There's a heat that radiates off the screen in Jamon Jamon, a palpable sense of sun-baked earth, simmering passions, and something almost mythic playing out under the stark Spanish sky. It's a film that arrived on our shores in 1992, often tucked away in the 'Foreign Films' section of the rental store, feeling both utterly alien and strangely familiar in its exploration of lust, class, and yes, cured ham. For many of us browsing those aisles, picking up a tape like this, directed by the provocative Bigas Luna, felt like uncovering a secret – something bolder, stranger, and more potent than the usual Hollywood fare.

Sun, Sex, and Serrano

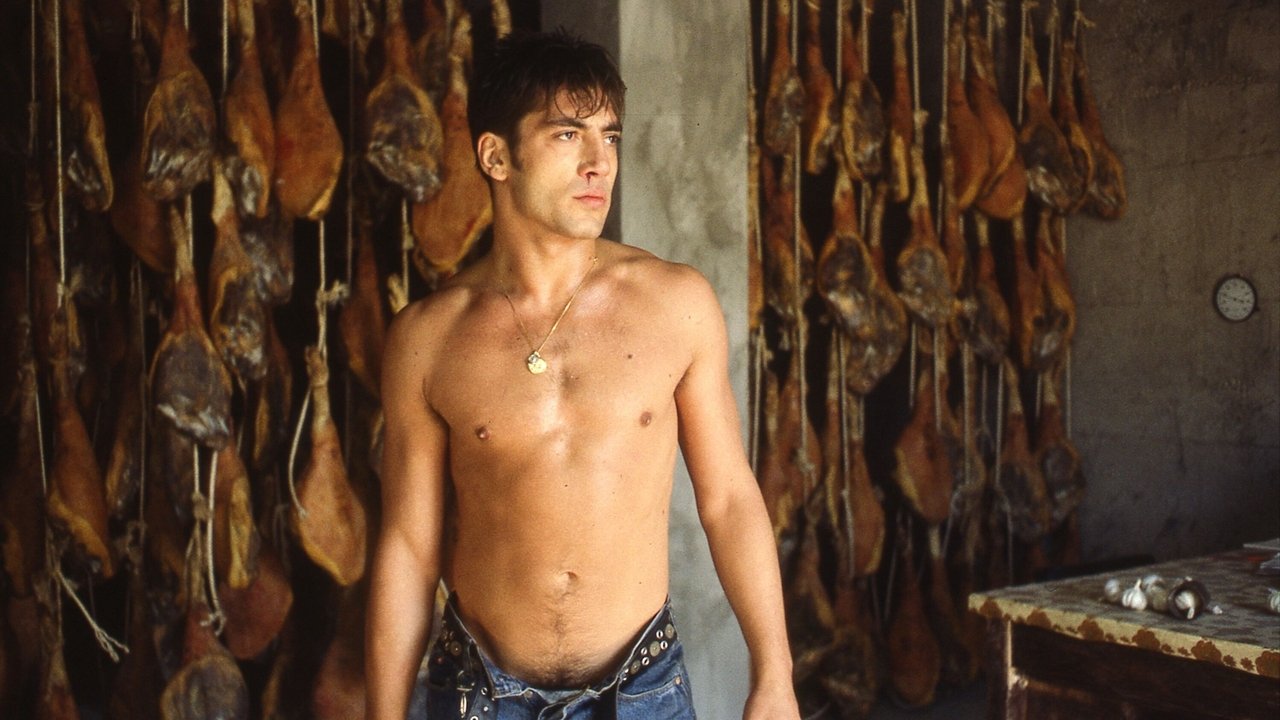

The setup is deceptively simple, bordering on fable. In a desolate town dominated by a giant roadside silhouette of an Osborne bull (a real Spanish icon, instantly grounding the film in cultural commentary), young Silvia (Penélope Cruz, in a stunningly raw film debut) works at a roadside underwear factory. She becomes pregnant by José Luis (Jordi Mollà), the scion of the wealthy family that owns the factory. His parents, particularly his domineering mother Conchita (Stefania Sandrelli, radiating manipulative sensuality), strongly disapprove of the match. Conchita’s bizarre solution? Hire the aspiring bullfighter and local stud, Raúl (Javier Bardem, in the role that announced his ferocious talent to the world), to seduce Silvia away from her son. What could possibly go wrong?

What unfolds is a uniquely Spanish blend of melodrama, dark comedy, and primal urges, all baked under the relentless Aragonese sun. Luna crafts an atmosphere thick with desire and dust. It’s less a conventional narrative and more a series of potent, often absurd, symbolic encounters. The film is deeply, unapologetically rooted in its location and culture – the obsession with ham (jamón) becomes a symbol for masculinity, virility, tradition, and even a weapon. It’s a choice so audacious it borders on parody, yet Luna and his actors commit entirely, lending the film its strange power.

Birth of Stars Under a Spanish Sky

The performances are key to Jamon Jamon's enduring fascination. Seeing Penélope Cruz here, so young (just 17 when filming began) and already possessing such natural screen presence and earthy sensuality, is remarkable. She embodies Silvia's mix of vulnerability and burgeoning strength. Opposite her, Javier Bardem is a force of nature as Raúl. He’s all swaggering machismo and brooding intensity, modelling underwear one minute and dreaming of the bullring the next. It’s a star-making turn, brimming with the raw charisma that would define his career. Interestingly, this marked one of the first times future husband-and-wife Cruz and Bardem shared the screen, and their chemistry, even in this tangled scenario, is undeniable. Jordi Mollà, often caught between these two magnetic poles, effectively portrays José Luis's weakness and frustration, trapped by maternal influence and his own desires.

Luna's Provocative Palette

Bigas Luna, who sadly left us too soon, had a background in painting and design before turning to film, and it shows. Jamon Jamon (the first of his "Iberian Portraits" trilogy) is visually striking, filled with unforgettable, sometimes shocking images: raw eggs consumed greedily, garlic cloves signifying potency (or lack thereof), the almost surreal final confrontation. Luna wasn't afraid to push boundaries, exploring sexuality with a frankness that felt bracing in the early 90s. He layers the film with symbolism – perhaps too overtly for some tastes – but it creates a heightened reality, a modern fable playing out with ancient, elemental passions. The film garnered significant attention internationally, winning the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival, signalling that Spanish cinema was offering something distinct and fiery.

Of Ham Duels and Hidden Depths

(Mild Spoiler Alert for the film's climax!)

The film’s most infamous scene, a climactic duel fought not with swords, but with hefty legs of cured ham, perfectly encapsulates its bizarre genius. It’s ridiculous, violent, strangely beautiful, and utterly unforgettable – Bardem, drawing on Spain’s bullfighting iconography (a world his own family had connections to), makes the confrontation feel both absurd and deadly serious. This wasn't just random weirdness; Luna was deliberately crafting archetypes – the lustful mother, the weak son, the virile interloper, the desired maiden – and setting them loose in a landscape charged with symbolism. It’s a commentary on class, machismo, and the inescapable power of desire, all served up with a side of dark, Iberian humour. The film’s budget was modest, but its impact, particularly in launching its young stars, was immense.

Legacy of a Savory Strangeness

Does Jamon Jamon hold up? Absolutely, though perhaps not as a conventional drama. It’s best appreciated as a bold, surreal, and sensual cinematic statement. It’s a film that gets under your skin with its unique atmosphere, its potent performances, and its sheer, unadulterated audacity. It explores timeless themes – the destructive power of jealousy, the complexities of class, the absurdity that often accompanies intense passion – in a way that feels utterly specific to Luna’s vision and its Spanish setting. Watching it again now, decades after first sliding that distinctive VHS tape into the machine, it still feels potent, provocative, and strangely delicious.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's undeniable artistic boldness, its career-launching performances, and its creation of a truly unique and unforgettable atmosphere. It’s not subtle, and its heavy symbolism might alienate some, but its raw energy and provocative vision make it a standout piece of early 90s European cinema. It’s a film that reminds you how exciting discovering something truly different in the video store could be.

Jamon Jamon remains a potent reminder of a time when filmmakers dared to be strange, sensual, and symbolic, leaving images seared into your memory long after the credits roll – much like the lingering taste of good Serrano ham.