It’s a strange sensation, isn’t it? When a film, seemingly ripped from the cynical headlines of tomorrow, lands on your VCR screen with the immediacy of breaking news. Watching Barry Levinson’s Wag the Dog back in 1997 felt less like settling in for a movie and more like accidentally intercepting a classified briefing. There was an unnerving buzz around this one, a feeling that it was cutting closer to the bone than most political satires dared. Pulling that tape from its sleeve, you almost felt complicit in the darkly comic conspiracy it was about to unveil.

### Truth is Just Another Product

The premise is audacious, almost farcical, yet delivered with chilling plausibility. Mere weeks before a presidential election, the incumbent is embroiled in a sex scandal involving an underage girl in the Oval Office. Enter Conrad Brean (Robert De Niro), a shadowy political fixer, a maestro of manipulation whose job isn't to solve the problem, but to change the story. His solution? Hire Hollywood producer extraordinaire Stanley Motss (Dustin Hoffman) to literally produce a fake war with Albania, complete with stirring theme songs, manufactured heroes, and heart-wrenching archival footage—all created on a soundstage. It’s a concept so outlandish it forces a laugh, followed immediately by the uncomfortable question: could this actually happen?

### De Niro & Hoffman: Masters of Spin

What elevates Wag the Dog beyond its clever concept is the electrifying dynamic between its leads. De Niro, fresh off intense roles like in Heat (1995), plays Brean with a terrifyingly calm pragmatism. He’s the ultimate operator, viewing catastrophic events merely as PR challenges. There’s no malice in his eyes, just the unwavering focus of a man entirely detached from moral consequence. His quiet confidence is the bedrock upon which the film’s absurdity is built.

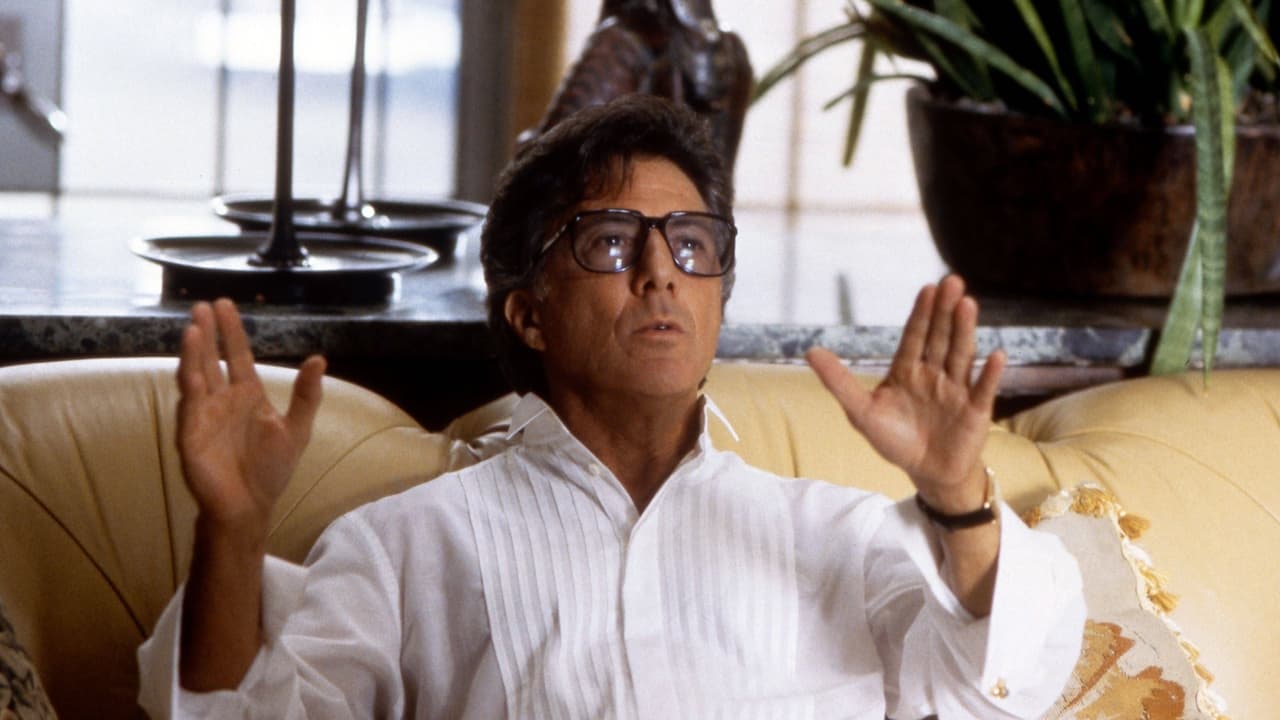

Then there’s Dustin Hoffman as Stanley Motss, a whirlwind of ego, insecurity, and creative genius. It’s a performance humming with neurotic energy, a portrait of a man utterly consumed by the artifice he creates. Hoffman reportedly modeled Motss on legendary producer Robert Evans (Chinatown, The Godfather), even studying Evans' cadence and mannerisms from his audiobook memoir, The Kid Stays in the Picture. The result is unforgettable – Motss isn't just faking a war; he's crafting his masterpiece, desperate for the recognition he feels Hollywood has denied him ("It's the best work I've ever done!"). The tragedy, of course, is that he can never take credit. Supporting them perfectly is Anne Heche as Winifred Ames, the increasingly frazzled White House aide caught between Brean’s chilling efficiency and Motss’s theatrical demands, her performance grounding the escalating insanity.

### Art Imitating... Imminent Reality?

The film’s production itself had a lightning-fast quality, shot in just 29 days, mirroring the frantic pace of the spin operation depicted on screen. This rapid turnaround contributed to its raw, almost documentary-like feel in places, despite the Hollywood sheen provided by Motss's sequences. And then, the truly uncanny happened. Mere weeks after Wag the Dog's release in December 1997, the Monica Lewinsky scandal broke, engulfing the Clinton presidency. Suddenly, Levinson's film wasn't just satire; it felt terrifyingly prescient. Life hadn't just imitated art; it seemed to be following its script. Did reality take a cue, or did the film simply tap into a political reality already operating just beneath the surface? That question hung heavy in the air during subsequent viewings, lending the film an eerie weight it retains to this day.

The mechanics of the deception are laid bare with cynical glee. We see the creation of the war song ("Good Old Shoe," penned for the film by the legendary Willie Nelson), the casting of a supposed forgotten hero (a manic cameo by Woody Harrelson as Sgt. Schumann), and the digital manipulation of footage featuring a young Albanian girl (played by a then-unknown Kirsten Dunst) fleeing manufactured terror, clutching a bag of Tostitos because that's what was handy on set. It's horrifyingly funny, showcasing how easily narratives can be constructed and sold to a compliant media and a distracted public.

### Mamet's Razor Edge

The script, co-written by Hilary Henkin and the legendary playwright David Mamet (based on Larry Beinhart's novel American Hero), crackles with Mamet's signature sharp, cynical dialogue. Lines land like punches, exposing the hollow language of politics and media spin. Levinson, who previously directed Hoffman to an Oscar in Rain Man (1988) and navigated political themes in Good Morning, Vietnam (1987), keeps the pacing taut and the tone perfectly balanced between dark comedy and unsettling realism. The film never winks too hard; it presents its absurd scenario with a straight face, letting the horror dawn on the viewer gradually.

### Beyond the Smoke and Mirrors

Watching Wag the Dog today, long after the VHS tapes have warped and the specific scandals that birthed it have faded into history books, its power hasn't diminished. If anything, in our current era saturated with "fake news," alternative facts, and sophisticated digital manipulation, the film feels less like prophecy and more like a documentary exposé. It holds up a mirror not just to political machinations, but to our own consumption of media. How much of what we see is real? How much is produced, packaged, and sold? The film doesn’t offer easy answers, but it forces us to ask the questions.

Rating: 9/10

Wag the Dog is a masterful piece of political satire, brilliantly acted, sharply written, and chillingly relevant. The central performances by Hoffman and De Niro are superb, driving the narrative with their contrasting energies. Its uncanny timing with real-world events cemented its legacy, but its exploration of media manipulation and the manufacturing of reality ensures its enduring power. It's a film that was vital viewing on its initial VHS release and remains essential viewing today. It leaves you chuckling darkly, but also deeply unsettled, pondering the thin line between the newsroom and the soundstage. What's scarier: the lie itself, or how easily we might believe it?