There's a particular kind of disorientation that only certain films can induce, a feeling less like watching a story unfold and more like dreaming someone else's unsettling fever dream. Flickering onto the CRT screen from a well-worn VHS tape, Barry Shils' Motorama (1991) is precisely that kind of experience – a cinematic oddity that burrows under your skin and lingers long after the static hiss of the tape rewinding. It feels cut from the same strange cloth as After Hours (1985), and perhaps that's no coincidence, as both sprung from the singular mind of screenwriter Joseph Minion. Minion, it turns out, penned Motorama before his Scorsese collaboration, but it took years for this peculiar vision to find its way to the screen, landing like a strange artifact from a parallel, slightly hostile dimension.

A Different Kind of Road Trip

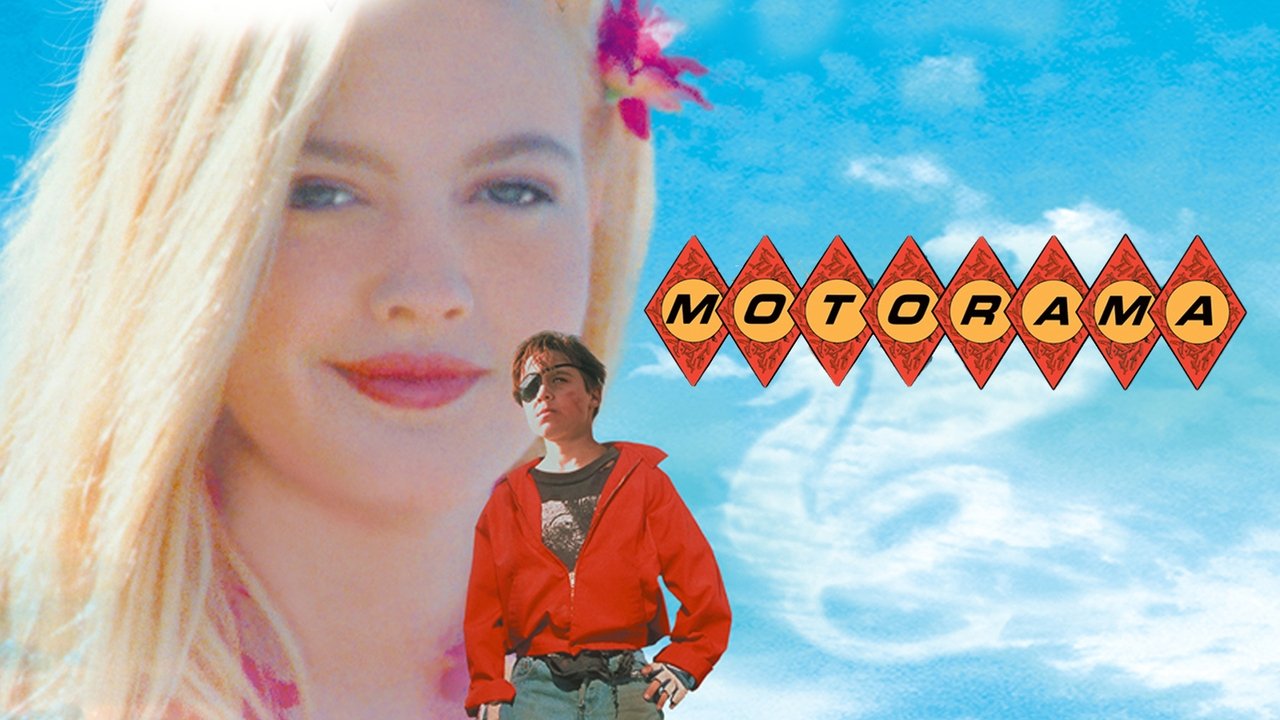

Forget the sun-drenched optimism often associated with the genre; Motorama presents a road trip through a fractured American landscape populated by the indifferent, the predatory, and the just plain weird. Our guide is ten-year-old Gus (a remarkably committed Jordan Christopher Michael), who flees his abusive home in a stolen Ford Mustang, embarking on a quest to collect state-specific game cards for the titular "Motorama" sweepstakes, chasing a $500 million grand prize. This isn't the wholesome adventure of a kid finding himself; it's a grimly satirical odyssey through states with names like South Lydon and Bergen, each stop offering potential progress towards his goal but simultaneously chipping away at... well, whatever innocence Gus might have possessed.

Welcome to Nowhere, USA

The world Shils and Minion create is one of the film's most potent elements. It’s recognizably American – dusty highways, greasy spoons, lonely gas stations – yet subtly skewed. The colors feel muted, the landscapes vast and empty, and the interactions Gus has are almost universally transactional or hostile. There's a pervasive sense of decay, not just physical, but moral. This isn't a celebration of the open road; it's a bleak commentary on the hollowness of the American Dream, where the pursuit of wealth (symbolized by the elusive game cards) leads only to exploitation and disillusionment. I remember renting this from the 'Independent' shelf at Blockbuster, sandwiched between perhaps Repo Man (1984) and Eraserhead (1977), and feeling that same sense of bewilderment mixed with fascination. You knew you were watching something different. Shot primarily across the stark landscapes of Utah and Nevada, the film uses these locations not for picturesque beauty, but to emphasize Gus's isolation and the sheer indifference of the world he navigates.

The Littlest Hardcase

At the center of this desolate landscape is Gus, played with unnerving intensity by Jordan Christopher Michael. Gus is no wide-eyed innocent. He's foul-mouthed, cynical, resourceful, and surprisingly tough, chain-smoking and driving with a grim determination that belies his age. Michael's performance is key; he never plays Gus for laughs or easy sympathy. He embodies the premature hardening required to survive this world, making choices that are often morally ambiguous, driven solely by the desperate logic of the game. It’s a complex, challenging portrayal, forcing us to question how much of his harshness is innate and how much is forged by the cruelty he encounters. What does it say about the journey when the destination seems predicated on losing oneself entirely?

Cameos in the Wasteland

Part of the strange charm, especially watching it now, is the gallery of familiar faces popping up in brief, often bizarre cameos. It feels like a roll call of cult cinema royalty and surprising appearances. There's former MTV VJ Martha Quinn as a sympathetic but ultimately unhelpful gas station attendant, the inimitable Michael J. Pollard (known from Bonnie and Clyde (1967)), Meat Loaf, Flea of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Mary Woronov (Eating Raoul, 1982), Allyce Beasley (Moonlighting), and even blink-and-you'll-miss-them appearances by Drew Barrymore and Lynchian regulars Jack Nance and Dick Miller. These appearances don't necessarily advance the plot in major ways, but they add layers to the film's surreal texture, reinforcing the feeling of a world populated by eccentric, often untrustworthy figures existing just on the periphery of Gus's relentless quest. It’s like flipping through strange TV channels late at night, catching glimpses of known personalities in unexpected, unsettling contexts.

Scratching Beneath the Surface

Motorama isn't an easy film to love. Its pacing can feel episodic, its tone relentlessly bleak, and its central character deliberately abrasive. Yet, there's an undeniable power to its singular vision. Minion's script skewers consumer culture and the desperate pursuit of escape velocity through wealth with a surgeon's precision, even if the anesthesia is decidedly lacking. Shils directs with a detached, almost clinical eye, allowing the inherent strangeness of the premise and the landscape to speak for itself. It avoids easy answers or catharsis, leaving the viewer pondering the nature of hope in a seemingly hopeless world. Does Gus’s relentless drive represent admirable resilience, or a tragic indoctrination into a broken system? The film offers no simple verdict. It didn't set the box office alight upon its limited 1992 release after debuting at festivals the year prior, but like many unique visions, it found its audience on home video – those late-night renters looking for something beyond the mainstream.

***

Rating: 7/10

Motorama earns this score for its sheer audacity, its unforgettable atmosphere, and Jordan Christopher Michael's startling central performance. It’s a truly unique piece of early 90s independent filmmaking, crafting a surreal and satirical road narrative that sticks with you. While its unrelenting bleakness and episodic nature might deter some, its commitment to its strange vision and its parade of oddball cameos make it a cult classic worth seeking out for adventurous viewers. It’s not comfort food cinema; it’s a potent shot of something far stranger, a forgotten map to a place both familiar and unnervingly alien.

What lingers most isn't the plot, but the feeling – the dust, the desperation, and the unsettling image of a child navigating an adult world stripped bare of its illusions.