How often does a film leave you feeling not entertained, not thrilled, but genuinely unsettled? Not by jump scares or gore, but by the chillingly recognizable awfulness of human behavior laid bare. Picking up the Neil LaBute-helmed Your Friends & Neighbors from the video store shelf back in 1998 often felt like an act of cinematic bravery, especially if you'd already weathered his devastating debut, In the Company of Men (1997). This wasn't escapism; it felt more like volunteering for emotional reconnaissance behind enemy lines – the enemy being the quiet desperation and casual cruelty lurking beneath the surface of seemingly ordinary relationships.

An Unflinching Look in the Mirror

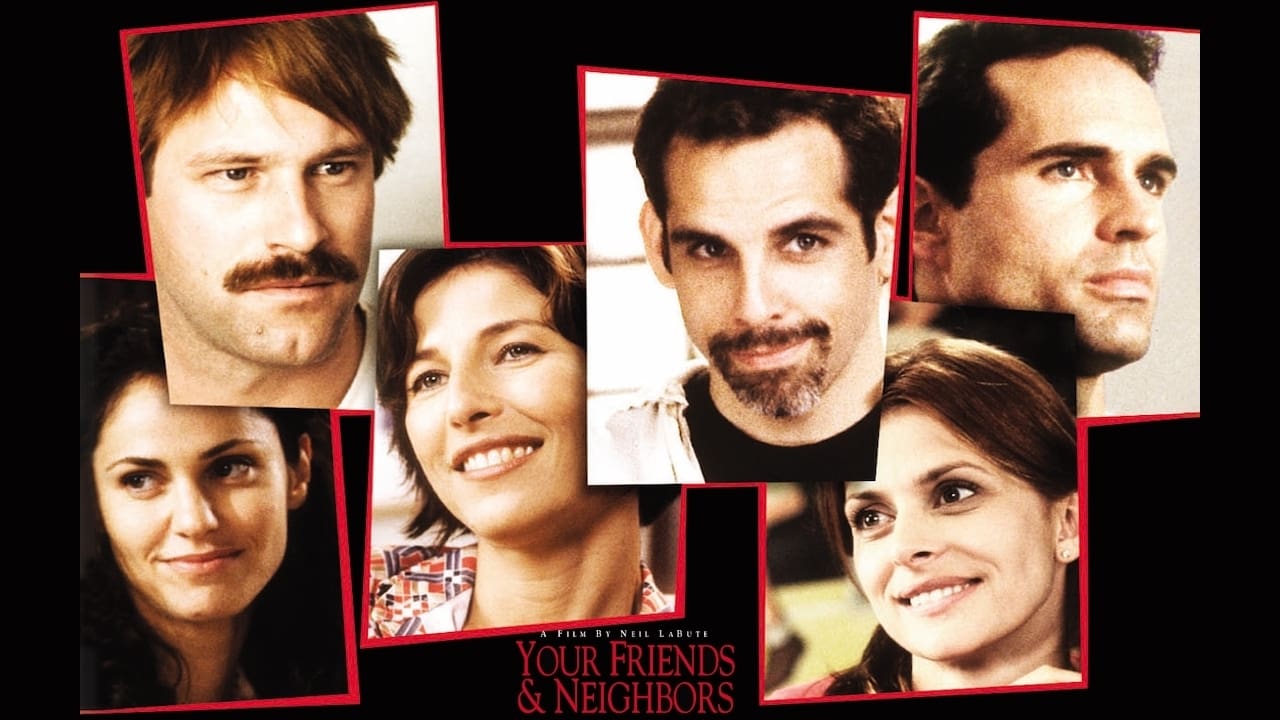

LaBute, pulling double duty as writer and director, crafts a narrative less about plot and more about the toxic interactions between three couples in an unnamed, sterile suburban landscape. There's the seemingly stable Cary (Jason Patric) and Mary (Amy Brenneman), the pretentious theatre director Jerry (Ben Stiller) and his sharp-tongued partner Terri (Catherine Keener), and the boorish but perhaps deceptively honest Barry (Aaron Eckhart, reteaming with LaBute after In the Company of Men) and his equally unsatisfied wife Cheri (Nastassja Kinski). Their lives intertwine through affairs, betrayals, and brutally frank conversations that often feel less like dialogue and more like emotional vivisection. There’s a deliberate chill to the film, amplified by the near-total absence of a non-diegetic musical score – we're left alone with these characters and their often excruciating words.

Performances That Bruise

What makes Your Friends & Neighbors burrow under your skin is the ensemble cast, each committing fully to the ugliness. Aaron Eckhart as Barry is a standout, delivering monologues – particularly one infamous locker-room confession about the "best sex he ever had" – with a kind of unvarnished, almost oblivious narcissism that's both horrifying and strangely magnetic. It’s a performance that dares you to look away but somehow keeps you pinned. Catherine Keener, already a master of conveying intellect laced with simmering discontent, is perfectly cast as Terri. Her scenes with Ben Stiller, playing remarkably against his usual comedic type as the insecure and artistically frustrated Jerry, crackle with a passive-aggression so thick you could spread it. Stiller’s Jerry isn't funny; he's pathetic and unpleasant, a testament to his willingness to explore darker territory. Amy Brenneman’s Mary navigates her dissolving marriage and a tentative lesbian affair with a quiet vulnerability that provides one of the few sparks of genuine, albeit wounded, humanity. And Jason Patric’s Cary remains perhaps the most chillingly enigmatic, a sociopath hiding in plain sight, whose detachment is arguably the most disturbing trait on display.

The LaBute Signature

LaBute’s direction is as stark and unforgiving as his script. The production design emphasizes bland, impersonal spaces – apartments, restaurants, steam rooms – reflecting the emotional emptiness of the characters inhabiting them. The camera often holds steady, forcing us to confront the discomfort head-on. It’s a style that denies easy catharsis or resolution. Reportedly, LaBute's commitment to this bleak vision was absolute; he sought to explore the terrain of modern relationships with unflinching honesty, even if that honesty proved deeply uncomfortable for audiences. It's said the actors found the material challenging but were drawn to its raw power. Watching it again now, it feels like a quintessential late-90s independent film – provocative, dialogue-driven, and utterly uninterested in providing comfort.

Behind the Bleakness: Retro Fun Facts

- That infamous monologue delivered by Aaron Eckhart? LaBute has mentioned it was inspired by real conversations he'd overheard, amplifying the unsettling feeling that this isn't pure fiction, but heightened reality.

- The film cost a relatively modest $5 million to make. While not a massive box office hit (grossing around $4.7 million domestically), its critical reception was strong, solidifying LaBute's reputation as a distinctive, albeit polarizing, voice in American cinema. Initial reactions often centered on its bleakness, with some critics finding it powerful and others finding it gratuitously misanthropic.

- The casting of Ben Stiller was a deliberate move against type. Known primarily for comedies like There's Something About Mary (released the same year!), his portrayal of the insecure and cruel Jerry showcased a different, darker range.

- The deliberate lack of a score wasn't just an aesthetic choice; it forces the audience to focus entirely on the dialogue and the awkward silences, making the uncomfortable moments feel even more pronounced. Any music heard is diegetic – playing within the scene itself.

Lingering Discomfort

Your Friends & Neighbors isn't a film you "enjoy" in the traditional sense. It doesn't offer heroes to root for or satisfying arcs of redemption. Instead, it presents a series of meticulously crafted character studies steeped in betrayal, narcissism, and profound miscommunication. Does it accurately reflect all relationships? Of course not. But does it tap into truths about insecurity, ego, and the ways people hurt each other, often unintentionally, sometimes with chilling calculation? Absolutely. It asks uncomfortable questions: How well do we truly know the people closest to us? What selfish impulses drive our actions, even when we pretend otherwise?

Revisiting it on VHS (or whatever format you find it on now) is a reminder of a time when mainstream-adjacent cinema could still deliver something this bracingly sour, this willing to alienate its audience in pursuit of a difficult truth. It’s a conversation piece, a relationship horror film disguised as a drama, and a potent example of LaBute's singular, unsettling vision.

Rating: 7.5/10

Justification: The film is impeccably crafted, brilliantly acted, and achieves its intended effect with unnerving precision. LaBute's writing is sharp, albeit relentlessly bleak. The performances, particularly from Eckhart, Keener, and Stiller (playing against type), are exceptional. It loses points primarily because its unrelenting cynicism and lack of any redeeming qualities make it a demanding, often unpleasant watch that lacks the nuance or glimmers of hope found in some other explorations of dark human nature. It's powerful, but difficult to truly embrace.

Final Thought: This is one tape from the back shelf that doesn't offer warm nostalgia, but rather a cold, hard look at the darkness people are capable of – a reminder that sometimes the most monstrous things aren't supernatural, but terrifyingly human.