### The Chill You Can't Shake

Some films settle over you like a fine dust, barely noticeable until the light hits just right. Others arrive like a sudden drop in temperature, a palpable chill that lingers long after the credits roll. Neil LaBute's 1997 debut, In the Company of Men, belongs firmly in the latter category. Watching it again now, decades after first sliding that stark white VHS tape into the machine – likely found tucked away in the 'Independent' or 'Drama' section of the local video store, far from the colourful blockbuster displays – the discomfort remains remarkably potent. It’s not an easy watch; it wasn’t meant to be. But it forces a confrontation with workplace toxicity and casual cruelty in a way few films dared to then, or perhaps even now.

### A Poisoned Pact

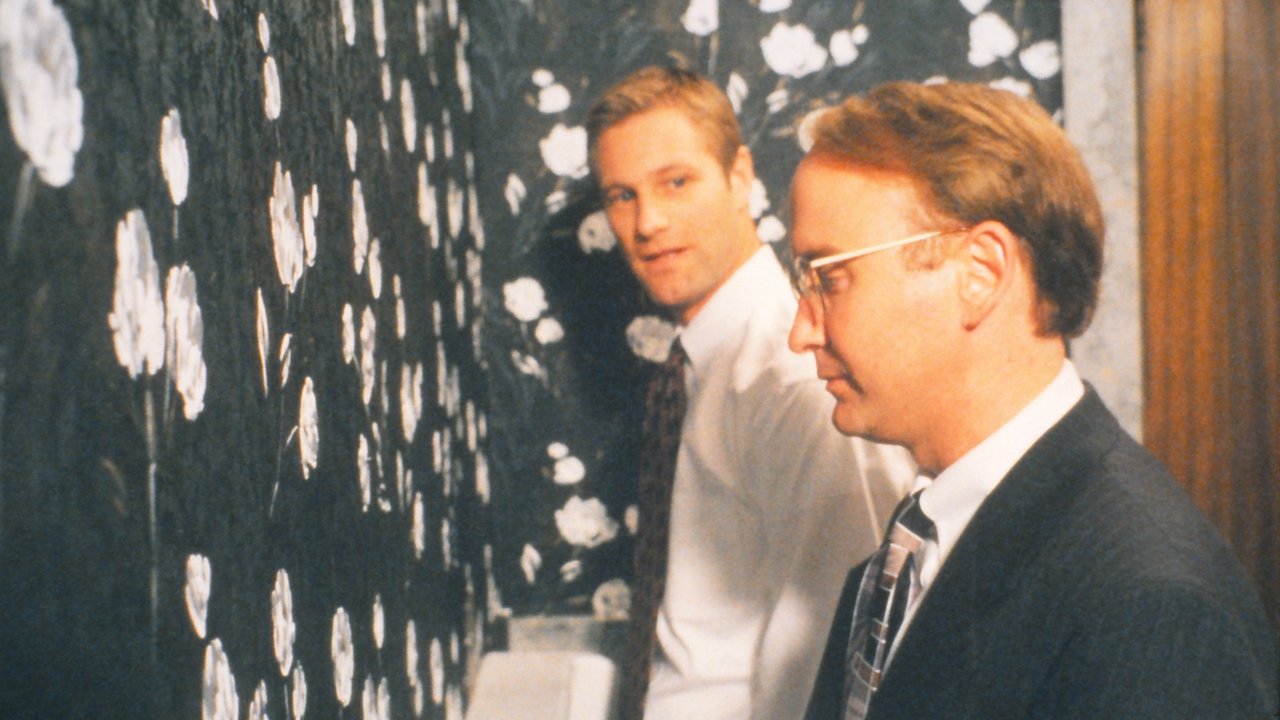

The premise is deceptively simple, yet monstrous. Two mid-level corporate executives, Chad (Aaron Eckhart in a star-making, utterly chilling performance) and Howard (Matt Malloy), are dispatched to a regional office for a six-week project. Both men are smarting from recent romantic rejections. Nursing their wounded egos, the charismatic but deeply misogynistic Chad concocts a plan: they will find a vulnerable woman, both romance her simultaneously, build her up, and then savagely discard her. Just because they can. Howard, initially hesitant but ultimately weak-willed and easily led, agrees. Their target becomes Christine (Stacy Edwards), a deaf typist in the office whose disability, in Chad's venomous worldview, makes her the perfect victim – someone seemingly unable to fully "hear" their lies.

What unfolds is less a traditional narrative and more a slow, meticulous dissection of malice. LaBute, adapting his own stage play, traps us within sterile office environments, bland hotel rooms, and anonymous airport lounges – spaces that reflect the emotional emptiness of the central characters. There's a deliberate, almost theatrical staging to many scenes, emphasizing the performative nature of Chad's cruelty and Howard's complicity. It feels claustrophobic, inescapable. You become an unwilling observer, stuck in the room as the ugliness unfolds.

### Performances That Cut Deep

The film rests entirely on its three central performances, and they are uniformly exceptional. Aaron Eckhart, previously a relative unknown, is a revelation. He embodies Chad with a terrifying blend of surface charm and utter soullessness. It's not just overt aggression; it's the smug confidence, the manipulative language, the way he weaponizes corporate jargon and casual sexism. There’s a disturbing lack of empathy that feels chillingly authentic. It’s a performance that announced a major talent, even if it was one that likely made audiences recoil. Remember seeing Erin Brockovich (2000) a few years later and thinking, "Wait, that's the nice biker guy? From that movie?" It speaks volumes about Eckhart's range.

Matt Malloy as Howard is equally crucial. He represents the banality of evil – the "good guy" who stands by and does nothing, swayed by peer pressure and his own simmering resentments. His passivity is infuriating, yet depressingly recognizable. How many Howards have we encountered, unwilling to rock the boat even when witnessing blatant wrongdoing? His internal conflict, barely visible beneath a veneer of corporate dronehood, makes the eventual outcome even more devastating.

And then there's Stacy Edwards as Christine. She navigates a difficult role with immense grace and intelligence. Christine is not merely a symbol or a passive victim. Edwards imbues her with warmth, hope, and a quiet strength. Her deafness isn't portrayed as a weakness to be exploited, but simply a part of who she is. The moments where she begins to trust, to open up, are rendered with such sensitivity that the inevitable betrayal feels like a physical blow. Her performance ensures the film retains its humanity, preventing it from becoming purely an exercise in nihilism.

### From Stage to Screen on a Shoestring

Understanding the film's origins adds another layer. LaBute penned the play while working at Brigham Young University, and its unflinching look at misogyny reportedly stirred controversy even then. The transition to film was achieved on a minuscule budget – reportedly around $25,000, a figure almost unbelievable for the quality achieved. Shot in just 11 days primarily in Fort Wayne, Indiana, the production constraints likely contributed to its stark, minimalist aesthetic. There are no flashy camera moves, no elaborate sets – just raw dialogue and powerhouse acting.

When In the Company of Men premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, it caused a significant stir, winning the Filmmakers Trophy and securing distribution. It was a challenging, confrontational piece arriving amidst the often slicker, more optimistic mainstream cinema of the late 90s. Finding this on VHS felt like discovering something illicit, something sharp-edged and dangerous that had somehow slipped through the cracks. It wasn't escapism; it was an indictment.

### Lasting Discomfort

In the Company of Men isn't a film you "enjoy" in the traditional sense. It's a film that gets under your skin, that makes you examine the dynamics of power, gender, and complicity in everyday interactions. It raises uncomfortable questions: Why does Howard go along with it? What allows Chad's toxicity to flourish? How often does this kind of casual cruelty occur, unseen and unremarked upon? Its power lies in its refusal to offer easy answers or catharsis. The bleakness is the point.

Watching it today, its themes feel depressingly relevant. While the specific corporate environment might look dated (no smartphones, lots of beige!), the underlying currents of misogyny, insecurity masked as bravado, and the corrosive effects of unchecked power dynamics remain potent subjects. It’s a stark reminder that the veneer of civility can often hide profound ugliness.

Rating: 8/10

This rating reflects the film's undeniable power, provocative nature, and exceptional performances, particularly Eckhart's career-defining turn. It's docked slightly simply because its relentless bleakness and confrontational style make it a difficult, rather than pleasurable, viewing experience – though undeniably impactful and masterfully crafted for its budget.

Final Thought: A brutal, necessary artifact of 90s independent cinema, In the Company of Men is the kind of film that, once seen, is impossible to forget – lodging itself in your mind like a shard of ice. It's a chilling examination of the darkness that can fester behind the forced smiles and polite handshakes of the corporate world.