There’s a certain kind of quiet that settles after violence, a stillness that feels heavier, somehow more profound than the silence that came before. It's this precise quality that permeates Takeshi Kitano’s 1997 masterpiece, Hana-bi (released simply as Fireworks in some territories), a film that arrived like a muted explosion on the international scene. Watching it again, decades after first encountering its stark beauty on a rented tape, that feeling returns – the unsettling calm nestled beside moments of shocking brutality. It doesn't just depict events; it forces you to sit with the emotional aftermath.

### Echoes in the Silence

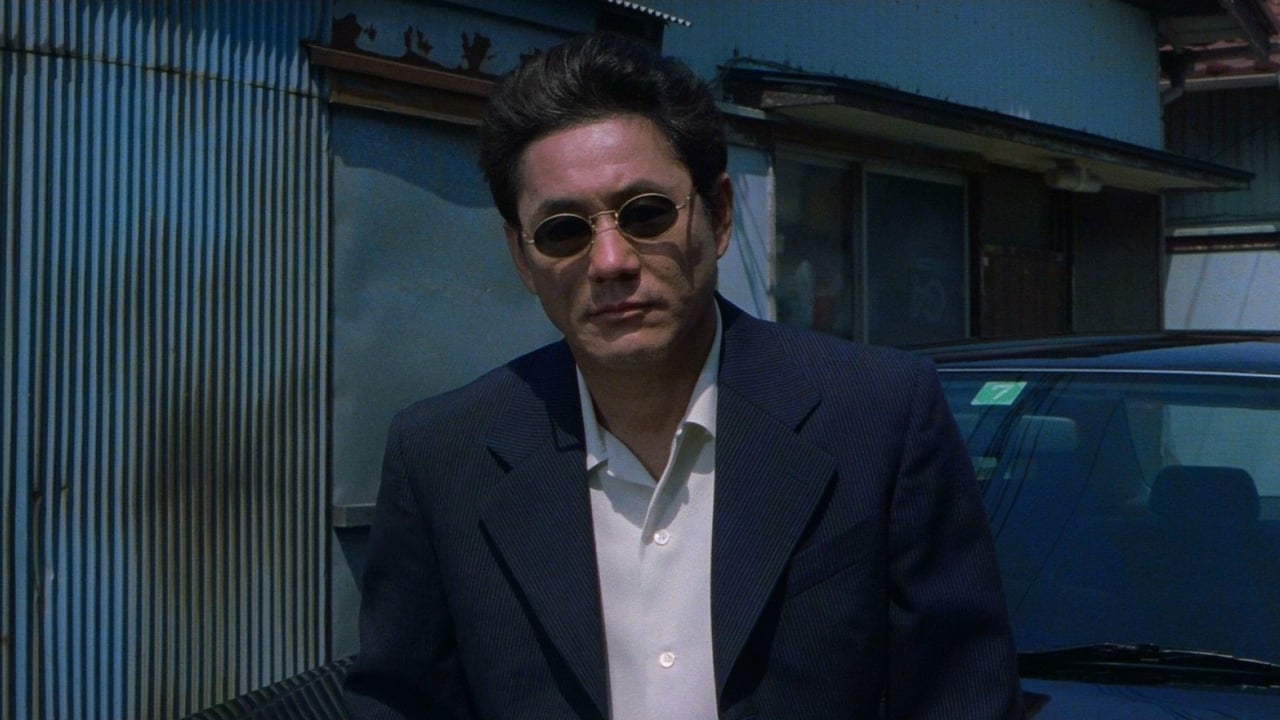

The film centers on Nishi (Takeshi Kitano himself), a detective whose world unravels with grim finality. A botched stakeout leaves his partner, Horibe (Ren Osugi), paralyzed and suicidal, while another colleague dies. Simultaneously, Nishi’s wife, Miyuki (Kayoko Kishimoto), faces a terminal illness. Burdened by guilt and grief, Nishi quits the force, borrows money from the Yakuza – a decision laden with inevitable consequence – and dedicates himself to caring for Miyuki and supporting Horibe. What follows is less a conventional crime narrative and more a poetic meditation on duty, love, and the stark choices made when facing the end. The atmosphere is thick with unspoken sorrow, punctuated by Nishi's often-wordless presence, a man seemingly numbed yet capable of devastating action.

### The Artist Behind the Badge

It’s impossible to discuss Hana-bi without acknowledging Kitano's multifaceted role. As writer, director, editor, and star, his signature is indelibly stamped on every frame. His performance as Nishi is a masterclass in minimalism; beneath the impassive exterior and occasional deadpan gag lies a volcano of suppressed emotion, erupting not in dialogue, but in sudden, decisive acts – often violent, sometimes unexpectedly tender. This wasn't just acting; it felt like watching a man confront his own demons on screen.

Indeed, the film carries the heavy weight of Kitano's own experience. He made Hana-bi following a near-fatal motorcycle accident in 1994 that left him partially paralyzed and required extensive surgery. His recovery period saw him take up painting, and these vibrant, often surreal works are poignantly integrated into the film through the character of Horibe, who takes up art after his paralysis. It's a deeply personal touch, weaving autobiography into the fabric of the narrative, transforming pain into a strange, complex beauty. This backstory isn't just trivia; it unlocks a deeper understanding of the film's preoccupation with life's fragility and the unexpected ways people find expression in the face of despair.

### Flowers and Fire

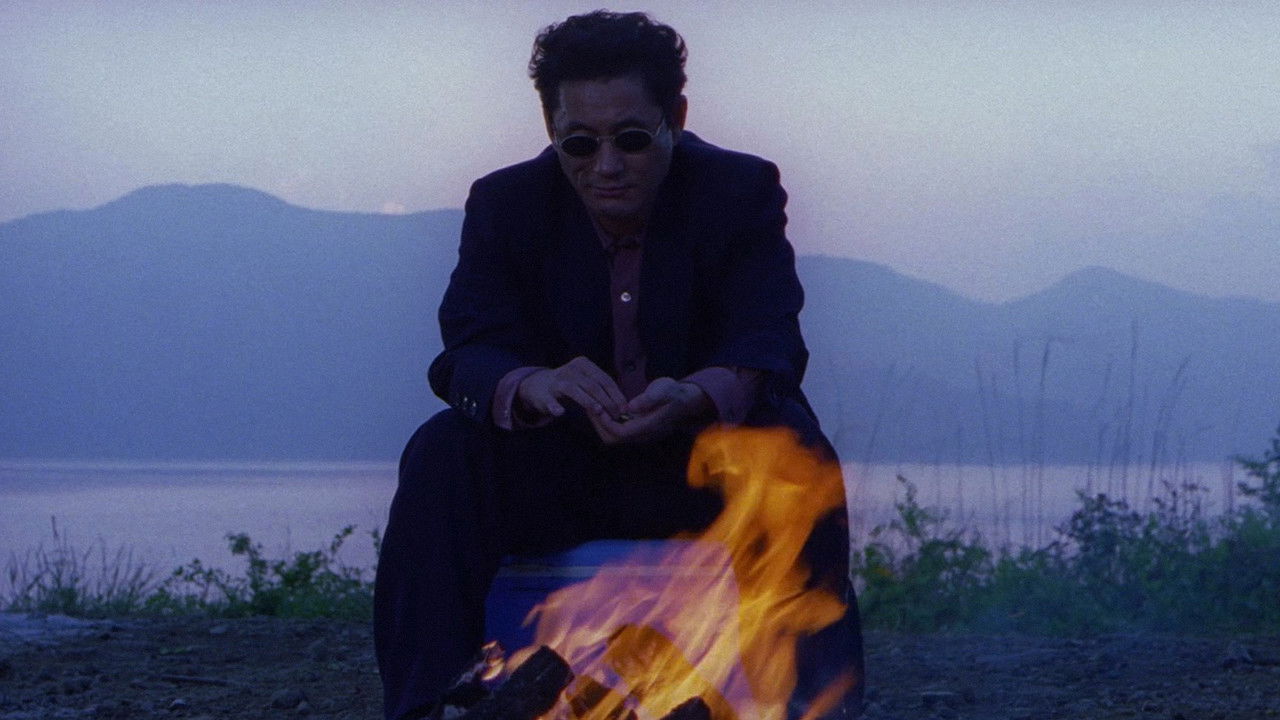

The Japanese title, Hana-bi, literally means "Fireworks," but the characters used – 花 (Hana: Flower) and 火 (Bi: Fire) – encapsulate the film's central duality: the delicate beauty of life juxtaposed with its potential for sudden, violent destruction. Kitano masterfully balances these extremes. Long, contemplative scenes of Nishi and Miyuki on their final journey together – sharing simple moments, playing games on the beach, observing the world with a quiet intensity – create a profound sense of intimacy. These moments are often wordless, relying on Kayoko Kishimoto's incredibly expressive face and Kitano's stoic companionship to convey depths of feeling.

Then, the violence arrives. It’s swift, brutal, and utterly unsentimental, often occurring just off-screen or depicted with a shocking bluntness that catches you off guard. There's no glorification here, just the grim reality of consequence. This contrast is jarring, yet essential. It reflects Nishi's own divided nature and perhaps Kitano's view of existence itself – moments of grace punctuated by inevitable suffering. The legendary Joe Hisaishi, frequent collaborator with Studio Ghibli, provides a score that perfectly mirrors this duality – melancholic, hauntingly beautiful, yet capable of underscoring moments of tension with chilling restraint.

### Behind the Somber Canvas

Hana-bi wasn't an easy sell initially, especially in Japan where Kitano was primarily known as the comedian "Beat Takeshi." However, its triumph at the 1997 Venice Film Festival, where it won the prestigious Golden Lion, cemented Kitano's status as a major international filmmaker. Made for a relatively modest budget (reportedly around $3 million USD), its critical acclaim far outweighed its initial box office performance, proving pivotal for Kitano's directorial path, allowing him to continue making unique, personal films like Kikujiro (1999). The film's deliberate pacing and challenging themes might have bewildered some audiences accustomed to more conventional fare, but for those willing to meet it on its own terms, the rewards were immense. It’s a film that doesn’t offer easy answers, leaving you instead with lingering questions about morality, sacrifice, and the meaning found in shared silence.

The way Kitano integrated his own paintings wasn't just a gimmick; it was a narrative lifeline for Horibe, a visual representation of finding a new way to exist after trauma. Seeing those uniquely styled artworks, born from Kitano's own recovery, adds an almost documentary layer to Horibe's struggle and eventual, quiet acceptance.

### Lingering Embers

What stays with you long after the credits roll on Hana-bi? For me, it’s the quiet moments between Nishi and Miyuki, the weight of unspoken love against the backdrop of impending loss. It's the haunting beauty of Hisaishi's score, and the stark, unforgettable imagery – a snow-covered landscape, a child's kite, the sudden flash of violence. Does Nishi achieve a form of peace, or is his final act one of ultimate resignation? The film refuses to judge, leaving the viewer to contemplate the complex tapestry of his motivations. It’s a challenging film, undoubtedly, but one whose emotional power remains undiminished. It feels less like a movie watched and more like an experience absorbed, settling deep within you.

Rating: 9/10

Justification: Hana-bi earns this high score for its masterful direction, achieving a unique and powerful tone that blends stark violence with profound tenderness. Kitano's minimalist performance is iconic, and the supporting cast, particularly Kishimoto, is exceptional. The integration of Kitano's personal experiences and artwork adds layers of meaning, elevated further by Hisaishi's unforgettable score. While its deliberate pace and bleakness might not be for everyone, its artistry, emotional depth, and lasting impact make it a landmark of 90s cinema.

Final Thought: A film that truly embodies the "art" in art-house crime cinema, Hana-bi remains a potent reminder that sometimes the quietest films leave the loudest echoes.