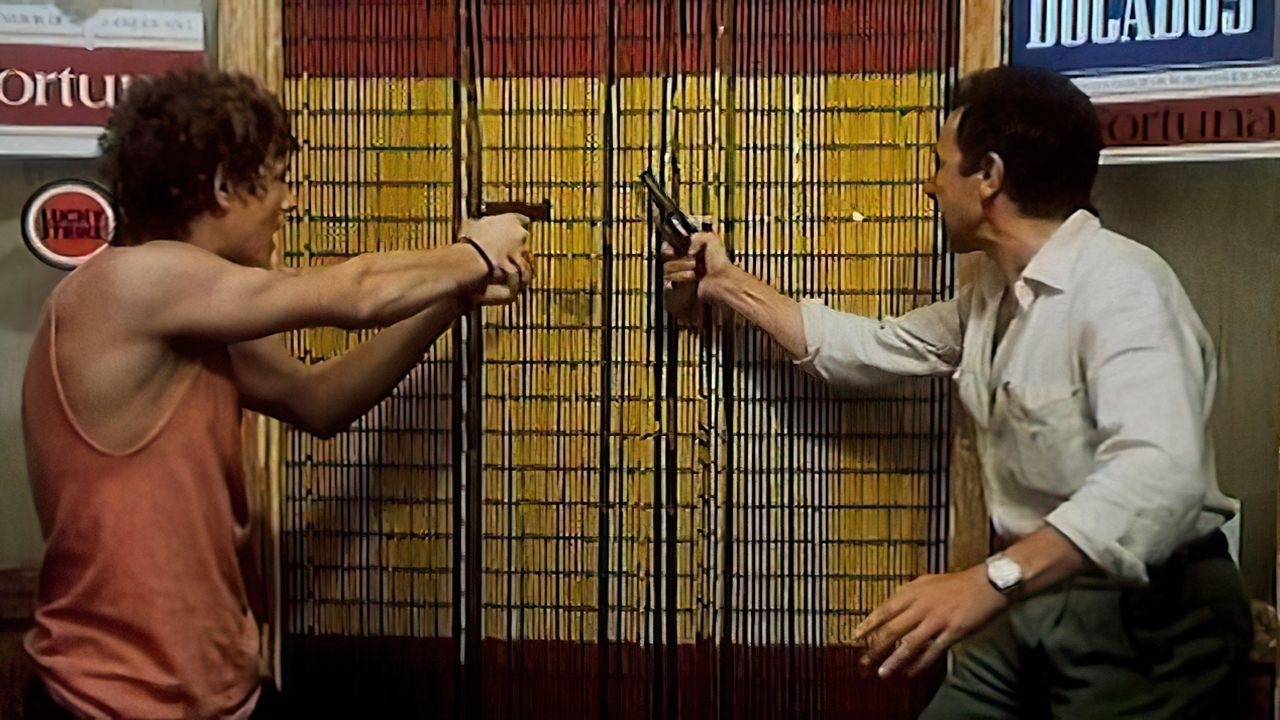

It begins, as these things often do, with desperation. Not the operatic kind, but the grinding, everyday sort that festers in the overlooked corners of a city. In El estanquero de Vallecas (The Tobacconist of Vallecas, 1987), that corner is a humble tobacconist shop in Madrid's working-class neighborhood of Vallecas, and the desperation belongs to Leandro and Tocho, two young men whose attempt at an armed robbery goes spectacularly wrong, trapping them inside with the formidable owner, Doña Justa, and her niece. What unfolds isn't just a hostage drama; it's a microcosm of Spanish society in the midst of transition, viewed through the unflinching lens of director Eloy de la Iglesia.

Trapped Between Walls and Worlds

From the outset, the film establishes a palpable sense of place. This isn't a stylized Hollywood heist; it's sweaty, clumsy, and painfully real. The estanco itself becomes a character – small, cluttered, a space where lives intersect daily, now transformed into a pressure cooker. De la Iglesia, a master of Spanish social realism often associated with the raw cine quinqui genre (films focusing on juvenile delinquency), uses this confined setting brilliantly. The tension isn't just about the guns; it's about the clash of worlds: the streetwise but ultimately naive robbers, the stern but pragmatic tobacconist, and eventually, the weary police negotiator trying to manage the situation from outside.

The initial moments are fraught with the expected fear and confusion. But as the hours wear on, something shifts. The film, adapted from a play by Alonso de Santos, excels in capturing the strange intimacy that can develop under duress. Boundaries blur. Conversations happen. Small kindnesses are exchanged alongside threats. It’s this human element, this refusal to paint characters in broad strokes, that elevates The Tobacconist of Vallecas beyond a simple genre piece.

Faces of Resilience and Despair

The performances are central to the film's power. Emma Penella is magnificent as Doña Justa. She’s no wilting victim; she’s tough, resourceful, and possesses a deep-seated understanding of the neighborhood and its struggles. Her interactions with the robbers, particularly Leandro, evolve from fear to a kind of pragmatic maternalism. She sees the desperation driving them, even as she condemns their actions. It’s a performance rooted in lived experience, utterly believable.

Then there’s José Luis Manzano as Leandro. A tragic icon of cine quinqui discovered by Eloy de la Iglesia, Manzano brought an almost painful authenticity to his roles, often playing characters mirroring his own struggles with poverty and addiction off-screen. His Leandro is jumpy, volatile, yet possesses a core vulnerability that Doña Justa senses. Watching him, knowing his real-life story (he sadly died young in 1992), adds an unavoidable layer of poignancy. His chemistry with Penella forms the emotional heart of the film. José Luis Gómez, as the police inspector Crespo, provides the weary voice of authority, caught between protocol and a grudging understanding of the societal factors at play.

A Director's Unflinching Gaze

Eloy de la Iglesia was never one to shy away from difficult subjects. His filmography is filled with explorations of the underbelly of Spanish society – drugs, poverty, marginalized communities – often made during and after the Franco dictatorship, pushing boundaries and challenging norms. The Tobacconist of Vallecas fits perfectly within this framework. While less explicitly confrontational than some of his other works (like El Pico), it subtly critiques the social inequalities and lack of opportunities that breed desperation like Leandro's. The film doesn't offer easy answers or moral judgments; it simply presents the situation with a raw, observational honesty.

Interestingly, despite the inherent tension, De la Iglesia allows moments of dark, almost absurd humor to surface. It's the humor of recognition, of shared humanity even in the worst circumstances. This blend prevents the film from becoming relentlessly grim, adding another layer of realism – life, even in crisis, is rarely just one thing.

Retro Fun Facts: Beyond the Counter

- From Stage to Screen: The film retains the tight focus of its theatrical origins (Alonso de Santos' play), benefiting from the claustrophobic intensity but expanded slightly by De la Iglesia to incorporate the bustling street life outside.

- The Quinqui Connection: José Luis Manzano was the face of cine quinqui. His casting wasn't just finding an actor; it was tapping into a specific cultural moment and a life that tragically reflected the themes of marginalization the genre explored. His collaboration with De la Iglesia produced some of the defining films of that movement.

- Vallecas as Character: Shooting on location in the actual Vallecas neighborhood lends an undeniable authenticity. You feel the grit, the energy, the specific identity of this working-class enclave, making it more than just a backdrop.

- A Different Kind of Tension: While released in 1987, when slicker action films were gaining traction, The Tobacconist feels deliberately unpolished. Its power lies in character interaction and social commentary, not pyrotechnics – a hallmark of De la Iglesia’s approach.

The Lingering Echo

What stays with you after watching The Tobacconist of Vallecas? It's the faces, primarily. The stoic resilience of Emma Penella, the haunted eyes of José Luis Manzano. It’s the uncomfortable questions it raises about societal structures and the paths people are forced onto. It's a film that uses a hostage crisis not just for thrills, but as a lens to examine class, desperation, and the surprising ways human connection can manifest. Does the frustration and lack of opportunity depicted feel distant, or does it still resonate in corners of our cities today?

It might lack the explosive action or high-concept premise that dominated many VHS shelves back in the day, but its raw humanity and sharp social observation give it a lasting power. It’s a potent reminder of a specific era in Spanish cinema and a testament to Eloy de la Iglesia's unique voice.

Rating: 8/10

Justification: The film achieves exactly what it sets out to do, delivering a powerful, character-driven drama disguised as a hostage thriller. Stellar performances, particularly from Penella and Manzano, anchor the piece in raw authenticity. De la Iglesia's direction is assured, capturing the claustrophobia and social undertones effectively. While perhaps niche for some viewers expecting straightforward genre fare, its depth and realism make it a standout example of 80s Spanish cinema.

Final Thought: A film that reminds us that behind every desperate act, there's often a complex human story waiting to be understood, even if only within the four walls of a neighborhood tobacconist shop.