It arrives like a mirage shimmering in the desert heat – the promise of progress, of order, dangled before the desperate. But in Luis Estrada’s searing 1999 political satire, Herod's Law (La Ley de Herodes), that mirage quickly dissolves into the dust and decay of San Pedro de los Saguaros, revealing the brutal mechanisms of power that grind hope into cynical resignation. This isn't a gentle stroll down memory lane; it's a barbed, often bitterly funny, plunge into the heart of institutional rot, a film whose late-90s arrival felt like a Molotov cocktail lobbed at the Mexican political establishment.

A Dusty Road to Power

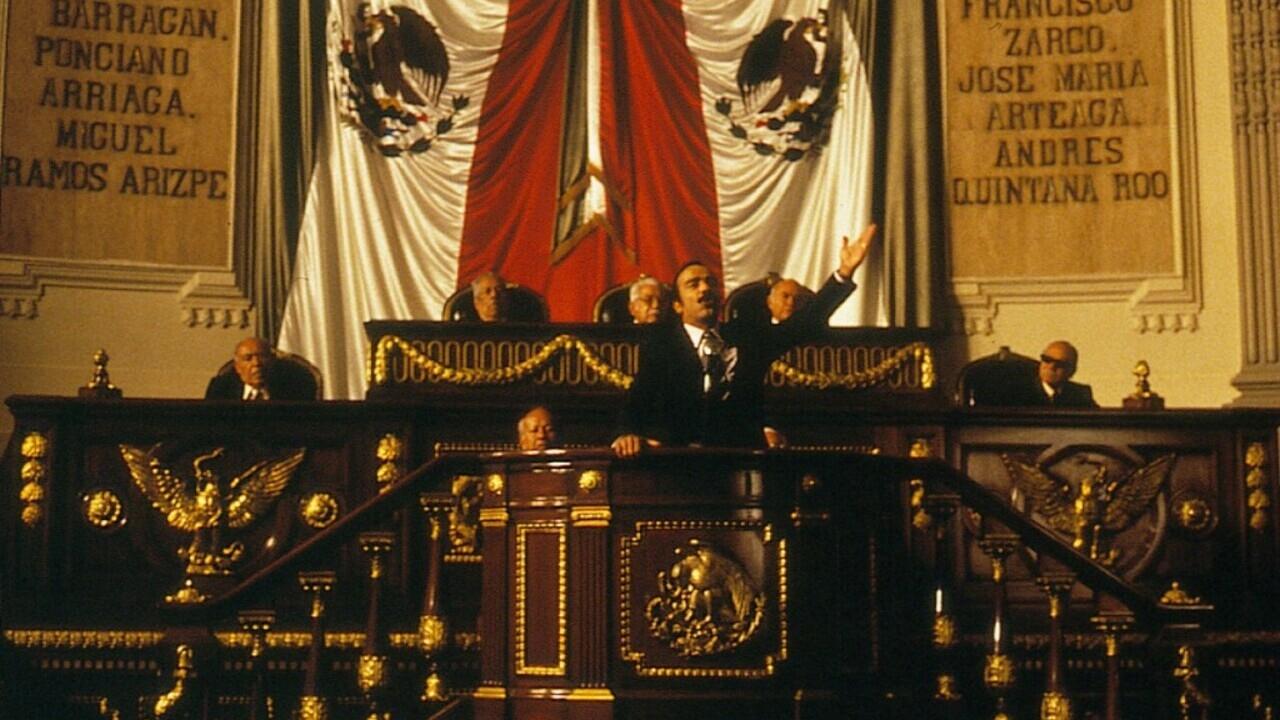

Set in 1949, during the seemingly unshakeable reign of Mexico's Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), the film introduces us to Juan Vargas (Damián Alcázar), a lowly dump caretaker and earnest party loyalist. When the mayor of the remote indigenous town of San Pedro is unceremoniously lynched by his constituents (a grimly effective opening), the party brass needs a temporary stooge. Enter Vargas, armed with little more than blind faith in the party, a copy of the Constitution, and a pistol he barely knows how to use. He arrives in San Pedro, a town forgotten by time and starved by neglect, genuinely intending to bring modernization and justice. We see the idealism flicker in his eyes, the belief that he can make a difference. Remember that feeling? The conviction that good intentions are enough?

The School of Hard Knocks, PRI-Style

Vargas's optimism doesn't stand a chance. San Pedro is a microcosm of systemic failure. There's the venal local priest, the shrewd brothel madam, and the ever-present shadow of Secretary López (Pedro Armendáriz Jr., radiating cynical authority), the party man who delivers the film's central, brutal philosophy: "La Ley de Herodes – o te chingas o te jodes." Roughly translated, it's the law of Herod: screw others over, or get screwed over yourself. It's a lesson Vargas learns with terrifying speed. Armendáriz Jr., son of the Golden Age Mexican cinema icon, embodies the weary, entrenched corruption that sees idealism as merely a temporary inconvenience. His performance is a masterclass in understated menace, the weary teacher initiating his pupil into the true ways of the world.

Alcázar's Chilling Descent

The film pivots on the transformation of Juan Vargas, and Damián Alcázar delivers a career-defining performance. His journey from wide-eyed naif to ruthless strongman is utterly convincing, and deeply unsettling. We watch as the desire to do good curdles into a hunger for power, as extortion replaces taxation, and as the Constitution becomes a tool for oppression rather than justice. Alcázar doesn't just play a man corrupted; he inhabits the skin of someone discovering a terrifying aptitude for tyranny, his initial awkwardness hardening into calculated cruelty. It’s a chilling reminder of how easily power can warp even the seemingly meekest soul. What does it say about human nature that this descent feels so horribly plausible?

More Than Just a Satire

While often darkly humorous, Herod's Law pulls no punches. Estrada, who would continue his scathing critiques of Mexican society with films like El Infierno (2010) and The Perfect Dictatorship (2014), uses the 1949 setting to comment directly on the decades of PRI rule. The poverty, the exploitation of indigenous communities, the casual violence, the impunity enjoyed by those in power – it's all laid bare. The fictional San Pedro de los Saguaros, filmed with stark realism in the desolate landscapes of Zapotitlán Salinas, Puebla, becomes a powerful symbol of a nation held captive by its own political machinery. Doesn't that feeling of systemic inertia, of the "way things are," resonate far beyond its specific setting?

A Film They Tried to Bury

Here’s where the story gets truly fascinating, a real-life echo of the film's themes. Herod's Law was ironically co-produced by the Mexican state film institute, IMCINE. Upon seeing the finished product – a blistering indictment of the ruling PRI released just months before the historic 2000 election that would end their 71-year grip on power – officials panicked. They attempted to bury the film, initially giving it only a handful of screens and trying to restrict its distribution. It’s a classic case of art imitating life imitating art. However, word got out, fueled by critical praise and public curiosity. The attempted censorship backfired spectacularly, turning Herod's Law into a cause célèbre and a massive box office success in Mexico. People needed to see the film the government didn't want them to see. It became more than just a movie; it became an event, a conversation starter, a cathartic roar against the status quo. Imagine the buzz around that video rental back in the day!

Echoes in the Dust

Watching Herod's Law today, even on a well-worn tape or an early DVD pressing, its power hasn't diminished. Estrada’s direction is assured, capturing both the bleak absurdity and the quiet tragedies unfolding in San Pedro. The film’s look is gritty, almost documentary-like at times, grounding the satire in a tangible reality. It’s a potent piece of late-90s cinema that might have bypassed some international audiences focused on Hollywood blockbusters, but its insights into corruption, power, and human fallibility feel timeless and universal. It reminds us that the mechanisms of oppression often wear the mask of progress.

---

Rating: 9/10

Herod's Law earns this high score for its fearless political commentary, Damián Alcázar's towering performance, its perfectly calibrated blend of dark humor and bleak tragedy, and its undeniable historical significance. The script is sharp, the direction unflinching, and the central message remains chillingly relevant. The controversy surrounding its release only adds to its legacy as a film that truly spoke truth to power, forcing a reckoning few saw coming.

It leaves you pondering not just the specific historical context, but the enduring, seductive nature of absolute power itself. A must-see for anyone interested in powerful political cinema, and a stark reminder from the cusp of the millennium that sometimes, the most potent stories are the ones someone tried to silence.